Global air mobility is one of the most important capabilities of AmericaAca,!a,,cs armed forces. It provides our army with the flexibility and range required to quickly and effectively take the fight to our enemies. The origins of this unique capacity to move masses of soldiers and equipment through the air can be found in the early days of World War II, when a handful of soldiers and airmen fought to stem the tide of Japanese conquest in the southwest Pacific.

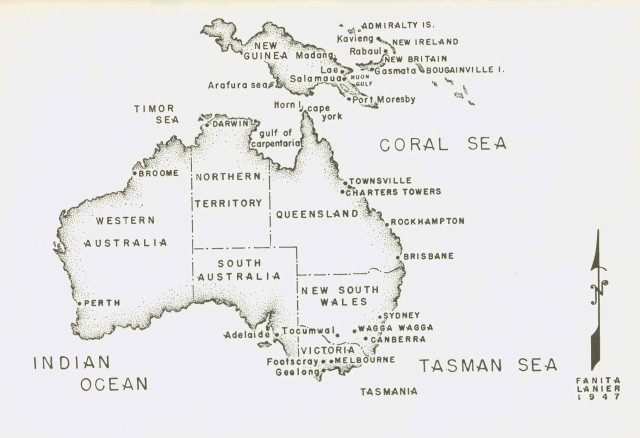

The United States and their Australian allies were in a very difficult position in the late summer and early fall of 1942. The empire of the rising sun was at its zenith, and the Allies seemed powerless to stop it. In July the Japanese landed on the island of New Guinea, located just north of Australia. Pausing only to consolidate their beachhead and bring in additional supplies and reinforcements, they marched south across the island, over the rugged spine of the Owen Stanley Mountains, toward the Allied strongpoint at Port Moresby. They planned to capture this important base and force the Allies to withdraw from New Guinea, leaving Japan in a perfect position to isolate and perhaps invade Australia.

After weeks of bitter fighting Australian troops had successfully blocked the Japanese assault, but reinforcements were needed to strengthen the defenses at Port Moresby and prepare a counterattack. General Douglas MacArthur ordered that elements of the newly arrived U.S. 32nd Infantry Division be sent from Australia to New Guinea as quickly as possible.

Shipping was in short supply, and the passage from Australian ports to New Guinea would take days. The dire military situation and limited resources forced the Army to innovate, improvise and take risks. Major General George Kenney, the Allied air commander, urged General MacArthur to fly American combat troops along with their arms and equipment from Australia to Port Moresby. Kenney insisted that this could be accomplished quickly and without loss. Many were skeptical; the airstrips in theater were crude, the soldiers and airmen untrained, the distances vast, the airspace contested and the inventory of aircraft unsuited for such an operation. Nevertheless, MacArthur was intrigued, but he wanted to see a successful demonstration before approving the plan. He authorized Kenney to fly one combat loaded infantry company from Australia to New Guinea, stating that if the effort was successful, he would grant permission to airlift an entire regiment.

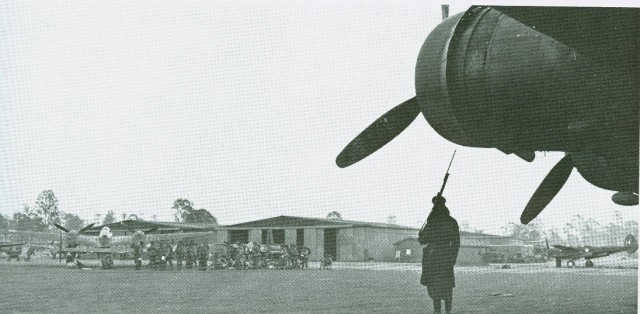

The commander of the 32nd Division selected a force of 230 men consisting of Company E, 126th Infantry Regiment, a platoon of engineers and a small medical detachment to test General KenneyAca,!a,,cs airlift plan. To overcome the shortage of transport aircraft, heavy bombers scheduled for overhaul and civil airliners (arriving complete with stewards and a beverage service) were tapped to support the airlift. The men of the task force arrived at Amberly Field in Brisbane in the early morning of September 15, 1942, boarded a motley collection of aircraft and started their long flight.

By six that evening General Kenney received word that the men had arrived safely and on schedule at Port Moresby. MacArthur was impressed and immediately gave Kenney the go-ahead to begin flying the 128th Infantry Regiment from Australia to New Guinea. This operation was the first airlift in American military history. The technique of using cargo aircraft to move large numbers of combat-ready soldiers to hastily prepared, forward airfields made it possible for Allied forces to bound westward across New Guinea and the wide Pacific.

By demonstrating the effectiveness of air mobility these courageous and innovative soldiers and airmen revolutionized warfare. They changed the way our Army projects power around the world.

Social Sharing