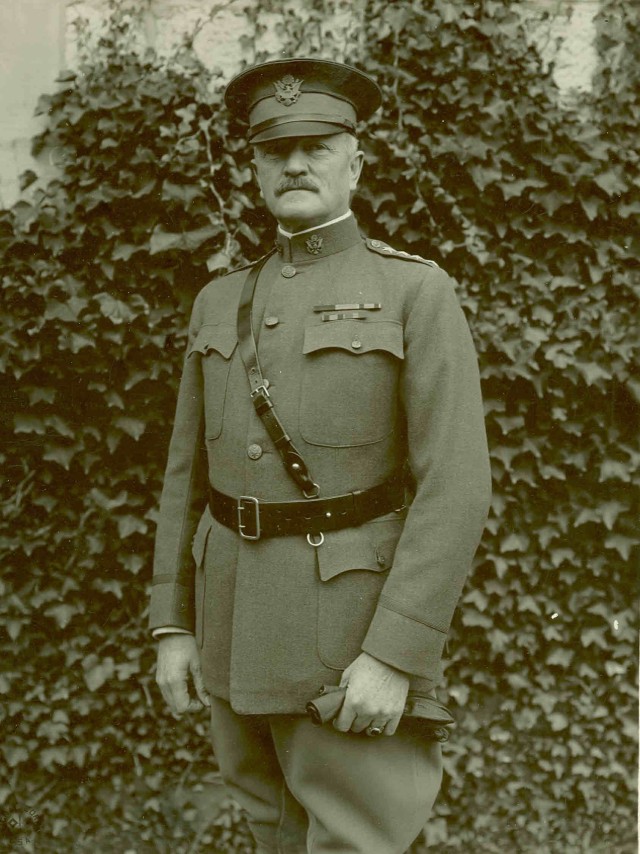

In early December, 1917, American Expeditionary Forces Commander General John Pershing warned the Secretary of War that with the collapse of the Russian front, the Germans would be able to concentrate as many as 260 divisions on the western front in the spring. Against that force, the allies had just 169 divisions. Pershing judged that it was "very doubtful" that the allies could stop the Germans given the disparity in manpower.

Part of the problem stemmed from the mismanagement of American mobilization. Preparing America for a major war was a monumental challenge, characterized by so much inefficiency and corruption that Secretary of War Newton Baker had offered to resign. Despite having been technically at war since April, the United States had just four infantry divisions in France, and they were all short on training, equipment, and modern staff techniques. Pershing estimated that the United States would need to have at least 24 divisions on the western front by June for the Allies to have a chance to stop the expected German attack. At the time, few Americans (and even fewer Europeans) held out much hope that the Americans could meet this need.

One solution offered by the Europeans, known as amalgamation, would have the United States insert its men directly into existing British and French units at the company level. Europeans argued that amalgamation would compensate for the inexperience of American officers and NCOs as well as American lack of familiarity with modern staff arrangements and technologies like aviation, armor, and heavy artillery. American troops would thereby be commanded at the tactical level by American junior officers, but the operational and strategic direction of American forces would be handled by more experienced Europeans.

President Wilson, like most other Americans, was initially aghast at the idea of amalgamation. Some Americans looked at the enormous casualty levels on the western front and recoiled against the thought of their young men being used as cannon fodder by European generals. Pershing contended that the Europeans had become too tied to trench warfare; his "open warfare" doctrine, he argued, would restore mobility to warfare by emphasizing American aggressiveness and marksmanship. Wilson and his political advisors also recognized that an amalgamated American force would not allow for a distinctive American presence on the western front. Wilson knew that he would need to be able to point to an American contribution to victory if he were to represent American interests in any post-war peace conference.

Wilson therefore gave Pershing a written order before his departure for Europe forbidding him from amalgamating American forces. Pershing stubbornly held to his position that American forces would only fight under a completely American chain of command on a distinctly American section of the western front. At one point, he even told French Premier Georges Clemenceau that he was prepared to see allied forces pushed back to the Loire River (meaning the loss of Paris) rather than amalgamate American forces into larger European units.

Yet it was obvious that the Americans were not yet ready to fight on their own. Having held to a strict definition of neutrality, the Americans had had virtually no opportunity to learn about modern war. They needed time to learn about trench warfare and modern tactics. They also needed time to build relationships with their French and British allies and to overcome the inefficiencies of their own mobilization. Few doubted that they could do it. The question was whether they would complete these enormous tasks in time to stop the German spring offensive.

The solution came in the form of an agreement signed in mid-December, 1917. It read "in compliance with the request of Great Britain and France, prompted by the expectation of a strong German offensive, the President agrees to the American forces being, if necessary, amalgamated with the French and British units as small as the company." The final decision on the level of amalgamation was to be Pershing's.

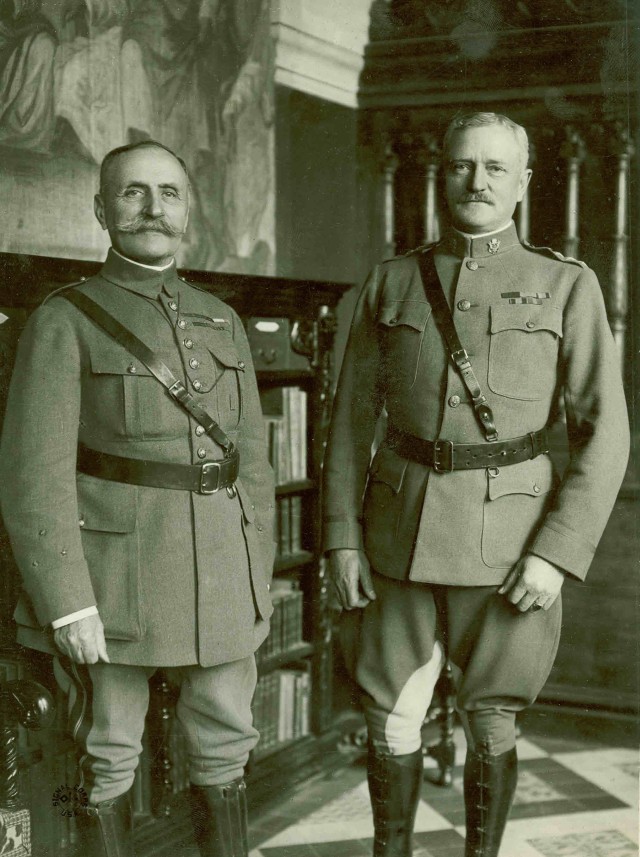

The decision was undoubtedly the right one and probably saved thousands of American lives. Pershing ultimately decided to amalgamate at the division level, meaning that American soldiers took their orders from American officers up to the level of major general, but overall strategic direction came from more experienced French officers at the corps, army, and army group levels. This system functioned well at the watershed Second Battle of the Marne in July, 1918, and gave the Americans the crucial experiences they needed to fight a coalition war and make their mark on the final victory. It also provided General Dwight Eisenhower with the model he used in building his own coalition in the Second World War.

ABOUT THIS STORY: Many of the sources presented in this article are among 400,000 books, 1.7 million photos and 12.5 million manuscripts available for study through the U.S. Army Military History Institute (MHI). The artifacts shown are among nearly 50,000 items of the Army Heritage Museum (AHM) collections. MHI and AHM are part of the U. S. Army Heritage and Education Center, 950 Soldiers Drive, Carlisle, PA, 17013-5021. Website: www.carlisle.army.mil/ahec

Social Sharing