FROZEN legs, captivity during war, and a hunger-driven scramble to gather scattered pieces of bread on the ground are just some of the mental snapshots that William Schuchert still holds from his days as a young Soldier during World War II.

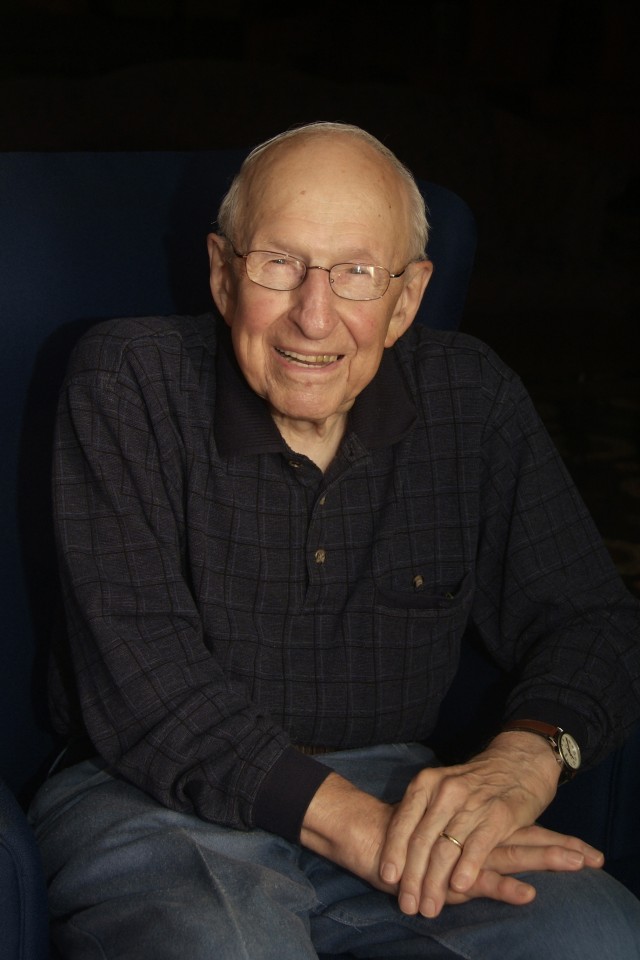

Because of medical problems caused by prolonged exposure to sub-zero temperatures in foxholes, Schuchert's legs were amputated below the knees six years ago. Today, the 85-year-old resident of Middletown, N.J., uses a cane and artificial limbs to maneuver.

As a young Soldier in Europe in 1944, Schuchert had already seen the Army medics twice to treat his frozen limbs. He was scheduled to see the medics a third time, but a significant event that day spoiled his plans.

Seeking to neutralize the advancing Allied forces, Adolph Hitler launched a major offensive thrust that came to be known as the Battle of the Bulge. As a member of the 28th Infantry Division, Schuchert and his fellow Soldiers were in the direct path of the surprise German assault that began at 5:30 a.m., Dec. 16, 1944.

Instead of seeing Army medics, Schuchert became a prisoner of war.

"We were one of the first ones they hit," he remembered. "They hit us, bypassed us and we were surrounded by all of the Germans. Our captain decided that it was better to surrender than to die."

Schuchert remembered the dire warning to Army prisoners from their captors. "The Germans used to tell us, 'If one escapes, we're going to shoot you all.'"

