Editors note: Portions of this story have been excerpted with permission from "Surviving the Folded Flag: Parents of war share stories of coping, courage, and faith," by Deborah H. Tainsh, a Gold Star Mother. For Tainsh's story, see the

May 2008 issue of Soldiers, available online at www.army.mil/soldiers/archives.

HUMANS have marked their bodies with tattoos for more than 5,000 years, from the famous Iceman who was carbon-dated at around 5,200 years old, to royal Egyptian women, and Soldiers fighting in the trenches of Fallujah, Baghdad and Kabul.

Over the past millennium, these permanent, very personal designs, have served as amulets, status symbols, declarations of love, signs of religious beliefs, adornments and even forms of punishment.

But for today's Soldiers and Families, a tattoo has become a statement to the world that someone close to them has fallen, whether a comrade, father, husband, son or daughter.

Donna Engeman, currently the Survivor Outreach Services program manager at the Army's Family and Morale, Welfare and Recreation Command, Fort Sam Houston, Texas, lost her husband Chief Warrant Officer John Engeman in Iraq, May 2006.

"For me the 'inking' began about three years ago when I was going through airport security during a trip for work. There was a Soldier in uniform going through the line in front of me and the security guard thanked him profusely for his service, which was certainly very appropriate. Yet, when I went through the line, proudly wearing my tiny little Gold Star pin, there was not a word of acknowledgement for my husband's service and sacrifice," Engeman said.

Donna knows she doesn't have any outward signs of her loss-she hasn't lost a limb or other body part, she says. "My heart, though, was absolutely shattered and virtually ripped out, but it continues to beat as I live on without him. I don't know if there's a strong enough word to describe how important it is to me that our nation know and remember John's sacrifice-such a good and honorable man who lived and died for our nation and our freedom. No matter where I go or what I do from here, I will always, always make sure he is remembered. It is the very least I can do for him," Engeman said.

While struggling to figure a way to keep his memory alive, she decided on a tattoo. It would not get lost or fall apart in the laundry as some pins do, and it is permanent.

"I chose to have the Gold Star pin put over a heart to symbolize my shattered heart and the pin from a grateful nation, and I wanted his dog tags and chain wrapped around it all to illustrate his devotion to duty. But I wanted the circular chain broken to symbolize that only death would separate us. And I chose to put it on my left shoulder because it is closest to my heart," she said.

His skin-deep inking of the body First gained acceptability in mainstream culture because of the military.

During World War II, tattooing came to be seen as the sign of a tough guy, or "man of the world," when Soldiers, Sailors and Marines traveled the world, making contact with cultures that practiced the art form. Being willing to fight and die for one's country is very noble, so tattoos gained a bit of credibility.

Today, it's not uncommon to see suburban housewives, lawyers and accountants getting ink-not at the tattoo parlor that glorifies the urban outlaw-but at the tattoo art studio that features custom, fine-art designs, as seen on TV shows like "Miami Ink" and "LA Ink."

With tattooing riding a wave of popularity within the 17- to 24-year-old age group, the rising tide of ink for male and female tattoo enthusiasts is quickly flooding the military service recruitment pool.

According to a Pew Research Center report, of those born after 1980, 31 percent have one tattoo, 50 percent have two to five, and 9 percent have six or more tattoos. But however many they have, most adults don't display them for the entire world to see.

For those in the military or Family members of the armed services, this hidden art is coming out of the shadows.

Captain Patrick J. Engeman, Donna and John's son, who served twice in Iraq after losing his father, decided to wear his tattoo in memory of his dad on his sleeve, so to speak.

"I originally had a KIA bracelet made for my dad, and that is what I used to wear all the time. But the bracelet kept getting scratched up and caught on my gear and was getting in pretty bad shape. I decided I wanted to get a tattoo instead of the bracelet," Engeman said.

His original plan was to essentially have the bracelet tattooed on his wrist "I really liked KIA bracelet and the information on it, so it seemed perfect. I brought my idea to a local parlor that has a really good reputation. I like the artists because they are very good at taking an idea and developing a tattoo from it," Engeman said.

