Responsibility for repelling the North Korean Communist hordes who shattered a Sunday morning's calm on 25 June by unprovoked invasion of South Korea is the latest task added to the heavy burden carried by the Far Easy Command. As Commanding general, Far Easy Command, and as Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, General Douglas MacArthur flew to Korea early in the conflict to observe the situation personally. On 8 July he was named Supreme Commander of United Nations Forces in Korea.

Just five years previously, after leading his forces to a military victory, General MacArthur began the direction of an occupation effort that has achieved a transformation without equal in so short a time. Today despite the renewal of armed conflict in Asia, his occupation forces--both military and civilian--are continuing rehabilitation efforts, paving the way for an ultimate peace treaty and for the admission of Japan to a family of nations dedicated to the goal of world peace.

Regardless of the flare-up of armed aggression, the occupation of Japan may be summed up on VJ day this year as a symbol of the progress possible through democratic processes.

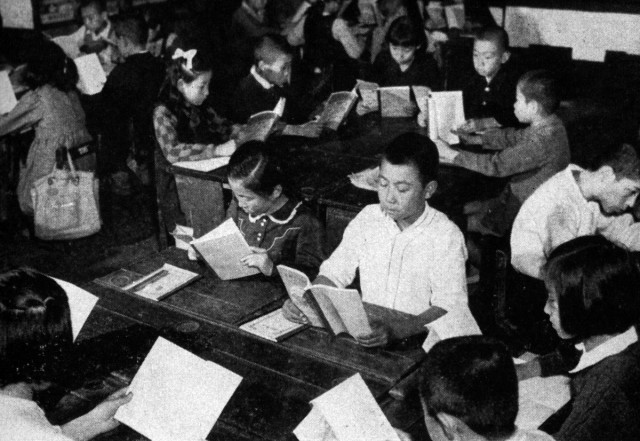

In the new Japan, women vote, workers join free labor unions, farmers may own the land they till so painstakingly, boys and girls attend the same schools and worshipers are free to attend the churches of their choice. Such activities so so commonplace to Americans were undreamed of by the average Japanese when his country was first occupied.

Under Japan's pre-surrender government the individual had no political liberty, no safeguards against arbitrary arrest or imprisonment, no protection against search and seizure of his home and little if any recourse in the event of seizure of his possessions. In short, respect for the dignity of the human being was not part of official thinking in pre-occupation Japan.

The Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers toppled the feudalistic structure through a series of directives that laid the foundation for a new democratic society. In a precedent-shattering first year, the Japanese military machine was demobilized and disarmed, the sovereignty of the Emperor was transferred to the people, universal suffrage was enacted, a militaristic police system was reformed, freedom was given to political parties, labor was granted the right to organize and bargain collectively and religion was eliminated as an instrument of the state.

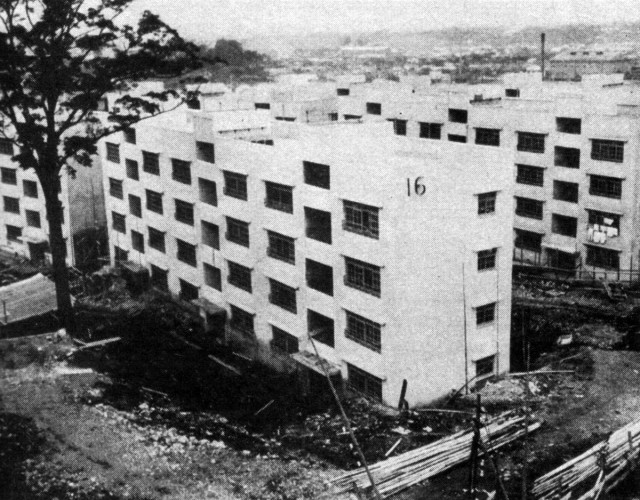

Major reforms continued in the second year. A new constitution was adopted making democratic rights the fundamental law of the land. The decentralization of Japan's national government was accomplished by popular election of local and prefectural (state) officials and granting local government wide powers and responsibilities. The civil code was revised in order to free women from virtual bondage by granting them social and economic equality. A land reform program was instituted to break up large land holdings and create a new class of small landowners from among the former tenants. Private trade with foreign countries was resumed on a limited basis as the first step toward restoration of normal economic life.

