CHIAfE+VRES, Belgium Aca,!" Inside a cramped brick farming shed in southern Belgium, 2nd Lt. Claude B. Cook had just fashioned an impromptu egg breakfast for his weary troops when he peeked his head above the windowsill after hearing a nearby firefight.

Within seconds he was dead.

Hit by a wayward .50 caliber bullet at that exact moment, he was one of 12 U.S. Soldiers killed during the first day of the liberation of Belgium Sept. 2, 1944.

The tiny brick building came to symbolize the sacrifices of all U.S. Servicemembers on the Belgian front in the eyes of the local residents, according to Belgian-American Foundation chairman and local historian Dr. Paul Delahaye.

"In this vicinity is where the first American Soldiers died that day," Delahaye said through an English translator. "If not for these troops, we would be speaking German today."

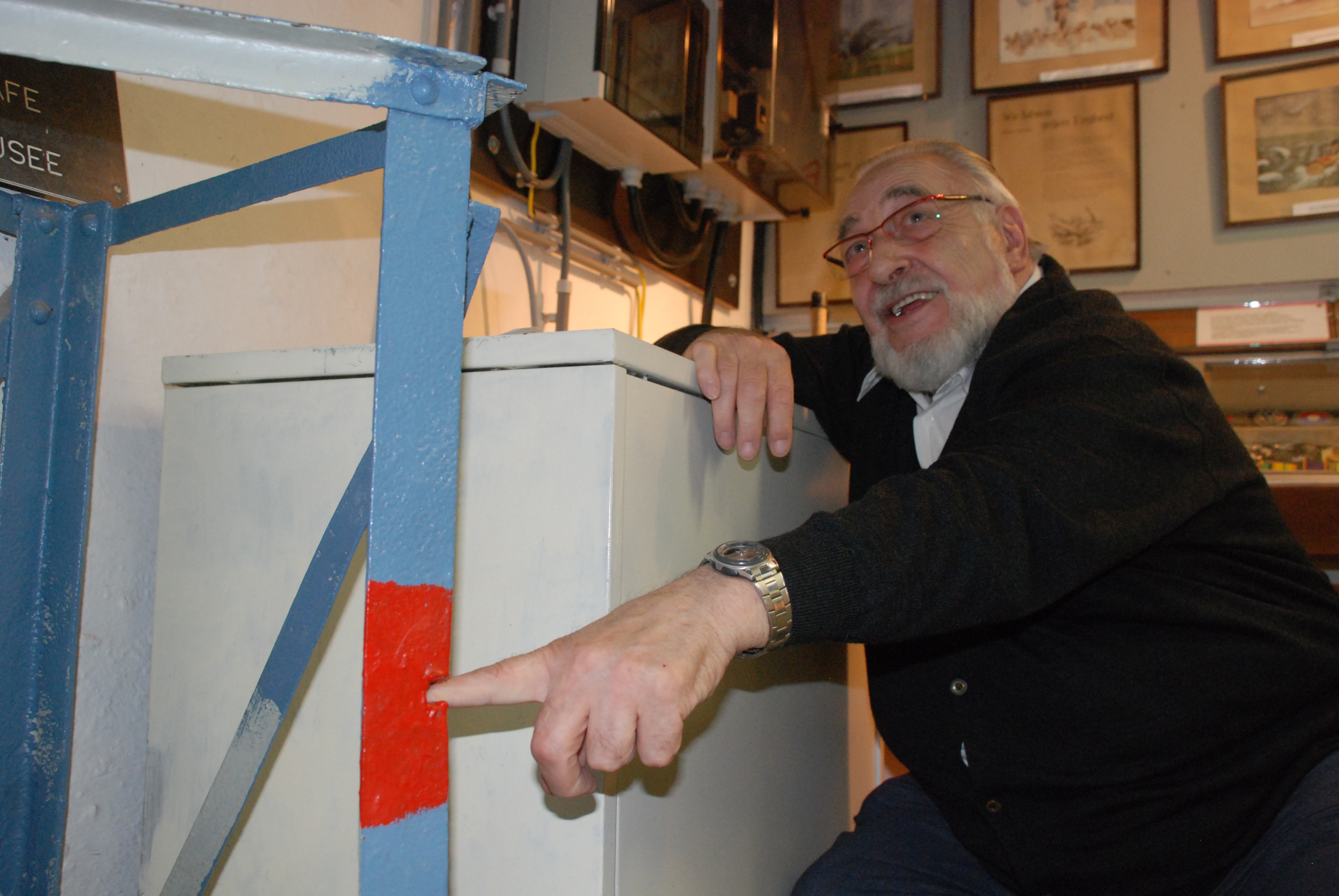

Delahaye refurbished the dilapidated shed into a museum in 1984 dedicated to the U.S. effort to liberate his country, replete with hundreds of pieces of memorabilia, ranging from German communication equipment to parts of Cook's mess kit.