The artist found that the size and detail of the warrant eagle and ordnance crest, the featured elements of the design, required a much larger template.

"When I saw the design he came up with, I knew that's what I wanted. I chose my right forearm because that was where I used to wear the bracelet. I had thought about doing something on my chest over my heart, but I kind of wanted people to be able to see it.

"I really didn't discuss it with any of my family or friends. I had told my mom and sister that I wanted to get one for my dad but wasn't sure what to get. But when I saw the design I knew they would both really like it," Engeman said.

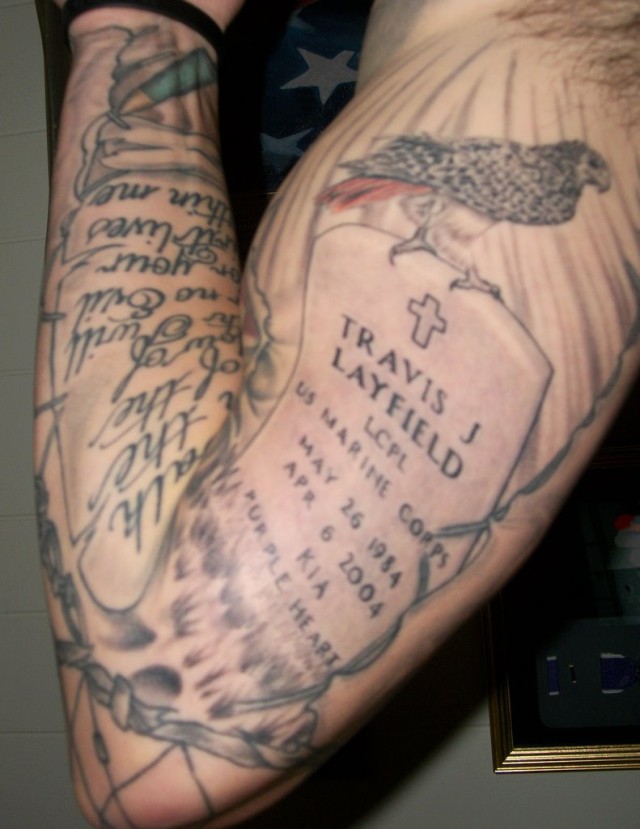

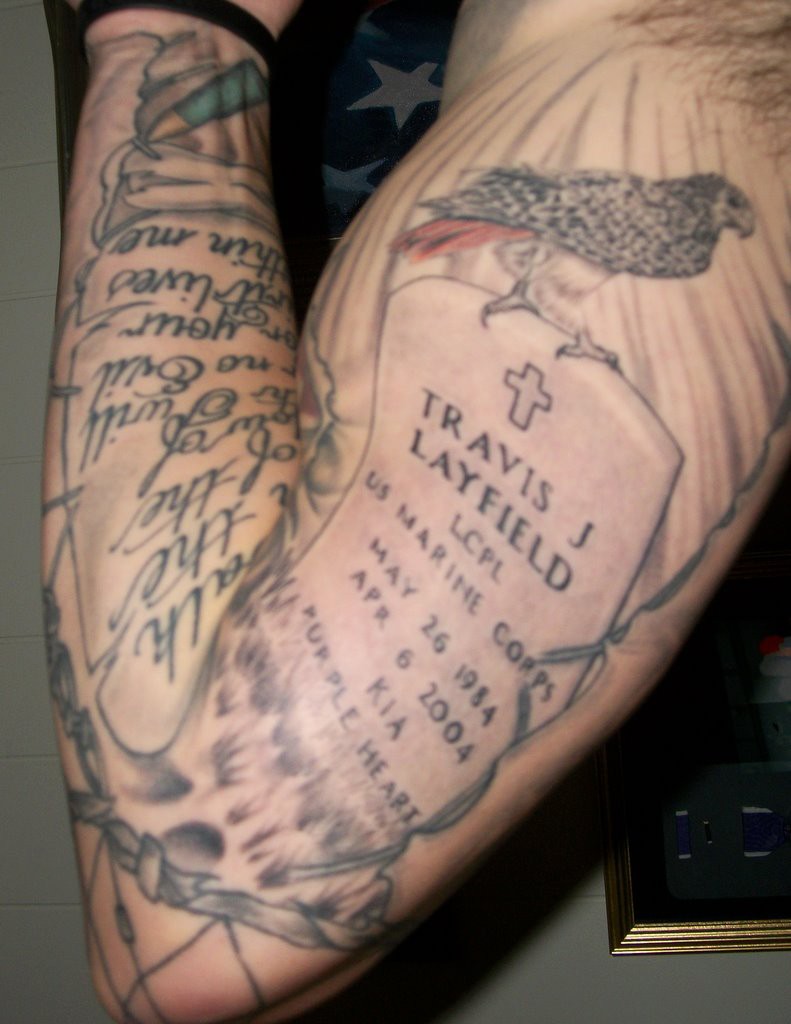

Dianne Layfield still isn't sure about getting a tattoo, although nearly everyone in her family has been inked, including her son, Marine Lance Cpl. Travis Layfield, killed in Anbar Province, Iraq, April 6, 2004.

"Travis had a tribal feather tattoo to represent his Lakota Sioux heritage on his father's side. My son, Tyler, preserved his brother's legacy by getting a feather tattooed on his arm right after we received the news. At Travis's funeral services a Lakota medicine man, who played drums and sang, asked me if I knew what the feather meant. I told him I thought it meant 'first born.' He said, 'No, it means fallen warrior.' I still get chills remembering this. I think Travis must have known," Layfield said.

His brother, Tyler, never wanted a tattoo because he didn't like them, said his mother. But when his grandfather, a Navy Seabee, died, he decided to get the Seabee emblem tattooed on his shoulder. He also got Travis' dog tags tattooed around his neck and then completed a sleeve of tattoos.

"Tyler has been working on this sleeve for so long, but he wanted everything a perfect tribute to his brother," she said.

"Travis' older brother, Todd, who's in Arkansas, got a tattoo of the USMC emblem and the bulldog mascot. And my niece got Travis' feather tattooed on the top of her foot. Now everyone's saying it's my turn to get one in memory of my Travis. I'm not so sure, yet," Layfield said.