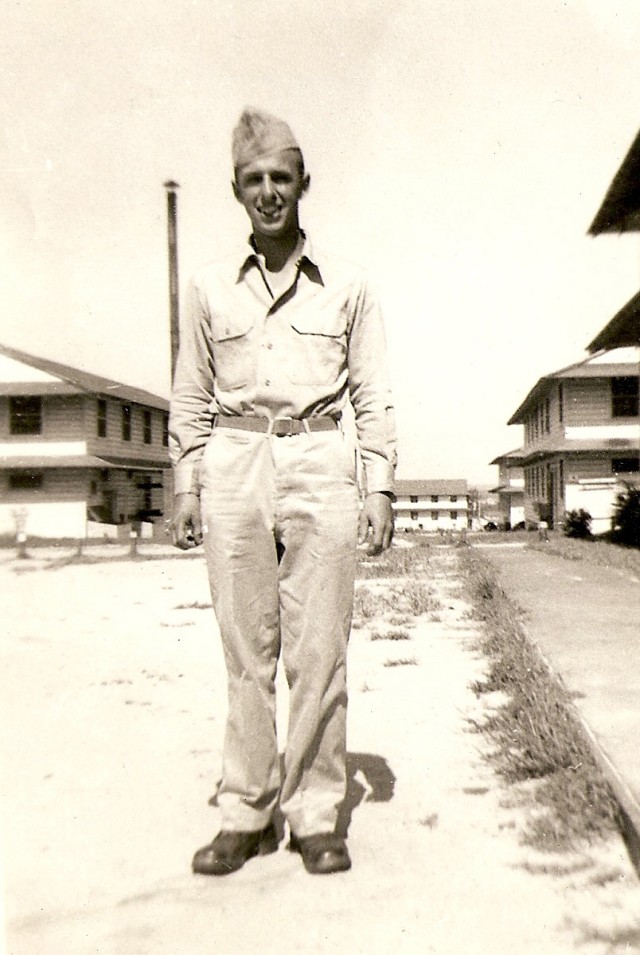

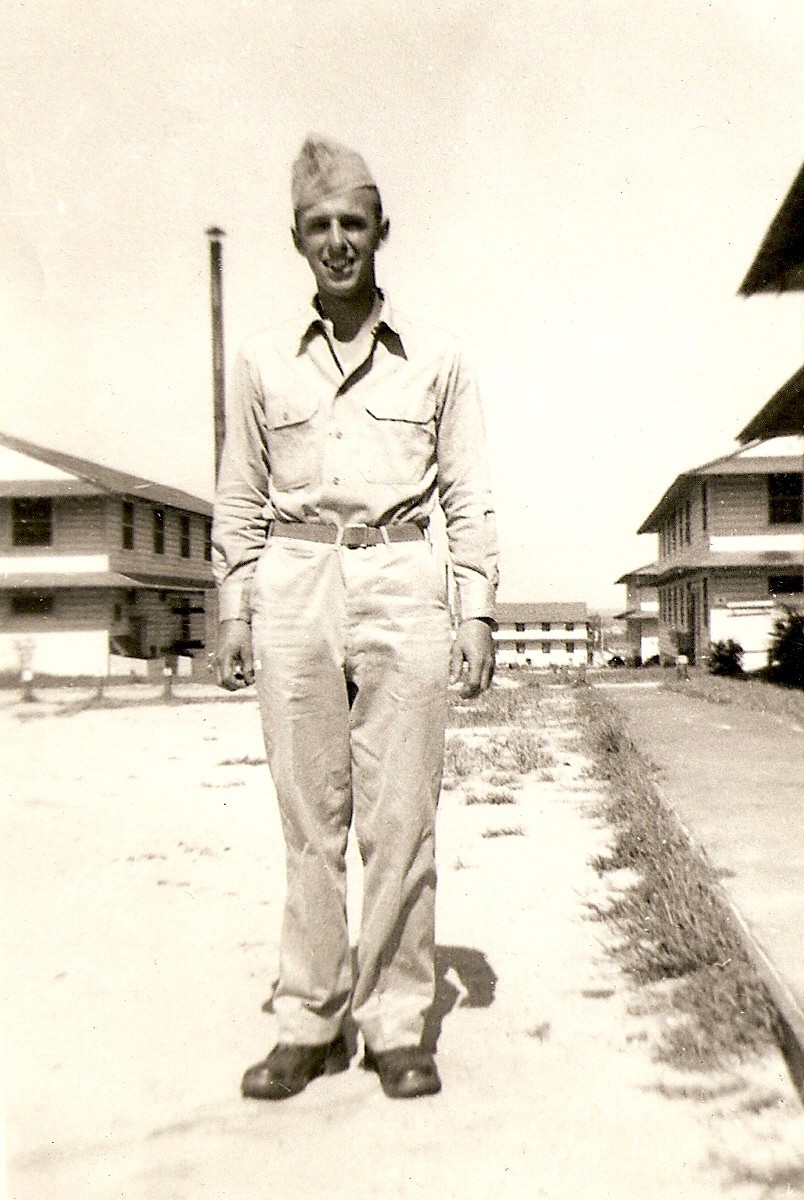

Originally from West Mifflin, Pa., southeast of Pittsburgh, Schuchert was drafted into the Army when he was 18 years old. His outfit, the 28th Infantry Division, was nicknamed the "Bloody Bucket" division because of the division's red, keystone-shaped insignia. It was also the Army division in the movie "When Trumpets Fade," about the battle in the Huertgen Forest.

