There are many types of memories, and many ways to record them. Our lives are filled with the sounds, images and belongings of those we have met, befriended or lost. With the invention of the digital camera, we can now preserve in crisp, high-definition clarity every moment we desire. But there is something no camera can capture, no voice recorder can grasp: the essence of a person.

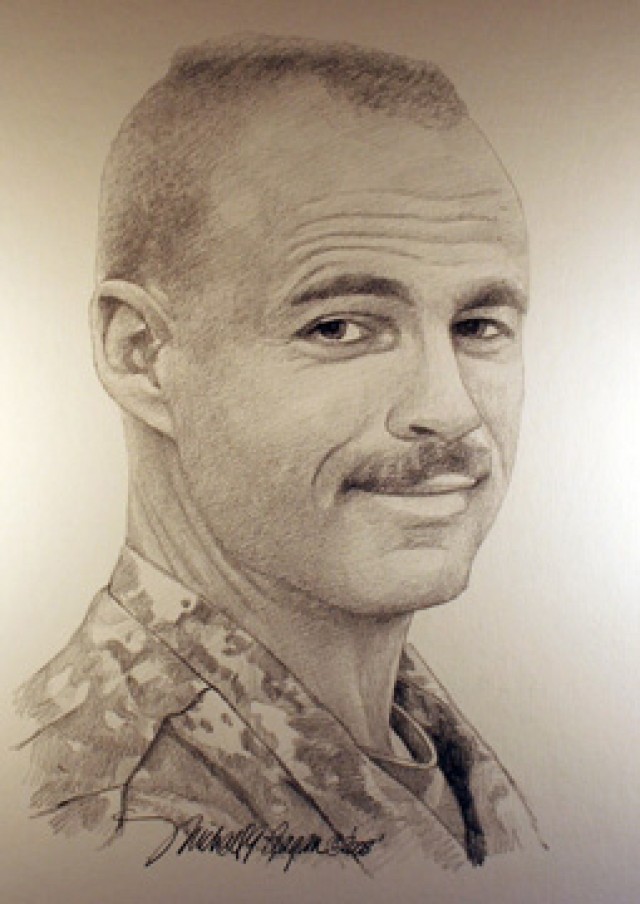

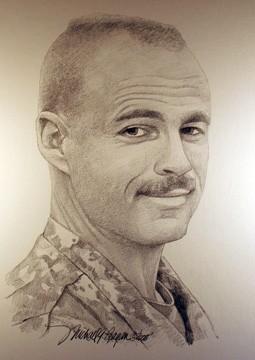

Michael Reagan, an artist based out of Seattle, provides free, hand-drawn portraits to families who have lost a loved one in the war on terror through the Fallen Heroes Project. His portraits have the ability to do what the camera cannot-capture and hold the spiritual aspect of the person depicted.

Eric Herzberg, a former Army captain, is one of many recipients of Reagan's work. Herzberg's son, a Marine, was killed in action in October 2006. After hearing about Reagan, Herzberg asked the artist to do a dual portrait of himself and his son.

"We had a personal connection right away-he's former military, I'm former military. But when I received the portrait that he drew of Eric and myself it was just so absolutely stunning," Herzberg said.

"I had a reaction I didn't expect because it meant way more to me than just the image on canvas, on art board, that he had been able to do. It was like there was a spiritual component to it, that, you know, he's bringing part of my son back to me and I was just always struck by that."

The connection that he and Reagan shared prompted Herzberg to offer his help about a year after receiving the portrait of his son, while visiting Seattle on a business trip. He discovered that Reagan had been operating all aspects of the project entirely on his own.

"So I said 'Michael, I don't know how you're even standing up after three years. You've got to be able to just do drawing and let someone else do the rest.' And he looked at me and said 'Well, who's going to do that'' And I said 'Well, you know, why don't you just let me take a crack at it. You don't know me very well-we just met. But you're going to find out that I'm a person that does what he says he's going to do,'" Herzberg explained.

Since then, Herzberg has helped organize and run the business aspects of the project. By working with the Fallen Heroes Project, he feels he is honoring his son's memory.

"It's been truly a blessing for me," Herzberg says. "This is more like therapy for me than anything else. If I wasn't helping him, I'd probably be doing something unhealthy to numb the pain or deal with the loss of my son."

