Fort Benning, Ga. - Folke Ahlquist was 11 years old in 1963 when construction was completed on Fort Benning's headquarters, Building 4, at a cost of $10 million. The post, not yet 50 years old, had long outgrown its original headquarters in Building 35. The completion of Building 4 was heralded in local papers as a major milestone in Fort Benning's history. It was modern, futuristic and "state-of-the-art."

It didn't much matter at all to young Folke, who lived in South Columbus with his mother and father, a Finnish immigrant from whom he had inherited his name. Trips to post usually centered on shopping at the commissary and the occasional visit to the U.S. Army Marksmanship Unit, where the elder Ahlquist worked. Fort Benning was the best place to catch a fire-works show each Fourth of July, but mostly, it was just a place where the dads of the kids in South Columbus went to work each day.

The elder Ahlquist was a World War II veteran who found a bride in Germany and brought her back to the U.S. He spent most of the remainder of his career at Fort Benning, except for one tour in Korea and two in Vietnam. His two children were born at the post hospital when it was located in old World War II-era barracks on what is now Sacrifice Field, more than a decade before Martin Army Community Hospital was built.

The father retired from the Army as a master sergeant in 1971, the year the son graduated from Pacelli High School. The elder went right back to work on Fort Benning, and the younger went off to earn a bachelor's degree in building construction at Georgia Tech.

He returned to Columbus four years later and, after a few years in the private sector, landed a job with the Directorate of Public Works. Just like his father, Ahlquist went to work on Fort Benning day after day after day. As an electrical engineer, he worked on nearly every non-residential building on post and came to appreciate the history of them all. Fort Benning's history was his history.

In 1998, Ahlquist accepted a position with the Army Corps of Engineers on the installation, and he's worked with them ever since. As a project manager, he finds himself now smack-dab in the middle of what's shaping up to be the most rewarding project of his career, the renovation of Building 4.

