General Douglas MacArthur called them "My best Soldiers," during World War II, saying that the women serving in the Women's Army Corps worked harder, complained less and were better disciplined than many of his male Soldiers.

Born out of the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps in 1943, the WAC enabled women to take over more routine service and office jobs and free men for combat roles during World War II. Although disestablished in 1978, the WAC-and similar female components for other services and military nurse corps-was the only way women could serve their country. They often did so for less pay, limited advancement opportunities and flagrant harassment and disrespect from male counterparts.

WACs landed in France 38 days after D-Day and later served in both the Korean and Vietnam Wars, although women had to remain far behind the front lines. They weren't even considered "real" Soldiers. According to Chief Warrant Officer 5 Jennifer Redfern, a former WAC and now the Criminal Investigative Division's warrant officer career manager and counselor, they were "women servicemembers."

"I think that when the Women's Army Corps first started, that was the only way women could serve because society would not allow them to be full-fledged Soldiers. Of course, being a Soldier wasn't necessarily a long-term commitment. Society in those days expected women to be housekeepers and child rearers. But I think that...it's been pretty much accepted that we can do what everyone else does and still successfully raise children. I think that the Women's Army Corps allowed us to slowly demonstrate our abilities...to serve in the armed services as equals," she recalled.

While WACs worked long hours beside their male counterparts, they did so with training that was far different. Several women said they were disappointed at how easy physical training was during the WAC basic course. Retired Maj. M. Susan Windsich expected to complete low-crawls and difficult obstacle courses like the men. Instead, she was only expected to do exercises like modified push-ups, run either half a mile or in place and do a modified obstacle course called "run, dodge and jump," which involved running around fences and jumping over a small ditch.

"They would take us on marches in the hills around Fort McClellan, Ala.-a five-mile march, and at the end of it we would have grape juice and cookies. It was very, I guess, genteel...would be one way to describe it," said Maj. Gen. Mari K. Eder, deputy chief of the Army Reserve, who graduated in the second-to-last WAC Officer Orientation Course.

They even had makeup classes and were required to carry lipstick at all times, according to M. Isabelle Slifer, who retired from the Army Reserve as a lieutenant colonel. Blue eyeshadow, however, was forbidden, she said. Eder remembered the small regulation black bag that was almost useless for carrying anything but lipstick.

Retired Maj. Gen. Donna Dacier, recently the commander of the 311th Command and the G-6 (Communications) for U.S. Army Pacific, agreed that it was similar to finishing school, but added that the overall education about the Army's history, customs and courtesies was top-notch.

Nothing, she and other WACs said, beat the PT uniform, which consisted not only of a blouse and shorts, but also a wrap-around skirt that had to be worn over the shorts until WACs made it to the field.

"It was some guy's bright idea...totally inadequate for the type of physical-fitness training Soldiers would have," said Dacier.

The field uniform wasn't much better, with snug pants that buttoned up over the hips. The field boots-they were never referred to as combat boots because that would imply women could go to combat-didn't have any traction on the bottom so the WACs tended to slip and slide when participating in any exercises. According to Slifer, a WAC company commander had to show their commanding general the bottom of their boots before their footgear changed.

The class-A equivalent, known as "cords," was heavily starched. They looked nice, said Slifer, but keeping them wrinkle-free was difficult. Eder remembered traveling to her WAC graduation kneeling backwards on the bus seats, because their leaders didn't want the WACs' uniforms to wrinkle.

As the draft ended in 1978, the Army could not sustain an all-volunteer force solely with male recruits, according to Windisch, so women became more important. Change came throughout the mid-1970s, the WACs said, and they were gradually allowed to participate in things like M-16 rifle training, and began attending branch schools and officer-candidate school with male Soldiers.

Their reception was mixed. As ------Dacier pointed out, many of their classmates had gone to coeducational universities and were used to being around women. Some of the older Soldiers, however, either resented the women or harassed them. Slifer said she was often asked what she was doing there, and was told that she was taking the place of a man.

"I had a good time most of the time," said Windisch. "There were some real idiots-I'm being very nice-and there were some really wonderful people. We all got hit on back in those days a lot.

"For example, we were waiting for a ceremony in the colonel's office. I sat down on a chair...and the lieutenant colonel came in and plopped himself down on my lap. He said, 'So honey, do you come here often''"

Until 1973, if a WAC was married, her husband did not receive the same benefits as a military wife did, such as commissary and exchange privileges. And if she became pregnant, she had to get out of the military. Redfern joined a group of women who were petitioning to be able to remain in the military while pregnant and after giving birth. Even after they won the fight in 1975, Redfern said some people still tried to convince her to put her baby up for adoption. Later, when she decided to get remarried to a fellow Soldier, she was first told she would have to leave the Army.