Significant in the reformation was the manner in which it was brought about. Japan had no direct military government such as in German or Korea. Instead, with the broad outlines for reorientation established, the Japanese were given the responsibilities for carrying out policies laid down in the Supreme Commander's directives. They were allowed to conduct their won affairs unless they violated the basic objectives of the occupation as outlined in the Potsdam Declaration.

The first steps toward political reorientation were the lifting of restrictions on freedom of thought, religion, assembly, speech and civil rights, and the liberation of political prisoners.

Japan's new constitution was promulgated on 3 November 1946. It transferred sovereignty to the people, giving them a Bill of Rights much like the one set forth at Philadelphia some 170 years earlier. Under the constitution the Emperor was retained as a limited monarch who participates in ceremonial functions of state but exercises no governmental authority.

Legislative power was vested in the Diet, with members of both houses elected by the people. Executive power was vested in a cabinet collectively responsible to the Diet, with the prime minister named by the Diet from its members.

The third branch of the national government created by the constitution was a 15-member Supreme Court empowered to determine the constitutionality of any law, order, regulation or official act.

Although not entirely comprehending at the outset the significance of the sweeping changes, the Japanese people accepted their new responsibilities with gusto. In the first fully democratic election, less than a year after the war's end, 72 per cent of Japan's eligible voters cast ballots for members of the Diet's House of Representatives.

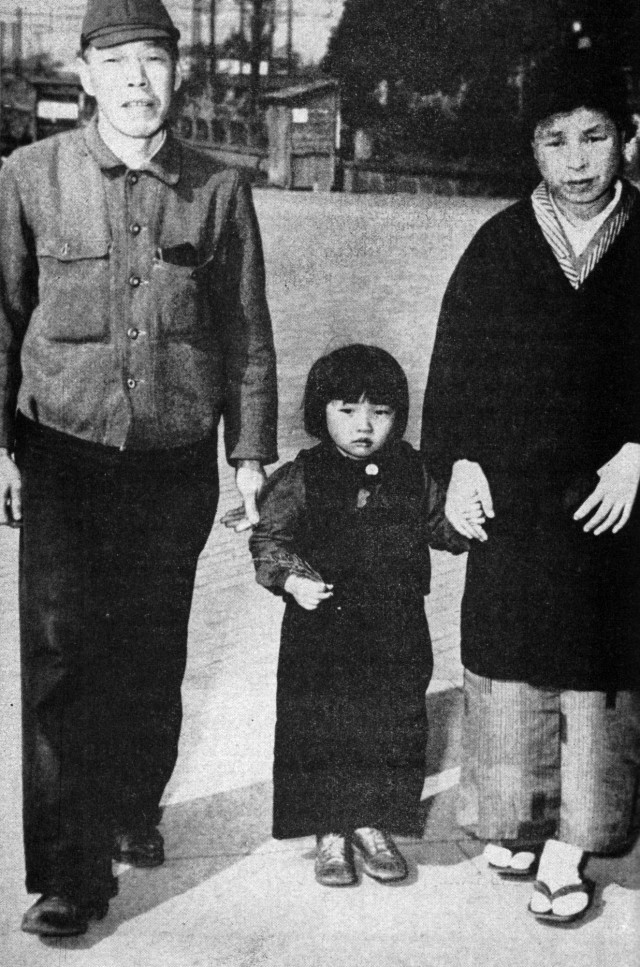

A year later, in the second general election, the effect of the occupation's decentralization program was seen. Under a new local autonomy law, elections were held for prefectural governors, city mayors, village headmen and assembly members. Nearly 2400 women ran for national and local office and more than 800 were elected, including 10 to the Diet's upper house. Women at last had a voice in governmental affairs.

SCAP's directive establishing civil liberties--issued a few weeks after the occupation began--was followed by instructions that labor unions be encouraged. The Diet passed a law guaranteeing workers the right to organize and bargain collectively. Unions were forced at an unprecedented rate. Labor organizations and their memberships jumped from five unions with 5300 members in October 1945 to 36,000 unions with nearly 7,000,000 members by the middle of 1949.

