Fort Jackson, S.C. -- On a recent Wednesday afternoon at the Main Post Chapel, about a dozen golden and black Labrador Retrievers sat calmly on the basement floor. The dogs only occasionally looked up as a human volunteer put peanut butter and jelly onto a loaf of bread without opening the jars.

In the middle of a group of about 10 Soldiers, one of them, his chair turned opposite the rest of the group -- attempted to coach the volunteer through making a peanut butter and jelly sandwich.

The strange exercise was just one aimed at showing a small group of Soldiers the communication challenges dogs experience when working with people.

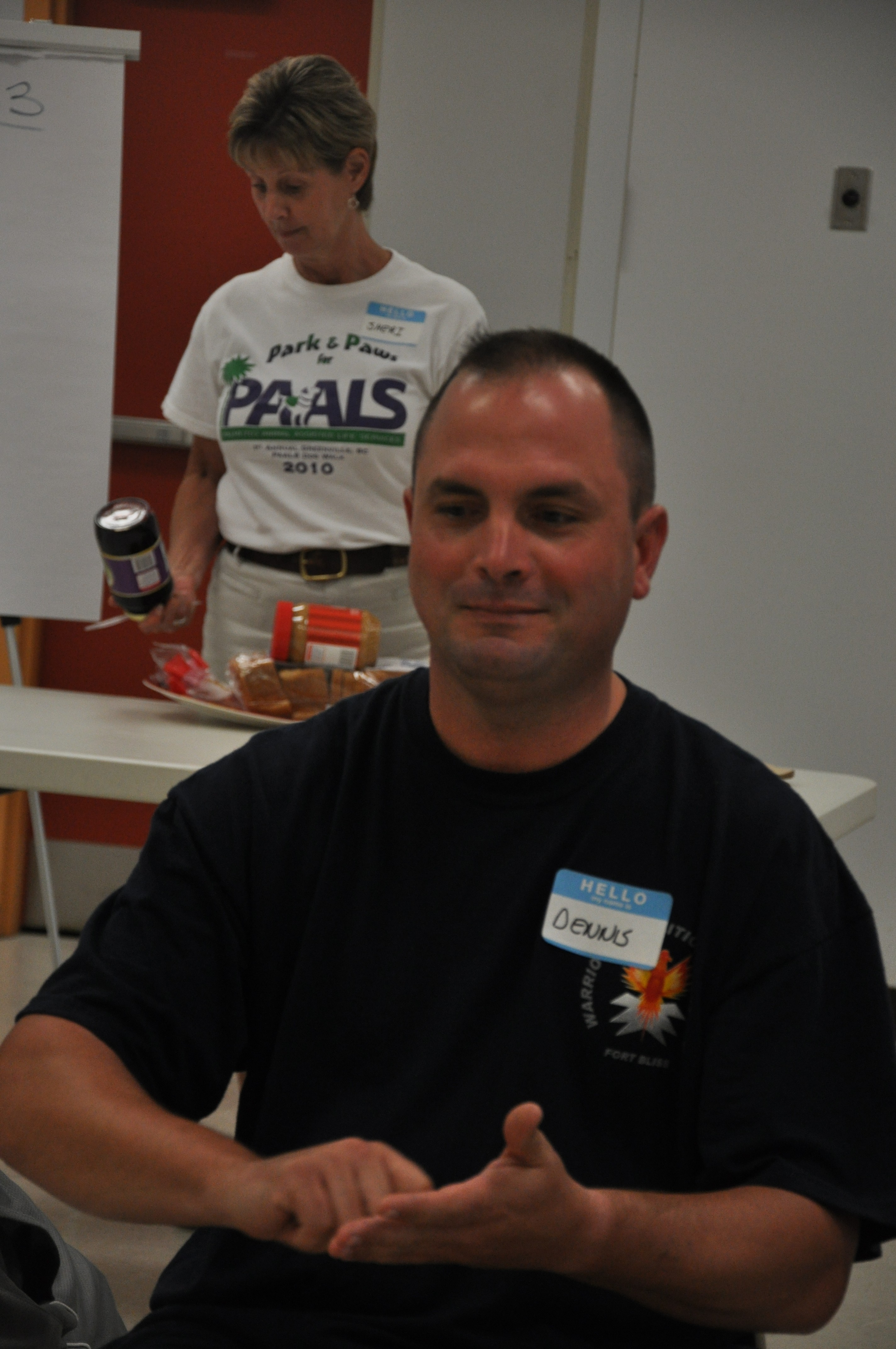

The Soldiers and volunteers are part of an eight-week pilot program with Palmetto Animal Assistance Life Services -- or PAALS -- which enables Soldiers suffering from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder to train dogs that will go on to become assistance dogs for someone else.