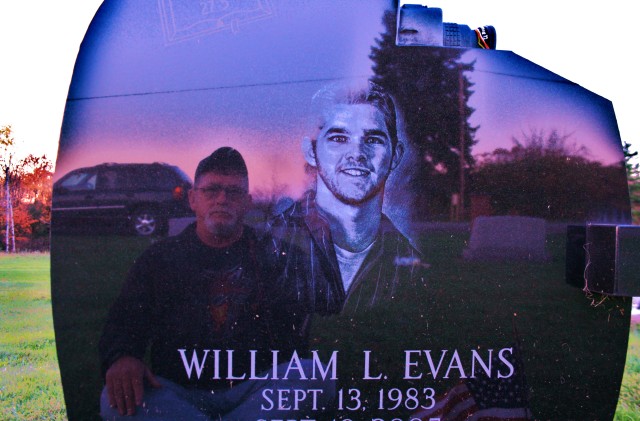

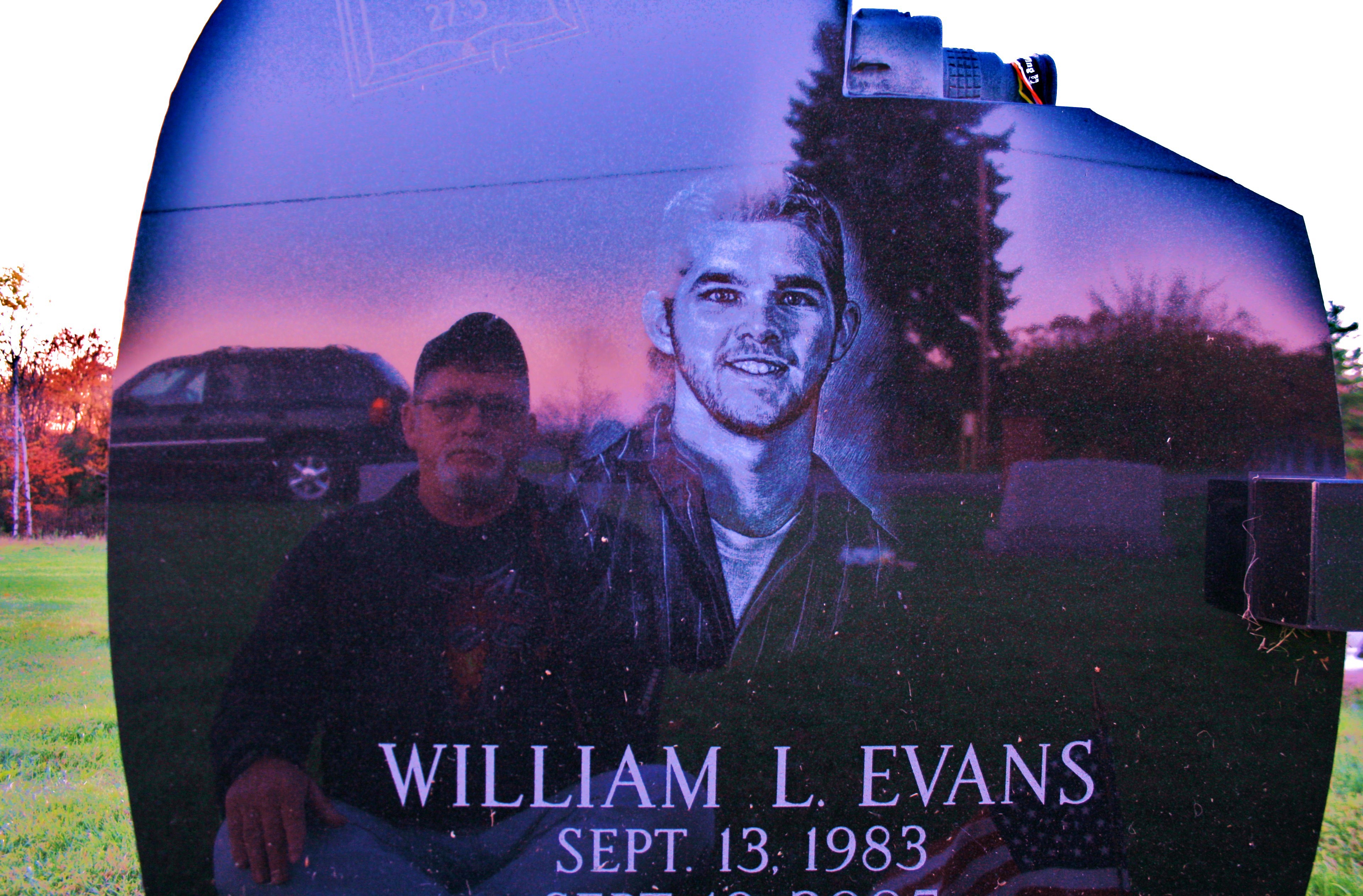

Specialist William Lee Evans was on patrol in Ramadi, Iraq, when the vehicle he was travelling in was struck by an IED. Still alive but unconscious, Billy was medevaced to Baghdad, where he died from his injuries.

"Billy deployed to Iraq on Jan. 22, 2005. He and his buddies said to each other, 'We have a job to do, so let's go over there and kick some butt, get it done, and come home.' And that's what they did. Some just didn't return to their Families," Bill L. Evans, Billy's dad, said.

Billy's parents learned about their son's death on a cloudy and unusually warm day eight months after his deployment, seven days after his 22nd birthday.

"I had just climbed into bed after working the third shift with maintenance at the local school. My wife had left to take care of an elderly man with Alzheimer's and our son Josh was at work at the local auto parts store. The doorbell rang and then someone began knocking. I finally got up and pushed open the curtains.

