BASTOGNE, Belgium -- The crisp, winter sun burned through the fog around noon in the town of Longchamps, Belgium, Jan. 3, 1944, revealing a wall of German tanks aligned on the snow-capped hillside.

No sooner did 2nd Lt. Everett "Red" Andrews call the target back to his fellow troops in the 377th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion, than he was struck through the mouth by shell fragmentation from the ensuing German onslaught.

"I hold the record for the shortest time spent as a forward observer ever," he joked, before calmly describing the scene in graphic detail. "I peaked my head above the fox hole to see if we hit the targets, and next thing I knew I was clutching the blood from my mouth in my hands and trying to put it back in me. I thought I was going to die. I was twenty-two years old, I didn't know. I guess besides my bright red hair at the time, that was another reason folks call me 'Red.'"

The fragmentation is still lodged in his lower jaw, sixty-five years after forcing his early exit from the seminal World War II Battle of the Bulge, the largest land battle in U.S. Army history.

Andrews received a Purple Heart for his injuries suffered during the battle. He is quick to defer the significance of his service and the harsh conditions he experienced, first mentioning the hardship of the infantrymen he served alongside.

"I have the utmost respect and admiration for the infantry Soldiers, who have experienced the most severe conditions imaginable," said Andrews, who rose to the rank of colonel during a 20-year military career. "They had very miserable experiences. Compared to them, I had it easy. They were in foxholes in the bitter cold, I lived in a house in the village."

Andrews was referring to his time living with a Belgian family from a nearby village who welcomed him into their home during the battle.

"The Belgian people showed us tremendous warmth and gratitude for being there with them," he said. "I stayed with one of the few families in the area that did not evacuate when the Germans arrived. They didn't speak English and I spoke pidgin French, but we were able to form a very deep bond. They looked on us as protection from the Germans."

The Leroy family included Arthur Leroy, his wife Madeline, and four small girls named Elise, Madeline, Irene and Gilbert. Their home was half living quarters, and half cow stables. For warmth, the family of six slept with the cows at night, leaving Andrews and his Soldiers to sleep in the house in sleeping bags. They would spend free time sharing stories about the war, joining the family's radio with the troops' generator to keep updated.

Andrews stayed in contact with the family after the war, first reconnecting with the family the following December while stationed at Camp Oklahoma City near Rheims, France, awaiting orders stateside.

"I was glad to see them living about as well as anyone should after the war," he said in his down-home manner. "I felt like part of the family. I've been back for many of the major anniversaries of the war, and have visited them each time."

In 1994, Andrews was back in Belgium for the 50th anniversary of World War II. To his surprise, the Leroy family had arranged for a tree in the "Bois de la Paix" - "Woods of Peace" - a memorial of 4,000 trees started by the town of Bastogne to honor U.S. and Belgian veterans who fought in the Ardennes. Each tree bears a plaque with a soldier's name inscribed. From the air the layout of the forest is designed to resemble the mother and child in the emblem of the international human rights organization UNICEF.

"I was deeply moved by that," Andrews said. "I was overwhelmed by the appreciation and gratitude here."

