FORT BRAGG, N.C. -- On January 23, 2018, the U.S. Army reached a historic milestone: one hundred years of dedicated psychological operations support to military and national security objectives.

Of course, the practice of using psychological tactics to influence foreign populations predated 1918. However, it was not until World War I that the U.S. waged the first orchestrated military propaganda campaign in its history, establishing two agencies specifically for that purpose.

The first agency was the Psychologic Subsection under MI-2, Military Intelligence Branch, Executive Division, War Department General Staff. The second was the Propaganda Section under G-2, General Headquarters, American Expeditionary Forces in France. Taken together, these two agencies introduced an American military propaganda capability.

Entering World War I in April 1917, the U.S. War Department had no capacity to conduct what is commonly known as psychological operations, or PSYOP, or what is doctrinally referred to today as Military Information Support Operations. On January 23, 1918, Maj. Charles H. Mason, head of MI-2 in the War Department Military Intelligence Branch, direct-commissioned Capt. Heber Blankenhorn straight from civilian life to establish and lead the Psychologic Subsection for the purpose of organizing "the implementation in combat of the psychologic factor in the strategic situation" -- quite a nebulous charter for the new officer.

President Woodrow Wilson vehemently opposed the idea of military-run propaganda, so Blankenhorn's low-key activities were initially limited to research and planning. He spent ensuing weeks walking the halls and knocking on doors throughout the War Department, trying to get support for his idea of waging "leaflet warfare" overseas in support of Gen. John J. Pershing's American Expeditionary Forces in France.

Having received little support for his concept, Blankenhorn bypassed several layers in his chain of command and secured a meeting with Secretary of War Newton D. Baker on June 21, 1918. At the meeting, Baker was surprisingly open to military propaganda. "I think we should do this," he said. "I give my approval to it right now, subject to one condition. The President has had some misapprehensions about this ... [but] I will take this matter up with him ... If I say nothing further, it's approved."

Blankenhorn interpreted Baker's words as a 'green light,' and obtained approval from Brig. Gen. Marlborough Churchill, head of the Military Intelligence Division, to recruit and deploy with a small team. With popular social commentator and New Republic editor Walter Lippmann as his deputy, Blankenhorn and his team deployed in July 1918 and reported to the G-2, GHQ, AEF.

The team, never numbering more than thirty assigned and attached officers and soldiers, went operational in August 1918 as the Propaganda Section, G-2, GHQ, AEF. The first concerted American venture into official military propaganda was entirely ad hoc. There was no established doctrine or standard operating procedures to follow; it was all on-the-job-training and trial and error.