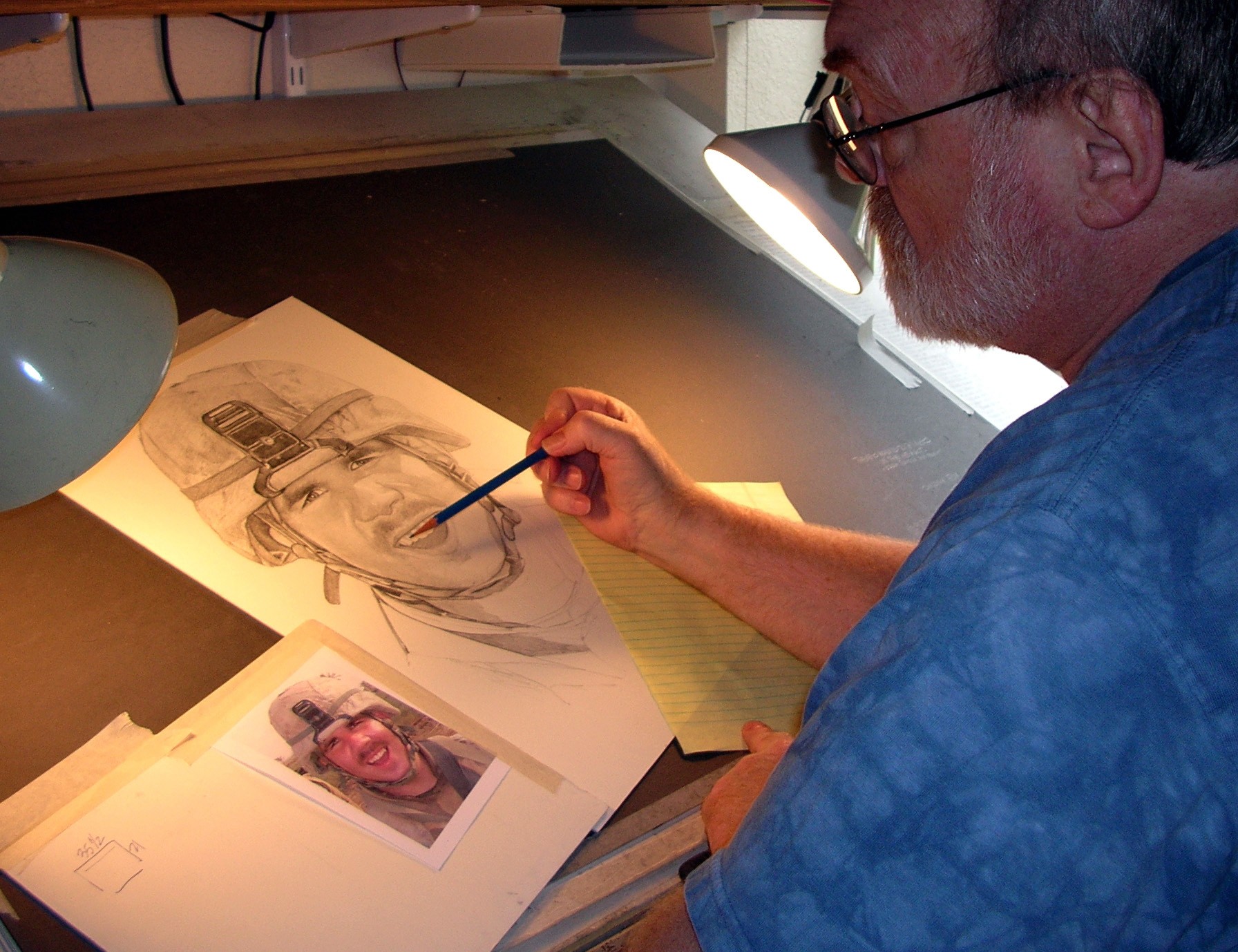

Reagan, a Vietnam combat veteran, drew celebrity portraits for 30 years, donating the proceeds to charity, prior to starting the Fallen Heroes Project. A nationwide news network aired a clip of him speaking about his portraits, and before he knew it, he had a request. A woman who saw the broadcast called him and asked if he could do a picture of a fallen Soldier-for free.

Unable to deny a fellow veteran, Reagan readily agreed to draw the portrait.