It was but one step on what has become the Belgian's lifelong journey to honor American troops for their sacrifices in his homeland.

"We can never forget," he said. "We have a duty to honor these Soldiers. They died for the liberation of a country not their own, and for people they didn't know. We must continue to thank them."

In addition to the museum, called MusAfAe 40-44, Delahaye was instrumental in the creation of four monuments throughout his hometown province of Hainaut to honor Allied troops.

His plaque in Beauwelz pays tribute to the 39th Infantry Regiment, credited with liberating the village. Another memorial in Cendron, the first Belgian town liberated, depicts an angelic figure of liberty made of white stone unchaining a prisoner, while simultaneously stamping down the German aggressor. His monument in Macquenoise honors a B-17 crew whose bomber crashed nearby, and features the aircraft's propeller.

He also created a memorial to Canadian troops in his hometown of Momignies, recognizing their contribution to the Belgium's freedom.

Traversing the rolling hills and spacious farmland in between these memorials on a guided tour he is conducting, smiles spread easily across the retired veterinarian's large features accentuated by his crisp white beard. A vignette of WWII history plays out around each bend in the cornfield. Delahaye holds an encyclopedic knowledge of the war, recalling in an instant even the smallest details of the battle; from which farmhouse Cook and his troops borrowed their fresh eggs or the stump up the road on which the first U.S. Soldiers across the border briefly rested.

When the conversation turns to his childhood, wrought with harsh realities of war, wisps of smiles return periodically as if to lighten the weight of unbearable memories. To understand his deep appreciation for American troops is to understand the graphic horror he witnessed before his 10th birthday.

Delahaye was born Oct. 2, 1931 in Beauwelz, an area called the "boot of Hainaut," where the southern region of Belgium meets France. Before the end of the decade, war had settled into the boot. Piling their wagon full, his family sought refuge in Northern France along with the rest of the people from his village. The townspeople were soon forced to turn back, however, due to fighting near their intended settlement outside Dunkirk, France.

Along the return route through the Forest of Nouvion, young Delahaye witnessed the bloated bodies of those who fled the town just 12 hours after his family. German aircraft had sprayed the route with bullets while the Belgians fled their homes. He vividly recalls passing ditches filled with swollen dead horses and corpses lying in the road with discolored faces.

In June 1940, German troops rounded up intellectuals nearby to ensure Hitler's security in his bunker at BrAf"ly-de-Pesche. Delahaye stood motionless as the troops arrested his educator father at machine gun point while his pregnant mother stood by his sister in the hallway. His father would return home after a short while, but many others he knew were less fortunate.

"There was starvation and depravation all around," Delahaye recanted. "Prisoners would return home just to die. We were in a constant state of alert and anxiety."

In July and August of the same year, Delahaye remembers a disciplinary unit settling in at the Beauwelz entertainment center, nearby his home.

"Every evening, a belt party would occur," he said, in which 20, 50 or 100 lashes of a belt were doled out as discipline to the soldiers, depending on how disrespectful they had been to Hitler. "I had a first-hand account of fierce German discipline. During some particularly harsh punishment, I would hear screams at first and then nothing."

It was at that point he feared for his life, he said. If the Nazis treated their own that way, he thought, surely it would be worse for an outsider.

He was 13 years old at the time the Germans were forced out of his town, the first time he met Americans. He remembers it was precisely quarter to three on liberation day when an eccentric town priest rode his bike through the town proclaiming the arrival of U.S. troops.

"He was hollering, 'The Americans are coming, the Americans are coming!'" Delahaye exclaimed. "He was spreading the good word as a priest should."

What impressed him the most, he said, was the stark contrast in the attitude of the G.I.s to that of the strict German Nazis.

"The calm and relaxed demeanor of the Americans told me everything would be alright now," Delahaye said. "We knew we made it through."

That feeling made a lasting impression on him, he said, and became the driving force behind the creation of his memorials.

"After going through Hell for four years, I cannot describe the overwhelming joy everyone felt," Delahaye explained. "I thought to myself, 'This must be what heaven is like.' I set up the memorials because I wanted concrete reminders to make U.S. Soldiers' stories come alive. To me, it's a duty to honor these men for what they gave us. When living through those hard times, and then good times, there's no way to forget."

"I especially wanted the junior Soldiers to be remembered forever," he said.

One American who has visited Delahaye's memorials is 33-year Air Force veteran Stephen Michael, chief of Plans, Analysis and Integration Office for U.S. Army Garrison Benelux. After more than 20 minutes, describing the details of his personal tour and what he learned from Delahaye, Michael was overtaken by emotion while relating the depth of the Belgian's passion. He stopped abruptly several times near the end of his story, finishing his remaining sentences through tears.

"It is extremely humbling...," Michael said before pausing for a deep breath to compose himself, "... to know that someone from another nation has felt so spiritually moved to honor our troops for the last 65 years.

"I knew I couldn't talk about this without breaking down," he added.

Social Sharing