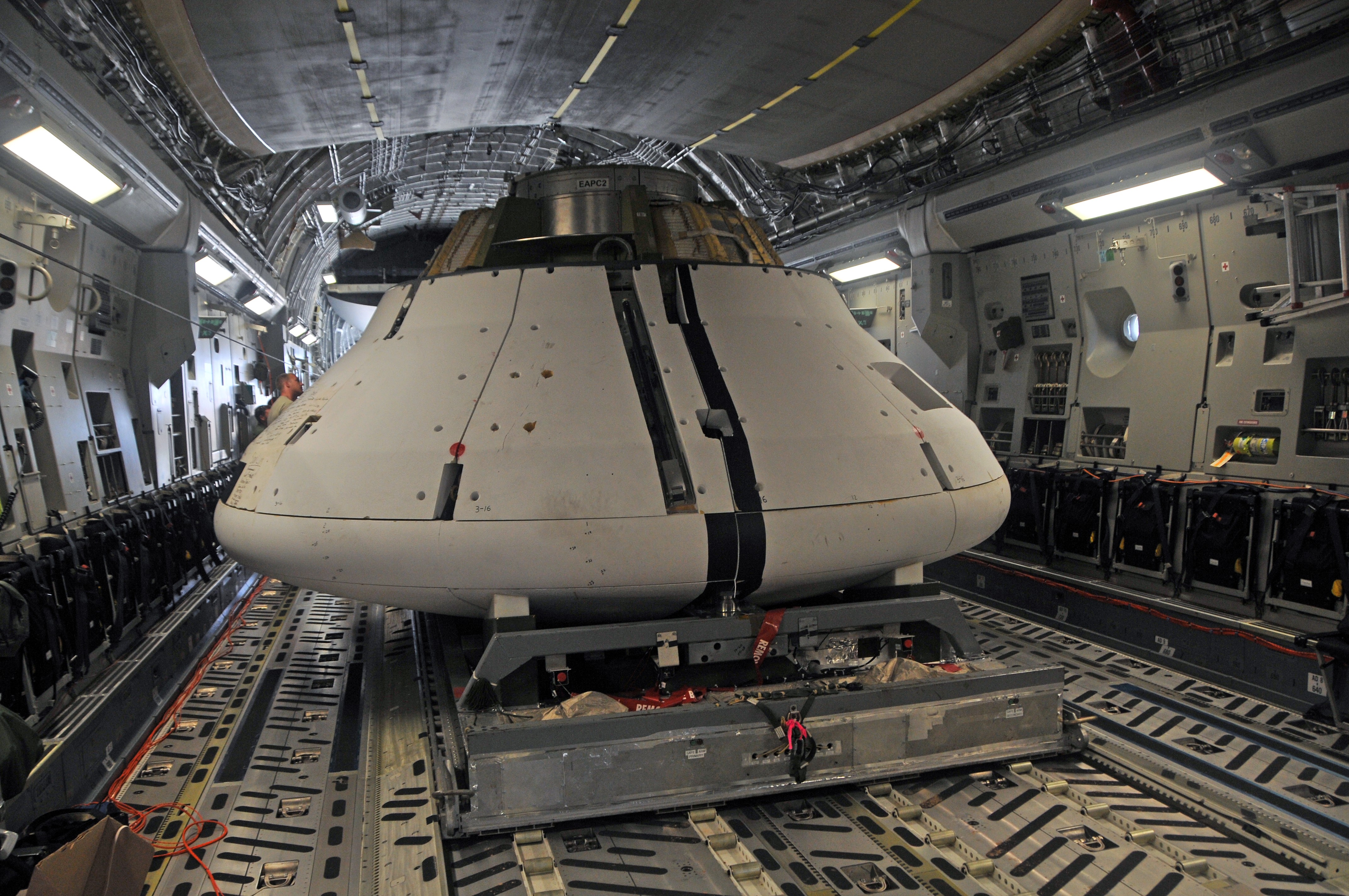

capsule waits inside the cargo bay of a C-130 for a drop onto an isolated range at U.S. Army Yuma Proving Ground. The Orion capsule typically has three main parachutes to land... VIEW ORIGINAL

U.S. ARMY YUMA PROVING GROUND, AZ-- The nearly-full sized model of the Orion space capsule was in the cargo bay of a C-17 flying 35,000 feet over one of YPG's isolated drop zones, but at least part of one observer's attention was far away.