"There stood two Soldiers in Class-A uniforms. I knew immediately why they were there. When I opened the door, my first words were, 'I hope you're not here to give me bad news.' But there they were telling me my First-born son had been killed by an IED in Iraq. Crying, I collapsed as they comforted me the best they could before driving me to my wife's work," Evans said.

"When the notification officers arrived at the door," said Judy Evans Parker, "I told them there was no need to tell me what I already knew. My son had called me from sleep early that morning by sending my guardian angel to tell me he was gone. I felt life leave him. I felt his weakness and blood drain from him. A mother knows when her child needs her. Thousands of miles between us and we still know," she said. In memory of Billy, his dad got a tattoo inked into each arm. He also had a camera carved on Billy's headstone, to symbolize their shared passion for photography.

"I have all his medals and ribbons in the living room for everyone to see. Photographs of Billy remain in our home plus the flag, dog tags, and awards. Keeping his personal items in sight reminds me that his service and death was a sacrifice he made for all of us," Evans said.

Iraqi insurgents captured Staff Sgt. Matt Maupin, April 9, 2004, after his convoy came under attack by rocket-propelled grenades and small arms are near Baghdad. His mom, Carolyn Maupin, began to consider getting inked, but was a bit hesitant.

"My daughter Lee Ann got tattoos while she was in college and I was not too pleased with her. But this past year I began to think of getting a tattoo, too. So I asked everyone who had one if it hurt. To my surprise, most said it didn't," she said.

Carolyn gave herself the deadline of Memorial Day, 2010 to have one completed.

"During the four hours it took, I had Matt's chain on with his dog tag that has his picture so when it hurt I would say, 'Matt, if you can do for me what you did, I can surely do this.' Even during the process, I felt closer to Matt. Even though he can't be here with me, this tattoo symbolizes his physical presence. There is a hole in my heart that will never be filled. Our fallen should never be forgotten. The tattoo opens conversation so that I may tell Matt's story," Maupin said.

Sergeant Patrick D. Stewart died in combat in Afghanistan when insurgents used a rocket-propelled grenade to shoot down his Chinook helicopter, Sept. 25, 2005. His wife, Roberta, was able to complete the tattoo in his honor in three sessions over six months, before the five-year anniversary of his death. "I started to feel numb and decided on getting the first of 12 tattoos because I wanted to feel the pain. It makes me happy I'm doing something in memory of him," Stewart said recently at a Survivor Outreach Services summit in Arlington, Va. Her tattoo, located on her leg, is a crying eagle whose tears create a waterfall that flows down over the Chinese emblem for dreams and into a pond with a four-leaf clover for better luck. "The pain was unbearable on my ankle. The bone hurt the most," she said. "It represents the sacrifices my husband made and gives me a better connection with his spiritual realm," For more than 5,000 years these permanent designs have continued to serve as amulets, status symbols, declarations of love and signs of religious beliefs. But during the past 10 years of persistent conflict, this tradition is gaining wider acceptance as a way to remember.

For Soldiers, battle buddies and Family members, getting inked has become a statement to the world that someone close to them has fallen. It makes no difference how they fell, only that their memory will live on for all to see.

ARMY TATTOO POLICY

With the growing popularity of tattoos, the Army revised its policy four years ago with Army Regulation 670-1.

The change was made because Army officials realized the number of potential recruits bearing skin art had grown enormously over the years.

About 30 percent of Americans between the ages of 25 and 34 have tattoos, according to a Scripps Howard News Service and Ohio University survey. For those under age 25, the number is about 28 percent. In all, the post-baby-boom generations are more than three times as likely as boomers to have tattoos.

As a result of tattoo attitude changes, Army Regulation 670-1, chapter 1-8E (1) has been modified via an ALARACT 017/2006 message.

Additionally, paragraph 1-8B (1) (A) was revised to state: "Tattoos that are not extremist, indecent, sexist or racist are allowed on the hands and neck. Initial entry determinations will be made according to current guidance."

The new policy allows recruits and all Soldiers to sport tattoos on the neck behind an imaginary line straight down and back of the jawbone, provided the tattoos don't violate good taste.

Social Sharing