Any military occupational specialty (MOS) 68W (health care specialist) noncommissioned officer (NCO) can tell you about Training Circular (TC) 8-800, Medical Education and Demonstration of Individual Competence. However, many of them have lost touch with the following statement from the TC's introduction: "To be effective, training must provide Soldier medics with opportunities to practice their skills in an operational environment. Conditions should be tough and realistic as well as physically and mentally challenging."

Often this type of training, a biennial requirement, becomes a watered-down, static exercise, devoid of the combination of environmental stressors and problem-solving required to create competent and confident medics. This is caused by a combination of factors, including lack of time, lack of training resources, lack of experienced subject matter experts, and complacency.

IMPROVING TRAINING

As the medical field becomes more technical, training requirements are sure to become more demanding. However, medics are a smart bunch who yearn for training and mentorship, and they will respond positively. Additionally, MOS 68W is unique in that it requires Soldiers to train to retain that MOS. If you have to do it, why not make it good?

FOCUS ON DYNAMIC TRAINING. Static training fills a purpose: it checks a box. But what inexperienced medics need is dynamic training preceded by phased cognitive and psychomotor exercises. This formula should be cyclical and follow a crawl-walk-run progression throughout the training year. This will keep skills fresh for more experienced medics and give leaders an opportunity to gauge the proficiency of junior medics who are new to the platoon.

Switch between classroom training (static) and lanes training (dynamic) to balance out your training plan, and keep the static psychomotor training to a minimum. It is not realistic and will create bad habits. Soldiers will never face situations like those presented in static skills stations, so why train with them? Medical emergencies are complex, evolving, and stress-evoking. They require problem-solving and the spontaneous development of contingency plans.