Schuchert recounted his experiences recently after watching a theatrical play with a World War II-era theme staged at Brookdale Community College at Lincroft, N.J. This year is the 65th anniversary of D-Day, the storming of beaches by Allied forces in Normandy, France, to liberate mainland Europe from Nazi occupation.

Even before he was captured on the first day of the Battle of the Bulge, Schuchert had a variety of harrowing experiences when his division was deployed to the Huertgen Forest, located along the border between Belgium and Germany.

"The Germans used to shell us just about the time we were eating," he recalled with a laugh. "Just to make it so that we didn't get a warm meal."

Typically, there were about six men in each foxhole, which was covered with tree branches to protect the Soldiers from shrapnel and debris. "At night it would get about 30 to 40 degrees below zero," he said. "I had my feet frozen twice."

Because enemy shelling could be constant for six or seven days at a time, Soldiers were reluctant to leave their foxholes. Schuchert remembered that they would take turns leaving their shelter to fill the canteens of those who stayed in the foxhole.

"I went out one day to the usual place where we got water and saw three dead Germans in the water," Schuchert said.

"I went down further and found a place to fill up the canteens. I came back and was only about 20 feet away from the foxhole when the Germans started shelling. The shrapnel broke the wooden stock of my rifle in half and blew the top off my canteen."

Under such perilous conditions, the Soldiers quickly developed tight personal bonds. "A lot of us were roughly the same age," Schuchert said. "It didn't take long, because you're fighting alongside each other, to become close friends."

During the time that Schuchert was a prisoner of war, which lasted about four or five months, his most vivid memory was the relentless hunger among prisoners.

"We were hardly getting anything to eat," he said. "Maybe soup one day or bread."

Intense hunger at times drove men to steal food. "If you put something on the (prisoner barracks) stove and turned your back, it would be gone," he said. "I had that happen to me one time."

Schuchert spoke nonchalantly about such incidents, noting that many Americans today have never known constant, unyielding hunger.

"I figured that whoever took it (food) probably felt he was justified to get something to eat because he was starving or close to it," he said.

Schuchert remembers one time when he, himself, kept a sharp eye for an opportunity to supplement the meager rations of a prisoner.

One day the Germans gave each prisoner a fistful of bread before herding the captives onto a train. At one point, American and British aircraft strafed the train, sparking a mad scramble among prisoners to get off the train.

"Eventually, we got the train doors open," Schuchert remembered. In the ensuing chaos to bolt from the train, he noticed that the ground was littered with pieces of bread that the Germans had given the prisoners that morning.

He swept down to collect and eat as much bread as he could. "So I ate pretty good that day," Schuchert said.

As his days as a prisoner of war slipped by, Schuchert's morale would rise at times when sporadic clues suggested that he might live long enough to savor life outside the confines of guard towers and barbed wire.

"We used to try to get as much news as we could from the Germans," he said. "Some of them would leak to the Soldiers that things weren't going well for them. That made me think that I would eventually get out of there.

"When I was in England, it seemed that all the bombing was coming from Germany and here it was going the other way. That gave you a good feeling."

With the relentless push by the Allies into Germany, it was just a matter of time before the Germans who captured Schuchert and his fellow Soldiers realized that the war was lost.

"They made an arrangement to turn us back over to the Americans," Schuchert said. "That was one of the happiest days of my life."

Even after the war ended and Schuchert returned to the United States, he continued to have problems with his feet from chronic exposure in frigid foxholes.

"I used to always go to the foot doctor maybe every couple of months," he said. "Eventually, when I got to be 79 it got pretty bad. They took both my legs off below the knees and now I'm walking on artificial legs."

After Army life, Schuchert returned to Pennsylvania and obtained a college degree from Duquesne University in Pittsburgh.

Schuchert has grappled with the typical bumps and grinds of life over the years, yet his war experiences gave him an enduring perspective.

"When things looked bad, all I had to do was think back to the Battle of the Bulge, smile, and say, 'Nothing is as bad as that.'"

Social Sharing