"To be real honest with you, I had no idea what it was about to do to my life," he said. When the woman received the portrait, she called Reagan to thank him. The woman had not slept through the night for a year, since her husband died in Iraq; the portrait allowed her to reconnect with her fallen hero, and she finally slept.

From that moment on, Reagan felt he was called to provide solace to the families of the fallen.

"I'm supposed to do this," he said.

The project has been distributing portraits for five years, and provides pictures for every branch of the military. To date, more than 1,600 portraits have been given away, all for free, including postage. He considers this project more important than his previous career as an artist.

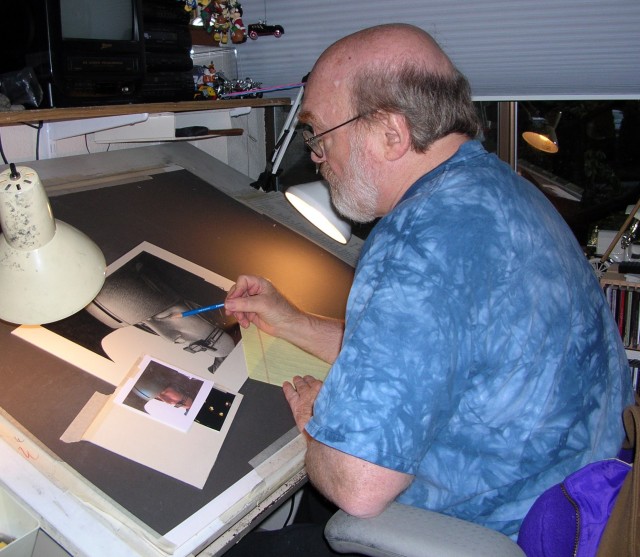

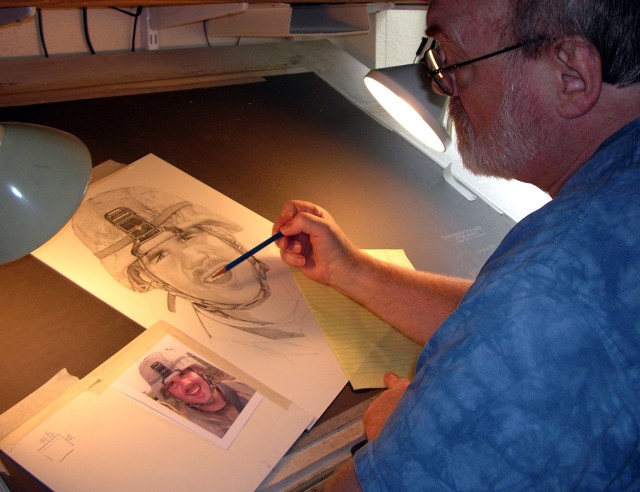

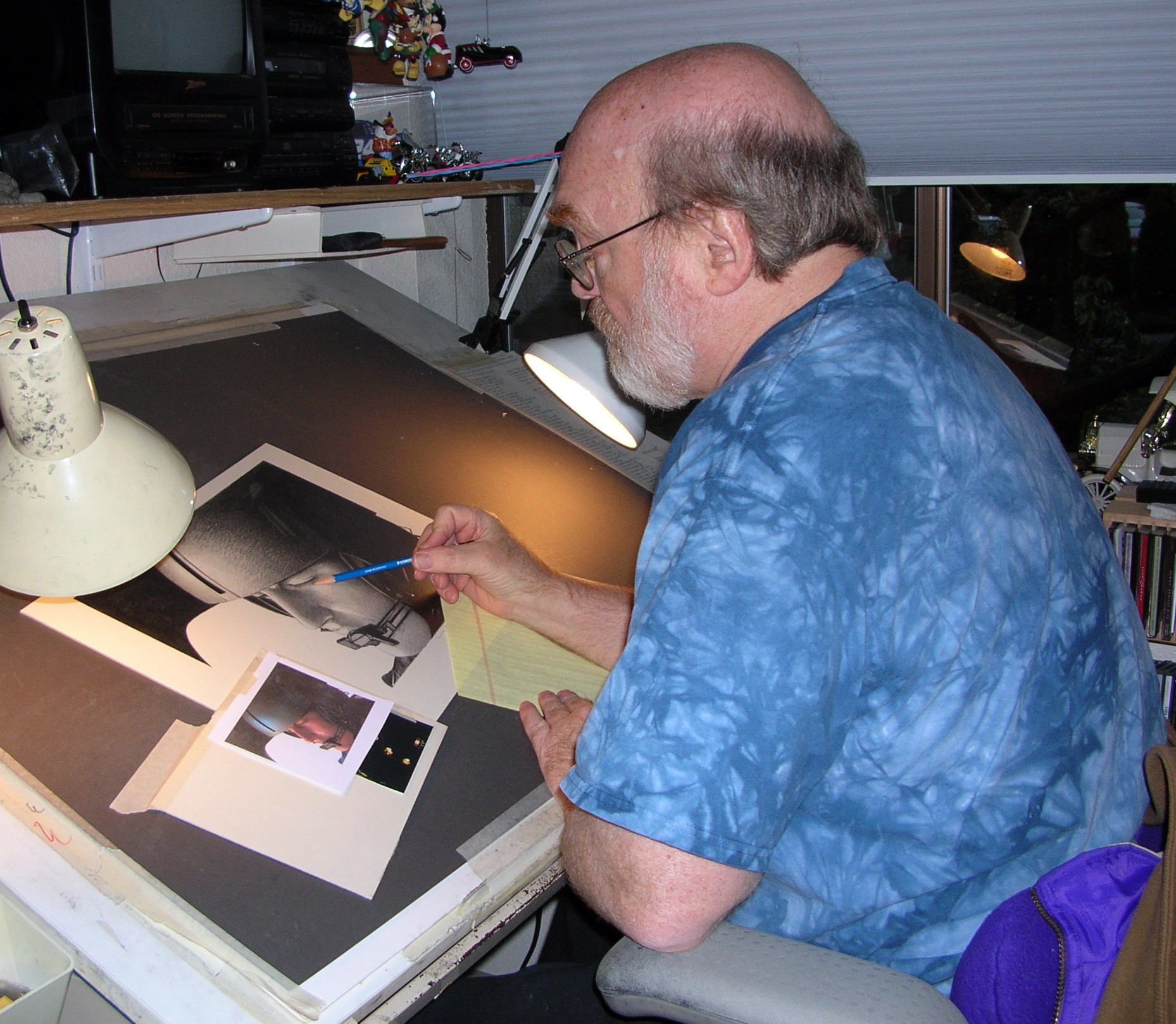

Reagan's work on the Fallen Heroes Project is a full-time job. It takes six hours to complete one portrait, and he finishes two a day, Herzberg said. The project is a 501(c) 3 non-profit organization, and as such, it is totally dependent on donations-Reagan receives no compensation except the thanks of grateful families. Art-supply manufacturers donate art board and pencils to help Reagan continue the project.

"You have a very talented man who has set aside his own life because his life now is doing these portraits, 12 hours a day, seven days a week. And he has essentially given up his life to draw those who have given up theirs," Herzberg said.

Once, Reagan had the dad of a fallen hero call and accuse him of getting something out of the project, though Reagan reiterated he was doing everything for free. The man insisted he was being rewarded.

"I got a little upset with him and said 'Well, no I'm not,'" Reagan recalled, "and he said 'Sure you are, Mike, you're getting to come home from Vietnam.' And he was right. I kept wondering what was happening to me, what was changing inside of me, and what was changing was after 40 years I was being able to come home. That's my reward."

"I didn't know I hadn't come home," Reagan added, but after completing the first portrait, something changed. Reagan said he was able to feel love in a different way.

Some families are skeptical at first, waiting for Reagan or the project to ask for money. But once they discover that these portraits are gifts and tributes to the fallen, the family is greatly relieved, Herzberg explained.

"This is more than the image of their fallen hero on art board. It's the idea that somebody could love them so much without ever having met them to give them a gift like this. And at some point that kindles some spark, whether its hope or faith or just the idea that there is goodness left when it seems that most of it has been stripped away," Herzberg said.

