Sgt. Dan Smith is a 25-year-old active-duty Soldier. He was in his third month of a second deployment. This deployment triggered terrible memories from his first deployment.

Until recently, he had been able to cope. Then, while on patrol, the unit was attacked by insurgents and Smith failed to return fire. In an instant, two guys in his unit were gunned down by the insurgents.

When Smith returned to the safety of the rear area, he began to think obsessively about the incident. He could not justify why his fellow Soldiers were killed and he was still alive. He was feeling extremely guilty.

Later that day, Smith was talking about the incident with his battle buddy, Sgt. Mullins.

"I should have died with my friends," Smith said.

As a very alert friend, Mullins asked Smith what he meant.

Smith explained that he could not understand how he had survived the firefight. He shared terrible feelings of guilt regarding his failure to fire his weapon. He wondered if his failure to fire back at the enemy caused the death of his fellow Soldiers. He revealed that the incident brought back painful memories of battle buddies lost during his first deployment.

Mullins listened to Smith for what seemed like a long time and then said, "Hey, I was in that firefight too. I don't think we could have done anything to save those guys."

Recalling his suicide intervention training on ACE, Mullins gathered his courage and asked Smith if he was thinking about killing himself. Smith hesitated for a moment and then said, "No, but I can't stop thinking that I should have died with the others."

Mullins was concerned about that answer and because he really cared about Smith, he suggested that Smith speak to the chaplain.

"The chaplain will help you make some sense out of this," he said. "Come on, I'll go with you to the chaplain's office. I need my old battle buddy back."

Smith agreed to see the chaplain. After a few sessions, he was feeling much better. He continued to mourn for his lost buddies; however, he no longer felt guilty.

This fictionalized story had a very satisfying ending: Smith was fortunate to have a battle buddy who cared enough to get involved. Mullins heard Smith's unusual comment. It caught his attention enough to alert him to implement his ACE ("Ask, Care, Escort") training, to the ultimate benefit of his friend. Mullins decided he had to get involved, and his decision to use ACE may have saved Smith's life.

Unfortunately, not all situations have a positive outcome like the story above. Far too often, Soldiers fail to intervene because they do not want to intrude into a buddy's privacy. Sometimes Soldiers just lack the courage or confidence to get involved. The Army needs Soldiers to be involved and intervene when a buddy appears to be struggling with a problem. Suicide in the Army has become a matter of great concern. In order to stop suicides, Soldiers must be more vigilant and willing act on their ACE training.

A key element of suicide prevention is for Soldiers to recognize when a fellow Soldier may be at risk for suicide, ask about it, and assist the Soldier who is thinking about suicide to get specialized help. The assumption is that Soldiers know each other best, and understand and relate to common experiences.

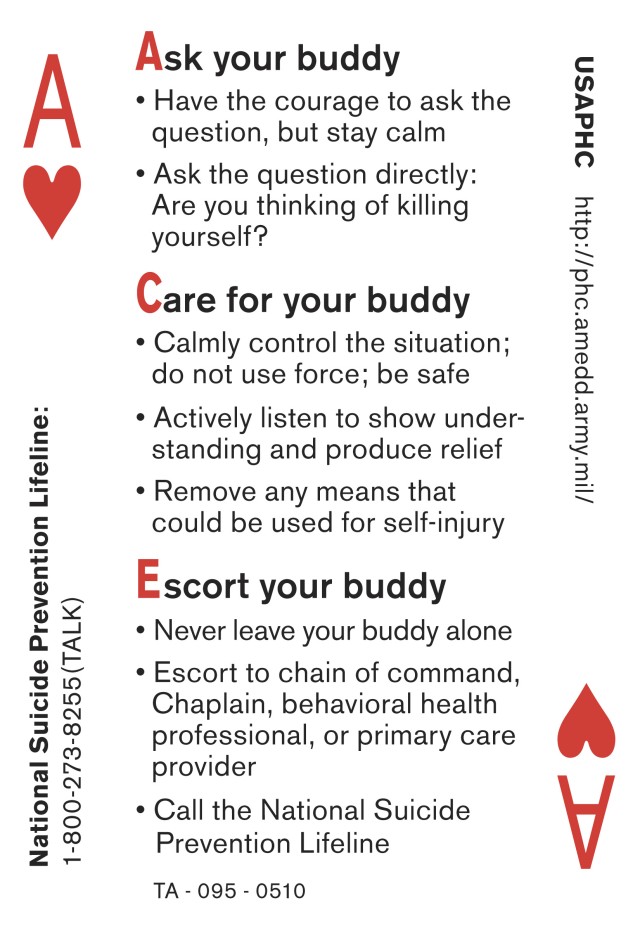

The Army ACE acronym is used to reinforce the basic concepts needed by a battle buddy in order to help a suicidal Soldier. Ask your buddy about his or her suicidal thoughts. Care for your battle buddy by understanding that your battle buddy may be in pain. Escort your battle buddy immediately to your chain of command, chaplain or behavioral health professional.

The Army has developed an easy to learn ACE intervention training program. ACE training can play a role in the unit's resolve to help prevent suicide. A unit member's suicide negatively affects unit cohesion. A suicide can demoralize and seriously disrupt the unit's ability to sustain its mission. Given this perspective, Soldiers and leaders have a vested interest in helping buddies who are thinking of suicide. If all Soldiers develop awareness and intervention skills at the individual level, they become a competent and confident force for preservation of life within the unit.

Social Sharing