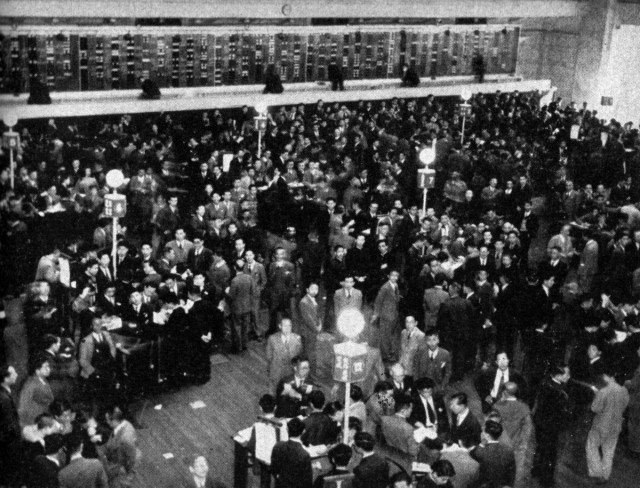

Meanwhile, business also was being decentralized. The Japanese economy before and during the war was dominated by the Zaibatsu--a few powerful families who controlled the major part of Japan's industry, mining, finance and commerce and, to a large extent, the livelihood of the Japanese people.

The Zaibatsu's stranglehold on economic enterprise had to be broken while foundations for a competitive, private enterprise economy were laid. Much of the stock of Zaibatsu companies and combines sold to employees, local residents and the general public. Aside from the Zaibatsu, large holding companies, monopolistic trading combines and control associations, whose fingers reached into practically every area of business and industry, also were broken up.

Democratization of Japanese business in the cities was complemented in rural areas by a Land Reform Program that turned millions of tenant farmers into free landholders. Prior to the occupation 70 per cent of Japan's farmers rented all or part of their land and generally were required to pay in kind from 50 to 70 per cent of their gross farm output as rent. Since the occupation began, more than 4,500,000 acres involving 30,000,000 tracts have been bought by the government from former landowners for resale to the farmers.

The formation of agricultural cooperatives free from domination by government or other outside control was encouraged. By mid-1949 a total of 31,329 local and individual co-ops had been organized.

Cooperatives also were established in the vital fisheries industry. The Japanese, probably to a greater extent than any other nation, have developed resources of the sea. Practically every species of sea animal and plant is used for human consumption or industrial purposes. Much of the fishing industry was under the control of fisheries associations dominated by the government and by local village bosses. Under the occupation, these associations were replaced by cooperatives operated though democratic procedures. By last fall 89 per cent of Japan's 3131 fishery associations were in process of dissolution and 811 cooperatives had been formed.

In 1948 the Japanese fishing fleet was restored to its pre-war level. By last year maritime production was approaching 7,000,000,000 pounds, the highest level since hostilities ended and considerable more than pre-war production from the same area.

Historically Japan has been a food deficit country. Through the use of all land resources, Japan held food imports in the past 20 years to an annual average of 3,000,000 tons. About 85 per cent of the country's food requirements came from indigenous production. With the end of the war, the Japanese food collection and distribution system faced total breakdown.

If disease and unrest were to be prevented, the occupation authorities had to obtain maximum production of food, provide an equitable distribution system for it and import the minimum quantities necessary to make up the food shortage. Rice collections from farmers had dropped to 19,000,000 koku (One koku equals 4.95 bushels) in the 1945-46 crop year, compared to about 36,000,000 during the war years. They were increased to 27,000,000 koku in 1946-47, 29,000,000 in 1947-48 and 31,000,000 in 1948-49.