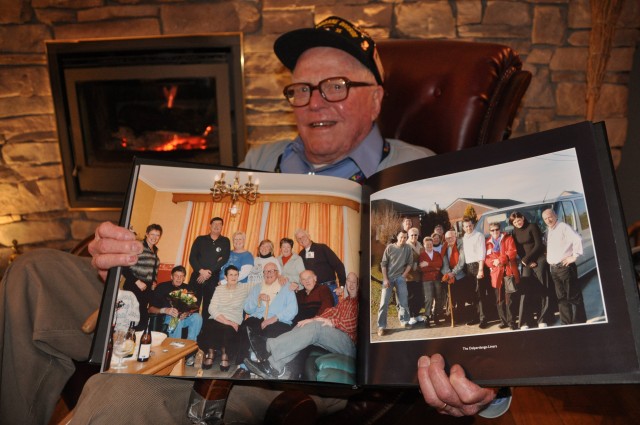

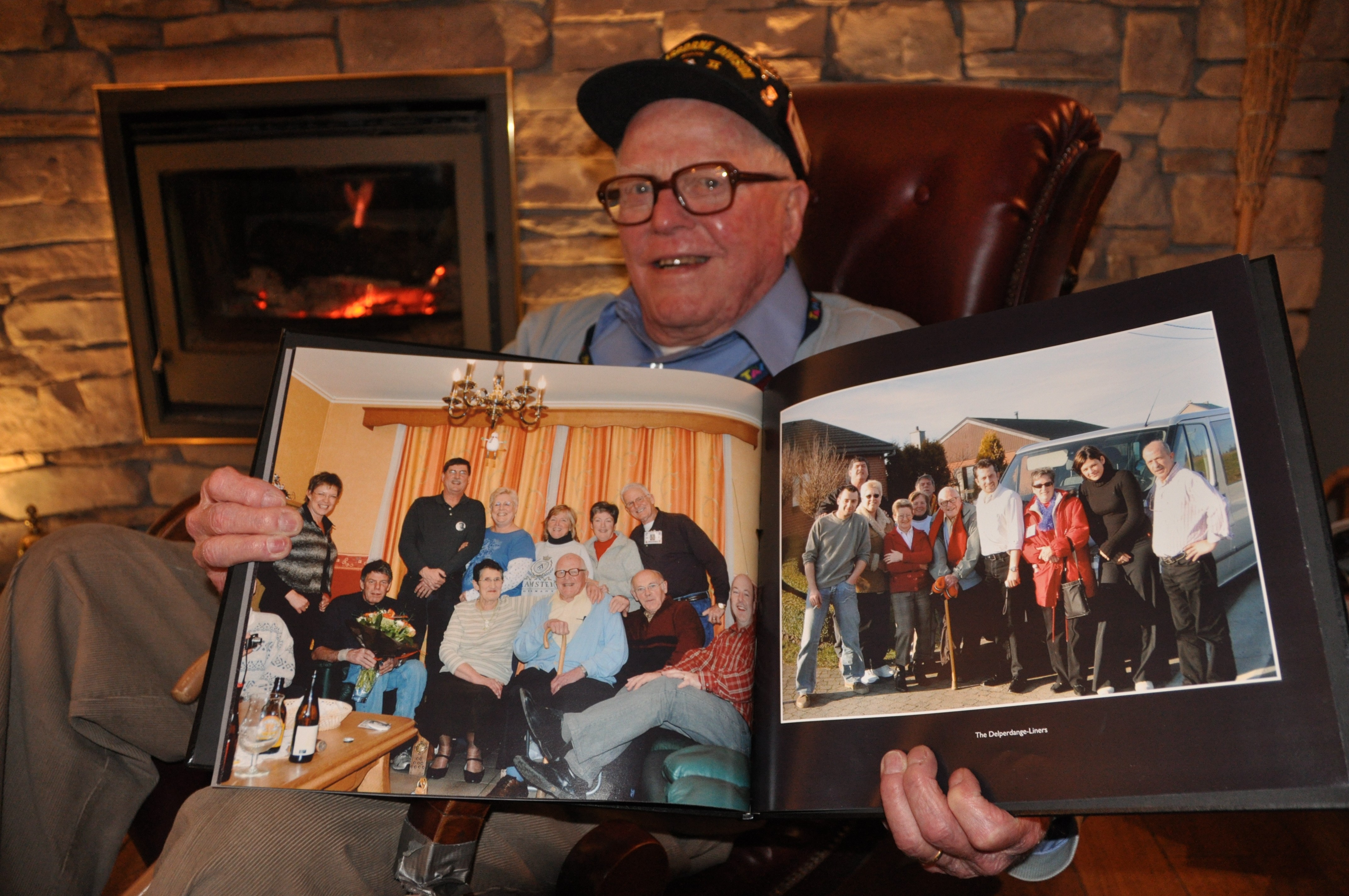

In town for the 65th anniversary of the Battle of the Bulge Dec. 12-13, Andrews again reconnected with members of the Leroy family. Though the parents have passed away through the years, Andrews developed a strong bond with the eldest daughter Elise, who was four during the war. Her husband, Jean-Marie Goebles, said through an interpreter that each time Andrews visits, the family learns more of their history.

"Elise was a very young girl during the war and doesn't remember much from that time," he said. "But when Red visits, we understand more about our life, our parents and the war. Our children learn about the war straight from a World War II veteran. It's a deep connection we share, and he is part of our family. We are very grateful for his sacrifices on our family's behalf. The more he comes back, the more special it becomes."

The family will always consider him a hero, he added.

Andrews demurely said every Soldier who fought in the battle should consider themselves a hero, especially the infantrymen.

"Most any Soldier in every unit should feel gratified that we accomplished the mission here, that we broke the back of the German offensive and altered the war," he said. "This battle gave all the GI's pride."

Andrews took part in the official ceremony Dec. 12 honoring the Allied forces' victory and sacrifices in Bastogne, laying a commemorative wreath at the base of the General Anthony Clement McAuliffe Monument along the parade route through town.

Social Sharing