Jennifer Rogers, executive director of PAALS, said the idea originally came from an out-of-state group taking a similar approach. "One of PAALS’s goals has always been training dogs to use with those in the community," she said. The group began receiving calls from those requesting dogs. Although the supply could not keep up with demand, Rogers knew there was something the group could do to help veterans suffering from PTSD or other anxiety disorders.

"By golly, we ought to be doing something for the (men and women) who come back and need something," she said.

The solution was to take dogs of various ages and stages of training "the dogs range from 7 months to 4 years" and have a group of Soldiers help train them. It takes about two years for each dog to be completely trained and ready to go into service. Rogers said a previous experience with a service member who was afraid to leave his home showed her that such a program could really benefit someone with PTSD.

"He was so young; he had small kids and a wife (but) he really wasn’t functioning," she said.

After working with the dogs, the service member took a huge step by going to a crowded area with the dog, something he had not done in months.

"I saw firsthand how the dogs help," Rogers said.

Although the program is not a form of therapy, it is a result of research that shows that people who are around dogs tend to be calmer and some of their health ailments seem to be eased.

"We know that having interaction with animals is beneficial," said Dr. Alison Thirkield, a psychologist with Moncrief Army Community Hospital’s Joint Behavioral Health Services who volunteers with PAALS.

During the eight-week program, Soldiers go through drills with the dogs, teaching them everything from "stay" to having them walk, undistracted, in a circle. Thirkield said that she hopes the program is beneficial to both the dogs and the Soldiers.

"By working with the Soldier, we will know what behaviors (the dogs) need if they go to a Soldier," she said. As for the Soldiers, they are learning a lot about how behaviors are learned, which ... can teach them about themselves and other people, she said.

"I’m hoping they can take what they’ve learned with the dogs and get insight into themselves."

PTSD sufferers often have difficulty forming relationships, being in groups and interacting with strangers. Those who participate in the program do all three, but having a specific purpose" training the dogs" somehow makes the situation more palatable, Rogers said.

"One of the things the dogs do is (help the Soldiers) take the focus off themselves," she said. "It helps them overcome some of the initial problems, like being in a group."

Staff Sgt. Jayson Arnote, with the 3rd Battalion, 13th Infantry Regiment, said he has already seen a change in himself since beginning the program. The biggest, he said, is how he remains patient "and doesn’t get visibly aggravated" when the dogs do not immediately follow a command or become unruly.

"The biggest thing is I (don’t) snap like I would have in the past, so something has to be working," he said. "Being an infantryman, I have control over ... how I take care of (a certain) situation. In this ... I don’t have that control. We’re teaching (the dogs) and they’re teaching us. With them, I’ve really had to slow down."

Arnote said that is a far cry from the Soldier he was just a few months ago.

A 13-year veteran, Arnote has gone through two deployments, and said he suffered from some of the usual symptoms of PTSD; irritability, anxiety, anger, insomnia and nightmares.

"You’re always on guard. Little things always bother you," he said.

A turning point for him came when he was assigned to Fort Jackson as a drill sergeant; he said he got into trouble and was taken off the trail. After several months of inpatient treatment for his PTSD, he was encouraged to participate in the PAALS program, which "along with a supportive command team" he said has helped him transition.

"Once you get out into the real world, it’s a whole other story. It’s very challenging; very difficult at times."

Participating in the program also gives him a sense of duty as he helps to train dogs that will be used to help someone else, something that Rogers and Thirkield say is important.

"One of the most rewarding things to them is helping other people," Thirkield said of the Soldier-volunteers.

The training also helps the dogs by allowing them to be around various people and personalities, which can help volunteers when it is time to place the dog. For example, Rogers said, a dog that tended to be headstrong and rambunctious may not be a good fit for someone with PTSD. Rogers said that the changes Arnote said he has undergone have not gone unnoticed.

"It’s been really rewarding for us," she said. "Very quickly, we’ve seen how quickly the guys changed. I think it’s been powerful."

Arnote knows firsthand the type of friendship a dog provides. His dog, Buddy, who was found on the side of the road, is now “the light of my life.”

"With a dog, he doesn’t know anything about my story or my background," Arnote said. And that is the type of feeling he wants to help provide someone else.

"Knowing that these dogs can possibly make their lives a little bit easier makes me feel good," he said. "That’s what makes me show up each Wednesday. It’s a good deal."

Social Sharing