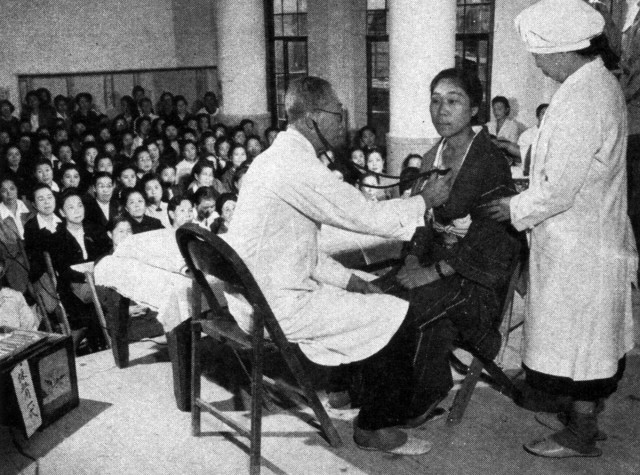

Prior to the surrender, health and welfare activities that existed in Japan were primitive and inefficient. Public water and sewage systems, which existed only in the larger cities, had suffered damage. Environmental sanitation was virtually non-existent, presenting a threat of dysentery, typhoid and typhus epidemics.

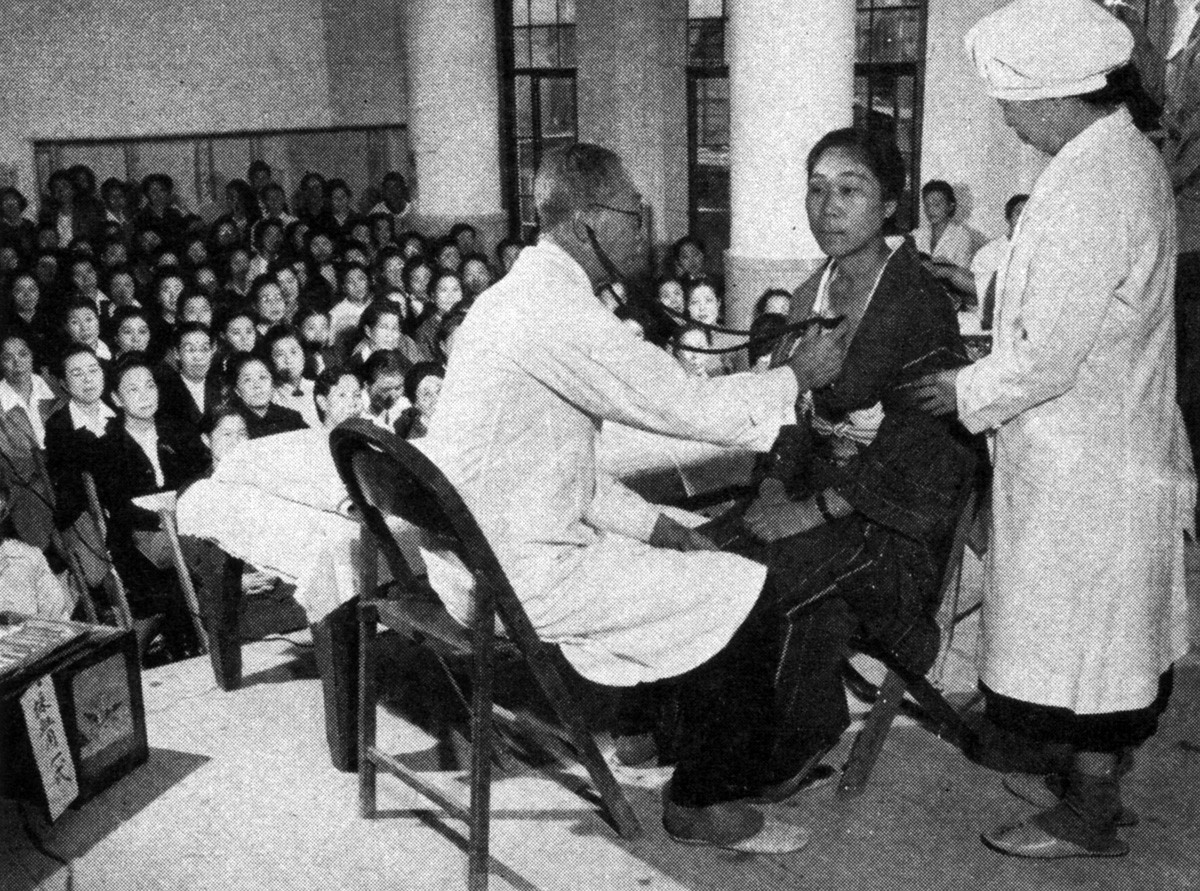

Smallpox, which was becoming increasingly dangerous, has been practically eliminated as a major public health problem through vaccination of Japan's entire population. Typhus fever, endemic in Japan for years, has been dealt with through the vaccinating of nearly 9,000,000 people and the dusting of 48,000,000 with DDT. At least 34,000,000 persons were immunized against cholera. Japan's diphtheria rate was reduced 83 per cent by instructing Japanese pharmaceutical plants on how to make the necessary toxoid and by immunizing several million school children. Improvement of sanitation and water supplies, the control of insects and rodents, and an immunization program brought decreases in dysentery and typhoid by more than 85 per cent.

But the big health problem in Japan was tuberculosis, the leading cause of death since 1934. Japan's tubercular rate was one of the highest in the world. By the use of full publicity, mass examinations in factories and schools and the inoculating of millions, the death rate from tuberculosis was reduced from 280 per 100,000 annually in 1945 tot 181 per 100,000 in 1948.

In the early stages of the occupation all foreign trade had been conducted between governments. In 1947, however, limited private export trade was begun and private traders were permitted to enter Japan. Since then constant simplification and normalization of trade procedures have been carried out in order to reestablish foreign trade on a free competitive basis.