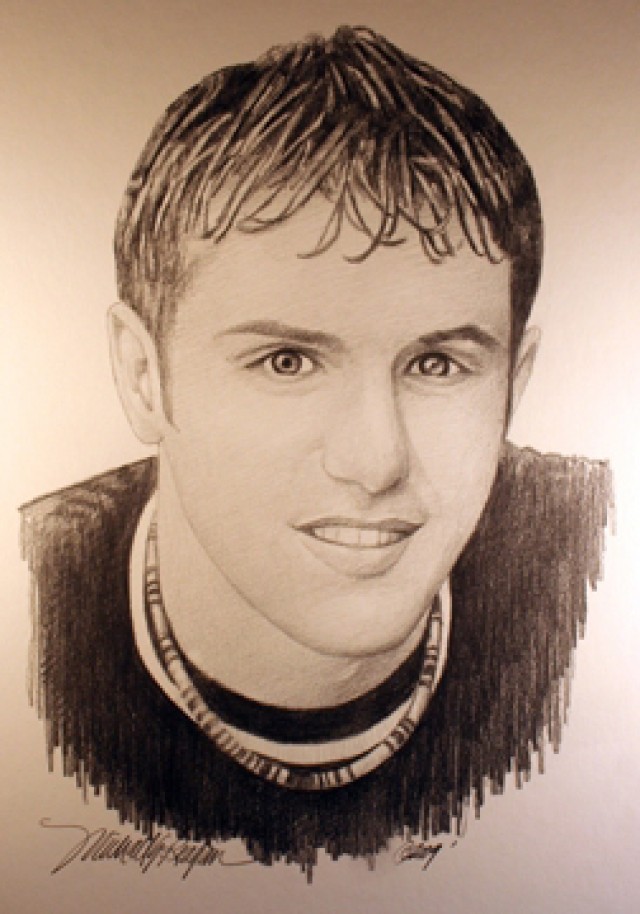

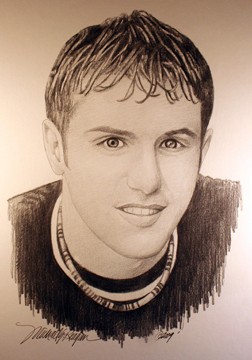

Gene and Eva Jo Stephens received a portrait of their son, Sgt. 1st Class John Scott Stephens, from Reagan and were stunned by the resemblance.

"I couldn't believe how much this picture looks like my son," Eva Jo said.

Scott, as his parents refer to him, was an Army medic for 21 years and loved his job.

"He was a medic, a combat medic. That's what he was doing when he got killed," Gene explained. Scott was touring the region training Iraqi medics. "He was killed making one of the tours."

Scott, who loved sports and frequently requested equipment for the children in areas he was stationed, started his career with a bang.

On his first assignment in Germany, Scott was undergoing on-the-job training when a young private got stuck in the breach of a gun and had his leg torn off, Gene recalled. Scott's supervisor panicked, and Scott jumped in and took care of the private. He saved his life.

"Scott's commanding officer wrote a letter telling us all about it and what a fine young lad he was. So apparently I'm not the only one that thinks he was a pretty good man."

The Stephens family finds great comfort in the portrait of their son. The picture hangs near the kitchen; Gene and Eva Jo pass it on a daily basis.

"This picture is so wonderful. Every time I look at it, it's like he's looking at me, telling me 'get with it mom,' like he always did," Eva Jo laughed.

Having the picture is "kind of like having him here," Gene added.

Reagan spends time getting to know every face that crosses his desk, paying careful attention to family descriptions and anecdotes. He believes that each portrait has some sort of message-he doesn't know what it is, but he knows when a family opens the package and sees the portrait, they will know.

"A lot of this is very spiritual to me, and beyond my understanding-but I don't need to understand," he said. Reagan explained that love drives him to continue the project, and gets him through the more difficult emotional aspects involved in the process.

"I need these people to understand that I appreciate them," Reagan emphasized. "I love and respect this loss and I will never forget" the sacrifice of the deceased, he said. The care he takes in creating a portrait and delivering it to a family is evident to most recipients.

"Mr. Reagan wrote us the nicest letter that came with this picture, (especially) not knowing my son, and he seems like a very great guy. He seems to care about other people, and that's hard to find much anymore," Eva Jo said.

Reagan hopes that this project will help heal the families of all those lost, as well as the country as a whole.

"The country has a broken heart-it's not just the families," he explained.

He estimates that 95 percent of the fallen from the war in Iraq could cross his desk eventually, and he'll be able to finally send them home.

If you would like to learn more about Michael Reagan and the Fallen Heroes Project please visit:

www.fallenheroesproject.org.

Social Sharing