HUNTSVILLE, Ala. -- They are a symbol of the nation's military strength -- fast, powerful, threatening and, when needed, deadly.

But helicopters are much more than that to the Army aviators who fly them both in peacetime and at war.

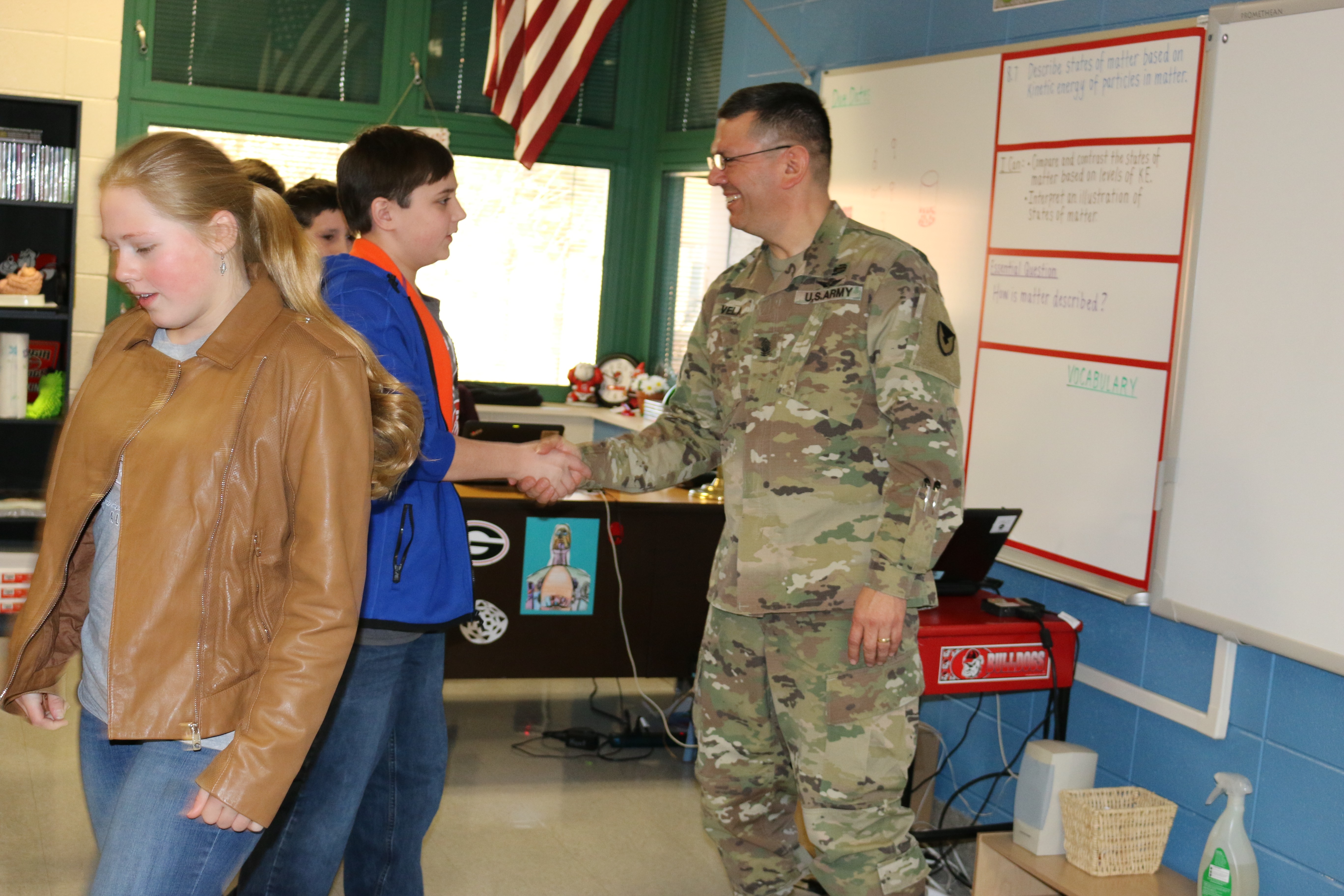

That was the message Command Sgt. Maj. Glen Vela of the Aviation and Missile Command took to the classroom Jan. 19 when he spoke to advanced science students at Challenger Middle School who are studying a curriculum on Flight and Space. He was invited to speak to the students by teacher Barbara Hunt.