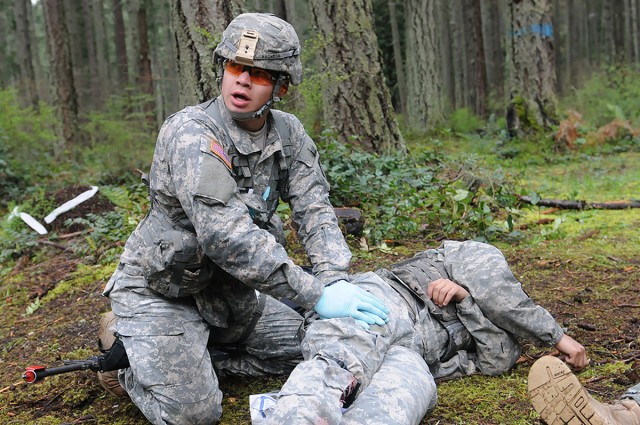

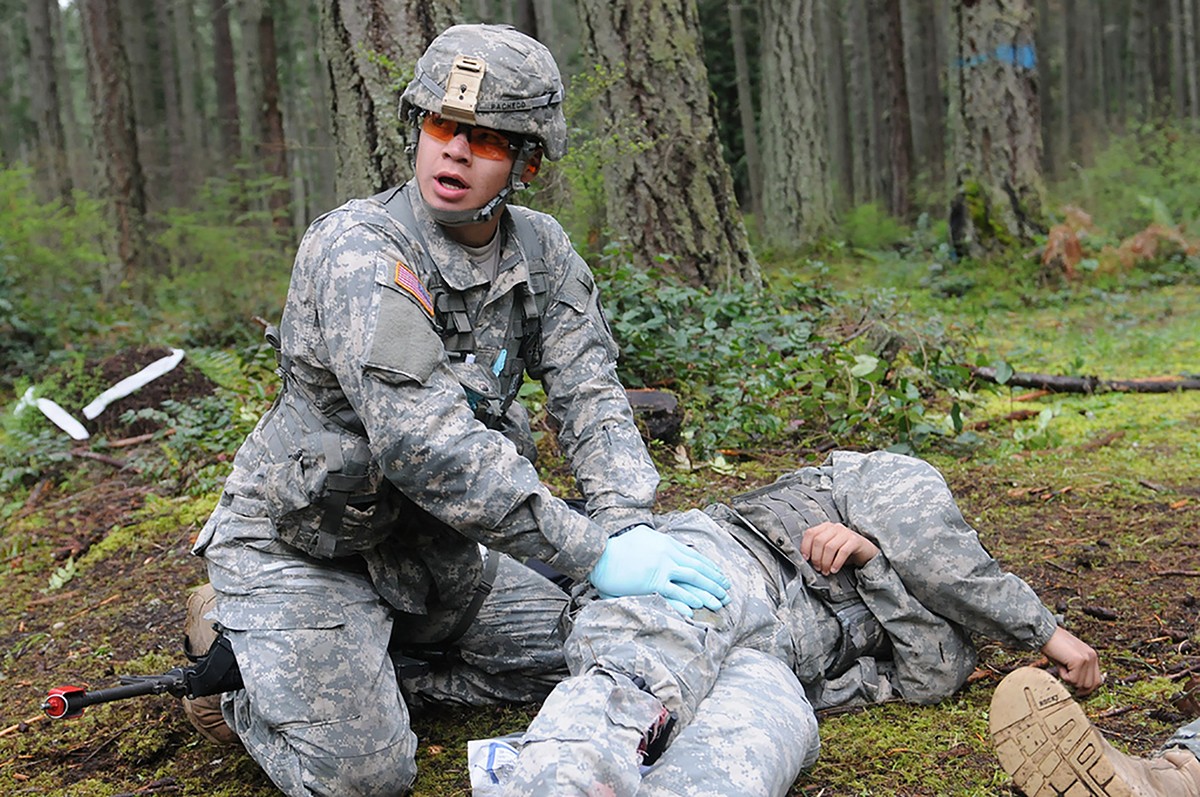

MAKE IT REALISTIC. Enlist Soldiers from other sections or companies to be the actors in training scenarios in order to eliminate familiarity. Use medical equipment as training aids to develop muscle memory. Do not be afraid to use moulage to add an element of realism. Training should be a mix of operational, sick call, and non-duty-related scenarios. TC 8-800 allows that flexibility.

KNOW THAT YOUR TRAINING PLAN WILL NOT GO TO WASTE. The continuous training requirements for medics, the combat lifesaver program, and warrior tasks and battle drills offer ample opportunity to improve the training plan and groom subordinates to assume more responsibility.

KEEP THE MEDICS INTERESTED. If you look out over your platoon and see glazed-over looks, yawns, and indifferent attitudes, your Soldiers are not learning. Training does not need to be fun, but fun training will always be remembered. And being remembered is certainly a hallmark of effective training.

SUCCESS UNDER STRESS

Succeeding in a stressful situation will build a medic's confidence and proficiency. The first time medics have a patient whose life is at stake should not be the first time they are stressed. They should be prepared for the rigors of emergency medical care, and it is their leader's job to prepare them. However, there are only two acceptable methods of preparation: experience and realistic training.

Experience comes with time, but leaders have direct control over their Soldiers' training. That training should include the most critical element to preparing for success under fire: stress. An outstanding resource on the benefits of adding stress to training is "Sharpening the Warrior's Edge," Bruce K. Siddle's book about the psychology and science of training.

Being a smooth operator under stress is not a trait that is inherent in all medics. Often, building confidence under stress is attained through successes and, conversely, through learning from failure during training. That learning comes from experienced NCOs constructively critiquing their Soldiers' performances.

However, Siddle states that a positive experience during dynamic training is required to develop confidence under stress. If medics are unable to perform positively during dynamic scenario training, static psychomotor exercises (skills stations) will benefit during remediation. Skills-station training allows trainers to slow down and isolate individual skills, which will allow them to better diagnose and correct problems. Siddle also states that the effectiveness of dynamic training deteriorates when the scenarios are neither realistic nor based upon actual field applications. A lack of realism leads to loss of confidence and motivation.

DON'T DO IT ALONE

Medical simulation training centers offer several medical training opportunities outside of the standard fare laid out in TC 8-800. Indeed, TC 8-800 does not mandate that medical education and demonstration of individual competence (or MEDIC) table training be conducted on a military installation.

When we think of community partnership, we generally think of the reserve component, but this does not need to be the case. What the 68W NCOs in the Army Reserve and National Guard lack in time to execute (compared to their active component brethren) they make up for in relationships with civilian medical agencies and training centers.

Consider "ride-alongs" with local fire departments and ambulance corps or rotations at the emergency department of a local trauma center. These offer opportunities for medics to witness and participate in stressful, complex, and educational experiences without being thrust into the role of a primary lifesaver.

In my experience, one of the most common complaints from subordinates has been a lack of training--more precisely, a lack of interesting training. Your unit's 68W training plan should prevent that complaint by providing realistic, challenging, and indelible training. It is about training good medics and--almost as importantly--it is about retention.

--------------------

Sgt. 1st Class Edward M. Erbland is the medical operations NCO for the 27th Infantry Brigade Combat Team, New York Army National Guard, in Syracuse, New York. He is a career firefighter, paramedic, and emergency medical technician instructor. He holds a bachelor's degree in criminal justice from the State University of New York College at Brockport and is a graduate of the Warrior Leader Course and Army Medical Department Advanced Leader Course.

--------------------

This article was published in the March-April 2017 issue of Army Sustainment magazine.

Related Links:

Discuss This Article in milSuite

Browse March-April 2017 Magazine

Army Sustainment Magazine Archives

Social Sharing