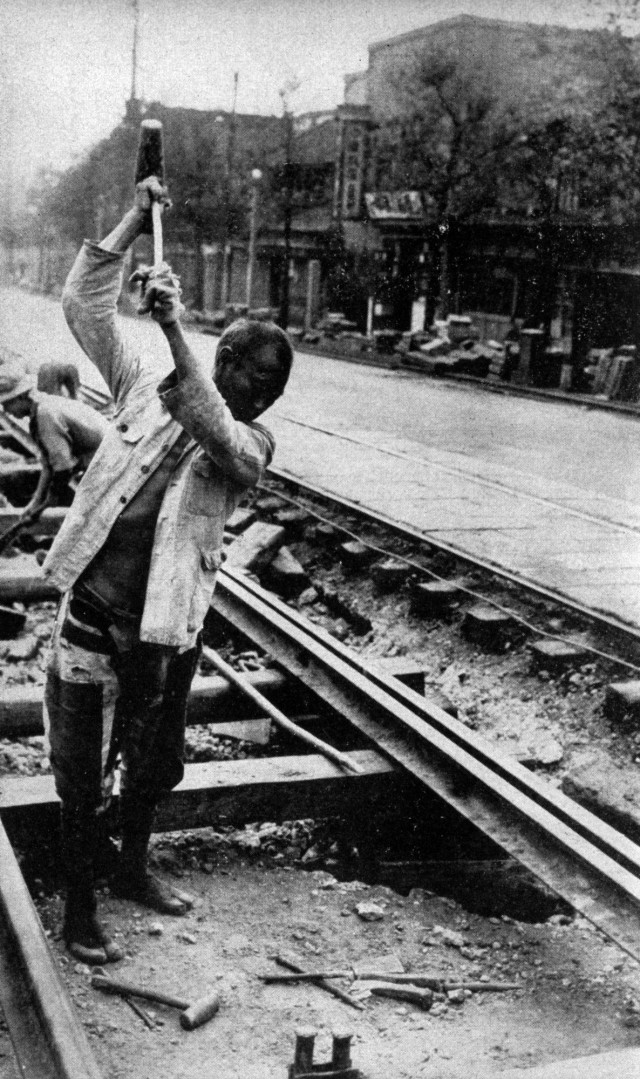

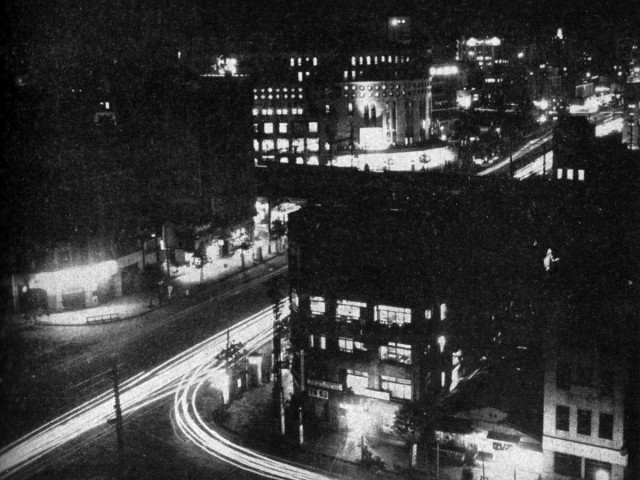

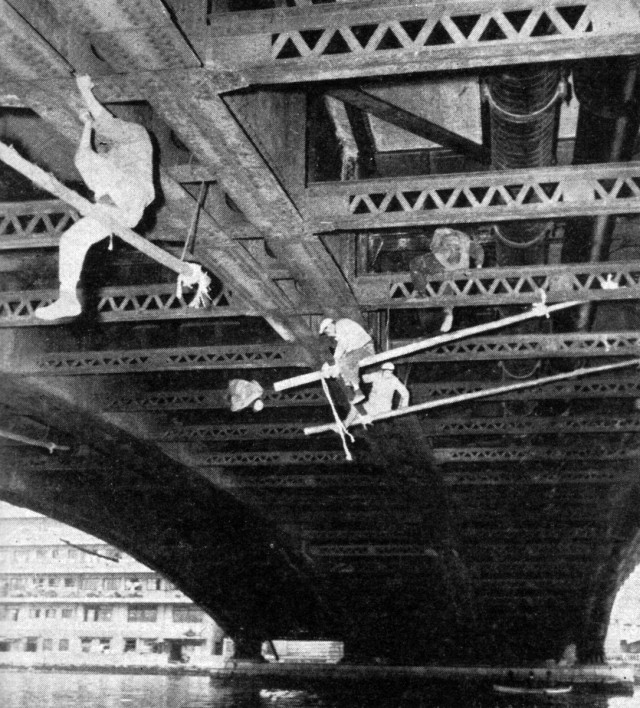

Progress toward economic rehabilitation is reflected in the fact that industrial production, which gained 30 per cent from July 1948 to July 1949, continued its upward trend. Production rates in coal, utilities and other basic industries have approached and in some cases surpassed pre-war levels.

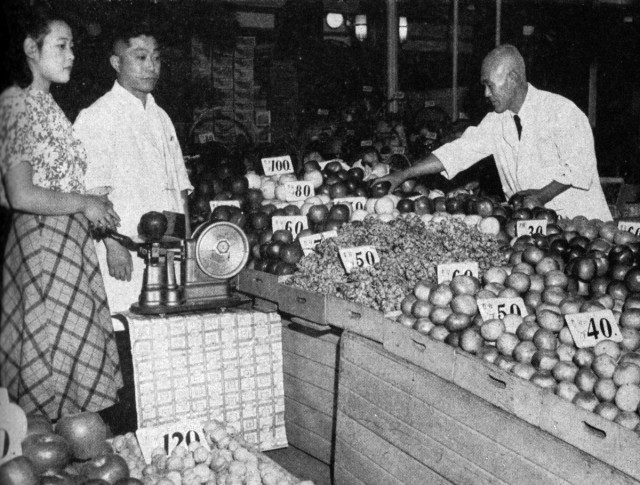

Consumer goods in vastly increased quantities are available to the Japanese people. Economic controls through rationing, price ceilings and subsidies have been eliminated on numerous items. In an important relaxation of controls, export trade was returned to a private basis on 1 December 1949 and import a month later. In both of these instances, the government retained only such controls as were necessary to safeguard Japan's foreign exchange position, the stability of her currency and the equitable distribution of scarce essential commodities.

The progress achieved in five years of occupation has vital significance for the free nations of the world today. Against the backdrop of battle in Korea, the economic revitalization of Japan and its stability and reorientation along democratic lines are among the unseen factors helping to smooth our path to victory over the forces of aggression.

Social Sharing