Windisch had transitioned to the Army Reserve by the time she became pregnant and was surprised to find that she had to make her own uniform.

"There were no uniforms for maternity. So, I bought a pair of green slacks and a pretty flowered green blouse and wore that every day as my maternity uniform. They said, 'You can't fit into your fatigues, what are you going to do'' I said, 'Well, I've got this,'" she said.

The disestablishment of the WAC in 1978 was not without its hiccups. No one knew when they joined that they would eventually serve in the regular Army, and with excitement came nostalgia, a sense of a great tradition ending. The WACs would have to compete against male Soldiers who had varied experiences and more military schooling for promotions and choice assignments. The older WACs, said Dacier, were particularly "irritated" about the end of the WAC because they were losing their power base.

"So it was exciting for us and they really didn't like how enthusiastic we were about being able to take Pallas Athena off and put on our branch insignia," she said, describing how women could fully join different branches once the WAC was disestablished. Previously, women had been detailed to the Signal Corps or the Military Police Corps or other branches without being full members. They had separate companies, barracks, everything.

"When you go through basic training, you get pumped up because that's part of their job, to get you excited about what you're doing," said Redfern.

"So I was all pumped up about wearing the Goddess of Athena brass. But when working with my male counterparts as an MP, they were wearing crossed pistols and the women were still wearing the Goddess Athena.

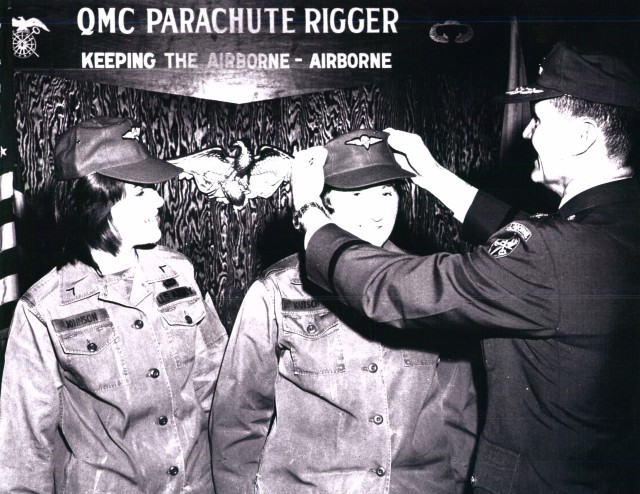

"So the day that we were integrated into the MP Corps...they had all three of us step forward in front of the formation and the platoon sergeant and company commander came up and they took our Goddess Athena brass off and put crossed pistols on us.

"I didn't think it would be any big deal, but it was. I was really excited because now I was a Soldier. I was very proud to be a WAC, but I was equally proud to be integrated within the Army itself."

Gwendolyn Hendly, who retired from the Army Medical Corps in the 1980s as a staff sergeant, said that even by that time personnel staffs weren't used to women retiring and she was listed as male on all of her paperwork. "When I retired...the guy told me he had never seen a woman come through before to retire."

For Hendly and the others who persevered, the Army turned out to be tremendously rewarding and somewhat humbling, as other women Soldiers now look to them as examples. Both Eder and Dacier said they expected to remain in the Army a few years, never that they would become generals. "I remember going to the dry cleaners and picking up my uniforms with that star on it," said Dacier. "I didn't feel like it was me picking up my own uniform. I felt like I was somebody else who was running an errand...because it was hard for me to fathom that that name tape and that star were linked together," said Dacier.

"I have been both honored and awed to have been a part of history, even if in a small way," said Eder. "I never thought I would be here at this place and time in my life, and wearing this rank...I believe you pay it forward and are obligated to help others in the same way."

Ask these women about the WAC, and they talk about how wonderful it was, in spite of the challenges and prejudices they faced.

"When I look back, I realize we broke down a lot of barriers we didn't even realize were there," said Windisch. "We just put our heads down, did work, kept moving and earned respect.

"The women with whom I worked, they are friends I've taken through my whole life. I think that's part of being a Soldier anyway, but being part of the Women's Army Corps makes it even tighter," Windisch added. "Any time another WAC sees the Pallas Athena on your lapel...you're already friends. You already know each other even if you've never met before."

Social Sharing