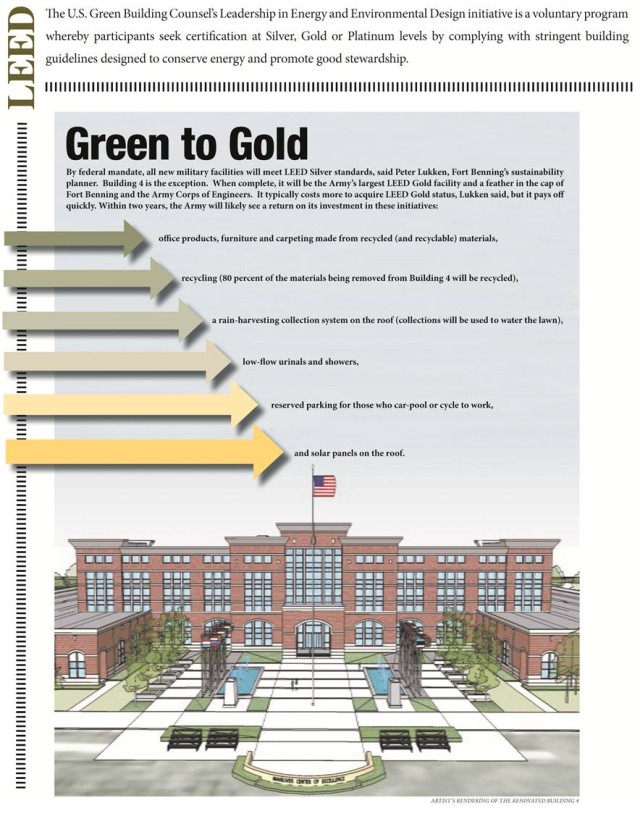

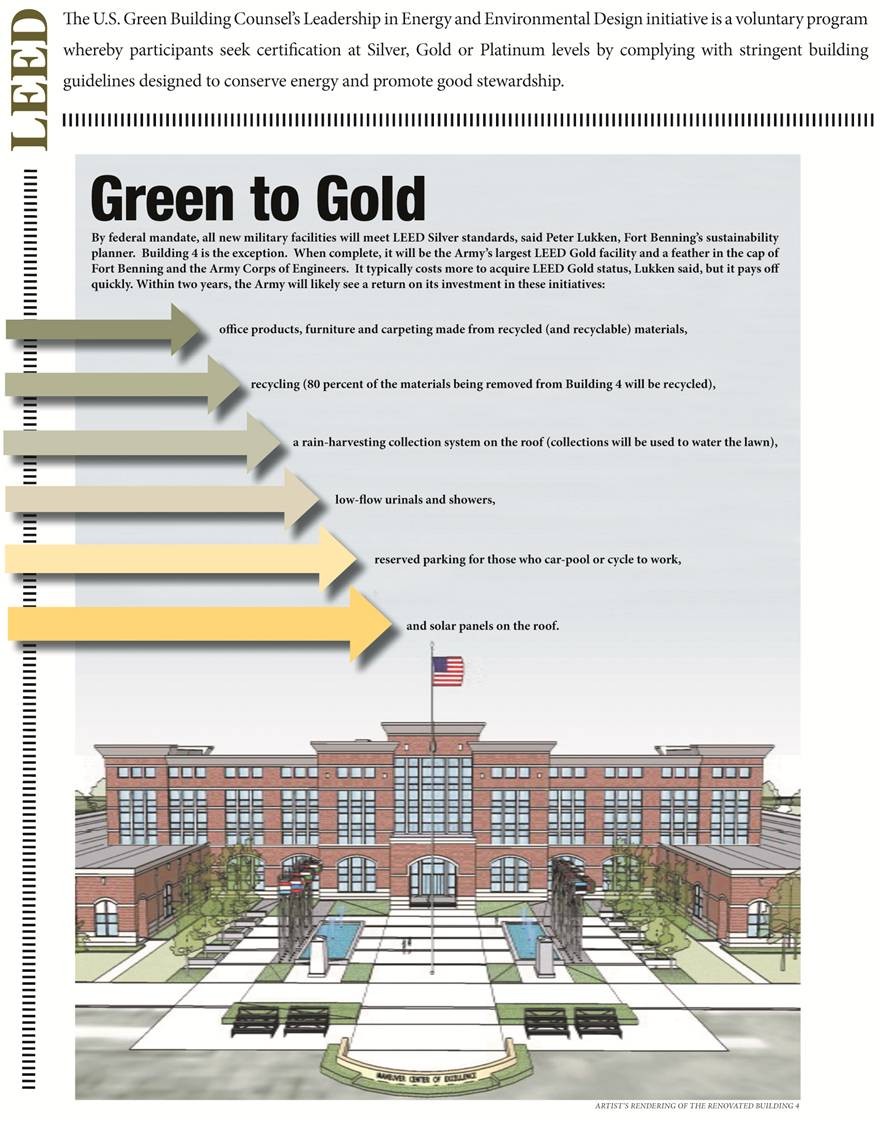

The $170 million project includes stripping the 500,000 square foot building to its skeleton and rebuilding it to be sounder, safer and more efficient. The finished project, with a red-brick, neo-traditional faAfASade, will look nothing like the Building 4 that caused such a stir back in 1963. But one thing won't change.

"The history's still there. To me, it's still Building 4, where so much of the history of Fort Benning took place, and that was really important to all of us," said Ahlquist, who has worked on the project with a team of about 12 developers since day one.

In 2005, the decision was made to renovate the building, rather than build fresh on another site, a decision that saved the Army more than $50 million and freed up funds for the renovation of "swing spaces," facilities being used to house the staffs that moved out of Building 4 for the duration. That decision added impetus to the renovation project, Ahlquist said.

"Personally, it gave me some extra incentive to put a tremendous effort into this job. Building 4 represents the history of this post and the Infantry," he said. "It makes it a little more enjoyable, a little more worthwhile and satisfying, to be a part of something so significant. The building will look very different than the original, but it will still have the same footprint. It'll still be Building 4."

The project is being completed in three phases, first the six-floor central "tower," where the offices of the post commander and the commanders of the Infantry and Armor schools will be located, then the east and west wings, which will mostly consist of classrooms.

Staffs began clearing out of Building 4 last spring. This time next year, they'll begin repopulating the tower. They will return to a space much safer and more environmentally friendly than before, Ahlquist said.

The building's original design might have succumbed to progressive collapse, a phenomenon that occurs when damage to one floor causes successive failure to others, much like the collapse of the Twin Towers. Now, steel rods are being used to reinforce more than 40 columns throughout the structure and a carbon fiber mesh is being applied here and there to add stability.

The building will also be much lighter. The butter-colored exterior bricks have been removed, as have most of the 60s-era heavy red clay tiles that formed a second, interior layer. This time around, the exterior bricks will be attached to metal framing, making the whole structure lighter and more resistant to the kind of damage that results from seismic activity or high winds.

The new faAfASade will be better suited to its surroundings, Ahlquist said. A team from HSMN Architects, lauded for their work on the Pentagon, designed the faAfASade to "fit in better" with the post's historic buildings, like the red-brick cuartels, he said.

Though the footprint won't change, the interior is being designed to feel more spacious, with the efficient use of sustainable furnishings and modular, reconfigurable walls.

This time around, all of that matters to Folke Ahlquist, who finds himself in a unique position - preserving the past and shaping the future. He hopes generations of Army families will benefit.

"I hope Building 4 is around for another 100 years," he said. "It's not just a landmark, it's a piece of Army history."

Social Sharing