"The 2030s will see the first humans walking on the surface of Mars," said Doug Wheelock, astronaut. "NASA usually picks astronauts in their 30s, which means the first Mars walkers are in the school system somewhere. That is very exciting."

NASA envisions humans returning to the moon and proceeding to Mars aboard the Orion, a feat that involves enormous quantities of power, endurance and speed. Escaping Earth's gravitational pull alone requires a speed in excess of 25,000 miles per hour, yet perhaps the most important aspect of human space travel --returning to Earth to tell the tale-- involves speeds less than one thousandth of that figure.

The astronauts aboard the Orion capsule count on the Capsule Parachute Assembly System (CPAS) to land them safely back on Earth. Each of the system's three main parachutes have canopies made with 10,000 square feet of broadcloth nylon, and the rope that makes up the parachutes' cord is made of Kevlar, the strong synthetic fiber used in body armor. The CPAS system is designed to deploy sequentially and pass through two stages prior to being fully open: after hurtling back into Earth's atmosphere, two drogue parachutes deploy to slow the 10-ton capsule prior to main parachutes decelerating the capsule to less than 20 miles per hour. The system is designed with redundancies meant to protect the safe landing of astronauts even if two parachutes fail.

"The chances of losing a chute are pretty low, but that low chance has pretty serious potential consequences if it happens" said Stuart McClung, Orion Crew Module Landing and Recovery System Functional Area Manager. "Gravity doesn't take a vacation."

In the most recent test at YPG, engineers sought to verify that the CPAS could decelerate the capsule to a safe landing speed even if one drogue and one main parachute failed to deploy, one of the riskier tests performed on the system. There were many factors to consider in such testing: for example, how much would the extra mass on the body of the craft from the two undeployed parachutes impact its stability in descent?

"From a structural design standpoint we didn't expect it would be an issue, but every time you test, you have the chance of learning something,. said McClung.

Given that the Orion capsule and CPAS system had a successful first flight in outer space last December, some folks may assume that this test was anticlimactic. NASA engineers, however, say this is not at all the case: in addition to being able to outfit the test vehicle with far more instrumentation and cameras than would be possible if it was coming from space, testing over land at YPG makes recovery and examination of the parachutes easier than when it lands in the ocean, as in a real space mission.

"We get so much data from these tests that it takes us months to process," said Michele Parker, deputy project manager. "We do a reconstruction where we know the position of these parachutes every millisecond of its descent."

Once the drop was completed, personnel fanned out and carefully recovered the massive deployed parachutes and lines from the desert floor. The Southwestern desert's summer heat was sweltering, but the workers gathered the fabric slowly and methodically: testers want to evaluate any damage that may have occurred to the parachutes, and know that it was not incurred from the recovery efforts. As the packed parachutes made the journey back to the Air Delivery Complex, where the parachutes were suspended from a high ceiling and carefully studied, workers from YPG's motor pool used a large crane to lift the massive test capsule onto a lowboy trailer for transport back to Yuma.

The prospect of humans landing on Mars and its moons entices the imagination, but space travel veterans are quick to remind their Earth-bound fellows that the effort involves far more than extra-planetary strolls for a select few.

"The biggest objective isn't setting foot on Mars--that's just the icing on the cake," said Wheelock. "The objective is all we will learn in the intervening years about science, technology, engineering, our planet, and ourselves. We will inspire generations of engineers: all of these things are part of the riches and rewards we will reap in coming years."

Social Sharing