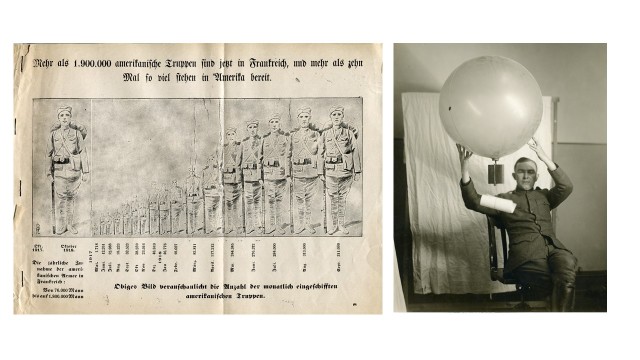

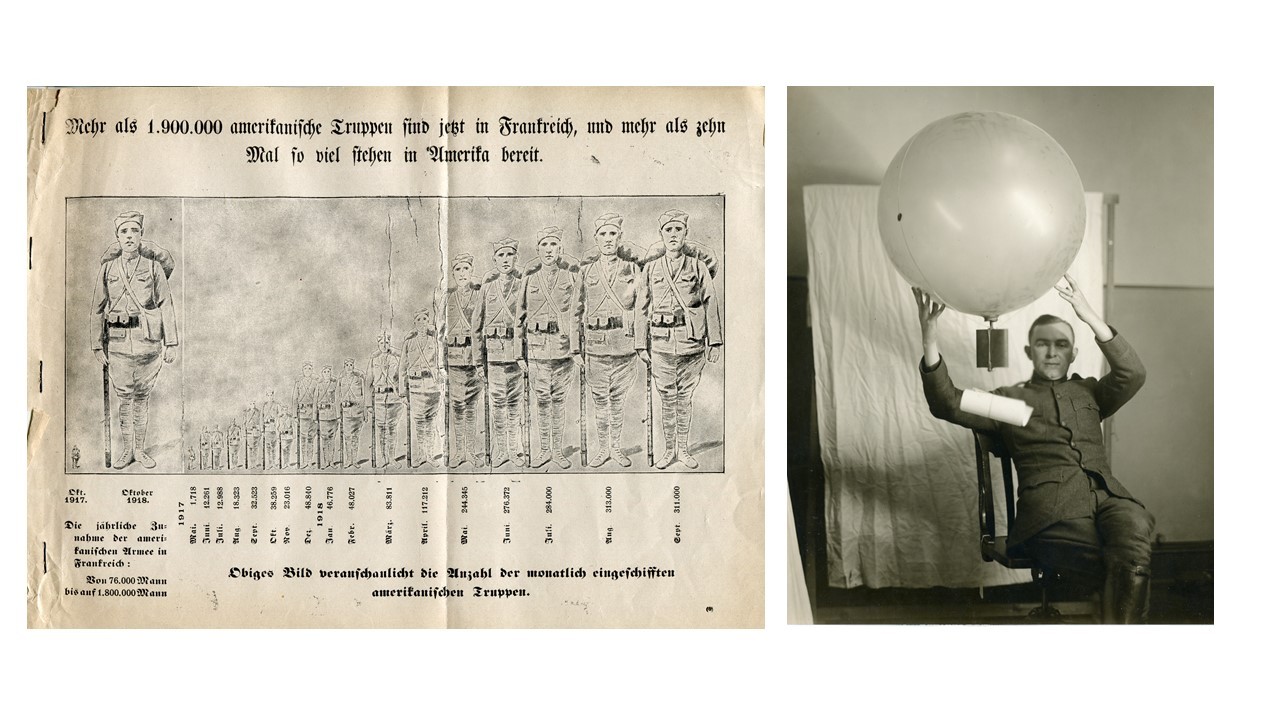

Between Aug. 28 and Nov. 11, 1918, the section printed some 5.1 million leaflets of eighteen different designs, and arranged to have more than 3 million of them disseminated, primarily by volunteering pilots and hydrogen balloons. Despite many challenges, it accomplished much for such a miniscule part of the two million-strong AEF.

Interrogations of German prisoners-of-war and statements of key German leaders after the war provided strong indication that U.S. and Allied PSYOP had contributed to the rapid erosion of morale and unit cohesion in the last months of the war. Unfortunately, the U.S. Army would have to re-learn many of these lessons during World War II and the Korean War, until it finally decided to retain a permanent psychological operations capability after the July 1953 Korean Armistice.

Even though U.S. Army PSYOP has existed since 1918, it did not become a formal regiment until Nov. 18, 1998 or a regular Army branch until Oct. 16, 2006. Moreover, the function has been known by many different names over the past century, including combat propaganda, psychological warfare, PSYOP, and most recently, Military Information Support Operations.

Although the terms, methods, media, situations, and target audiences have changed since January 1918, its fundamental purpose has not: "to convey selected information and indicators to foreign audiences to influence their emotions, motives, objective reasoning, and ultimately the behavior of foreign governments, organizations, groups, and individuals." With PSYOP units and soldiers continuing to support military, interagency, and partner nation efforts through the present day -- including recent successes against ISIS in Iraq and Syria and the Lord's Resistance Army in central Africa -- the PSYOP Regiment, and the nation it supports, has much to be proud of at this historic milestone.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Dr. Jared M. Tracy serves as the Psychological Operations Branch Historian, U.S. Army Special Operations Command. Tracy, a six-year veteran of the U.S. Army, earned a doctorate in history from Kansas State University and a Masters of Arts degree in history from Virginia Commonwealth University.

Social Sharing