Tracing the history of the Army's transportation needs -- starting with the cavalry; shifting to trucks, tanks, mechanized vehicles and aircraft in the early 1990s; adding jeeps in the 1940s; and then growing to include helicopters during the Vietnam War -- Vela said rotary wing aircraft quickly became the answer for missions that required speed and maneuverability.

"In Vietnam, helicopters on the battlefield allowed us to get in and out quickly," he said. "That was a new capability in the '60s and '70s. We now had ways to get Soldiers -- and especially injured Soldiers -- off the battlefield quickly."

During his 31 years as a Soldier, Vela has been assigned to Army aviation, first working as a mechanic and then as a crew chief. Before coming to AMCOM, he served more than five years as an aviation brigade command sergeant major for the 166th Aviation Brigade and 1st Air Cavalry Brigade at Fort Hood, Texas. His deployments include Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2001 and then again in 2006-08 and 2009-10, and Operation Enduring Freedom in 2011-12.

Vela outlined for the Challenger students the different missions of the Army's three main helicopters -- the Black Hawk, which is a medium-lift "cargo catch all" moving troops and supplies in theater and serving as the Army's ambulance with a top speed of 183 miles per hour and an altitude of 19,000 feet; the Chinook, the Army's heavy-lift "workhorse" able to transport as many as 55 Soldiers or 10 tons of freight at speeds up to 170 knots (196 miles per hour) and an altitude of upwards of 14,000 feet; the Apache, an attack helicopter where pilots, who sit front to back rather than side by side, can fly at a speed of 182 miles per hour and an altitude of 21,000 feet.

"The back pilot flies and works the radar, and the front pilot shoots and looks for targets," explained Vela, who has flown in an Apache. "It's very cool. It's everything you would think it to be and more."

Crew chiefs don't fly Apaches, as it only has room for two pilots. They do, however, fly with both Chinooks and Black Hawks.

"Crew chiefs do everything from washing the windows to changing the engine and everything in between," he said.

Vela said helicopters are limited in altitude because of the need of oxygen for the engines, which "start starving for air." Pilots can manage in extreme high altitudes thanks to a device nicknamed the "baby scuba tank" that is attached to their vests and that automatically connects to a pilot's nose to help them breath once they go beyond 6,000 or 7,000 feet in altitude.

Vela served as a Cobra crew chief in the earlier part of his career before that helicopter was phased out and he was reassigned to Apache. He has also served as a crew chief on the Black Hawk and Chinook. He has about 400 combat hours in Iraq as a door gunner, and another 200 combat hours in Afghanistan as a door gunner.

During his presentation, Vela recruited eighth grader Caden Hearn to demonstrate an Army pilot's flight vest and helmet. He showed the students a pilot's survival gear -- including a fire starter and tourniquet -- and utility pouch. When fully equipped, the vest weighs 70 to 80 pounds. Vela also showed the students the "Darth Vader" shield of his helmet, which protects pilots from fire and wind. Vela's helmet includes the signature of Lt. Col. Bruce Crandall, a Medal of Honor recipient whose story was told in the movie "We Were Soldiers Once … And Young."

New technology has always been part of the Army helicopter story, Vela said, and will continue to be so as the middle school students he spoke to grow up and begin their own careers. In the years to come, Army aviation will take on a new look with helicopters designed under the Future Vertical Lift concept, which will take off like helicopters and fly like airplanes. Likewise, unmanned aircraft vehicles will continue to reshape the future of Army aviation as they partner with helicopters on missions or take on missions of their own with their pilots driving from a safe location on the ground.

One constant challenge in the development of new helicopter technology, Vela said, is the limited amount of time helicopters can remain in flight. They only carry enough fuel to fly for two to two and a half hours.

"And that amount of time is cut shorter when a helicopter is hovering, or flying up and down mountains. That takes a whole lot more fuel," he said.

Other challenges are environmental threats, such as brown outs (sand and dust) and white outs (snow).

"Flying an Army helicopter is very demanding and very dangerous. You can't just have anybody be a pilot or a crew chief. You are tested very year -- during your birthday month -- to make sure you know what it takes to fly a helicopter," Vela said.

And, with that message it was clear to the students -- learning, studying and testing doesn't end with traditional schooling. They continue well beyond school as students take on careers. And the more dangerous the career, the more learning and testing are required.

Social Sharing