"Unified Combatant Commands," "Joint Commands," and "Combined Commands" are effective arrangements for commanding all American forces and even Allied forces in Theaters of Operations or Areas of Responsibility. For America, this beneficial approach of a single commanding officer began barely ninety years ago. The U.S. Army reluctantly entered such arrangements with Allied armies in 1918. Unified, Joint, and Combined Commands became standard during World War II and have continued since then. The 1986 Goldwater-Nichols reforms streamlined such arrangements. Resulting success since 1989 is clear.

American forces succeeded before 1918 -- but did so almost despite command arrangements, not because of them. Throughout the1800s, the Army and Navy were co-equal. They "cooperated," but neither "commanded" the other. They were "partners," almost "allies" - and not necessarily friendly allies, either. Everything depended on personalities, as commanders who got along well personally worked together effectively. One of Ulysses S. Grant's many strengths was that he worked well with naval counterparts. He was the exception. Many senior generals and admirals spent almost as much energy quarreling with one another as fighting Confederates. Yet when the crisis of combat came, Army and Navy really did work together to gain victory, even if neither commanded the other.

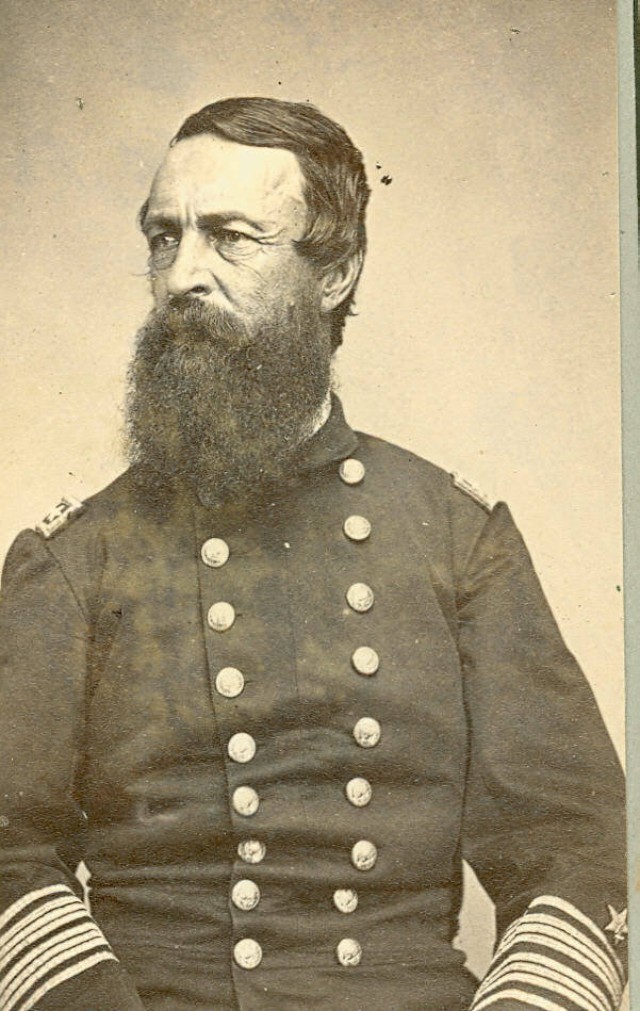

One such success came on January 15, 1865, where Cape Fear River enters the Atlantic, downstream from Wilmington, North Carolina. For most of the Civil War, Wilmington was the greatest Confederate port. From it vessels took cotton which earned gold to purchase military materiel that was imported through Wilmington. The Navy had blockaded Wilmington since 1861; by 1865, it was the main target of the most powerful Federal fleet, Rear Admiral David D. Porter's North Atlantic Blockading Squadron. Even then, however, an estimated 50 per cent of all blockade-running ships penetrated the cordon. To make the blockade effective, Fort Fisher -- the great earthen stronghold at the mouth of Cape Fear River -- must be captured. That mission required Army participation.

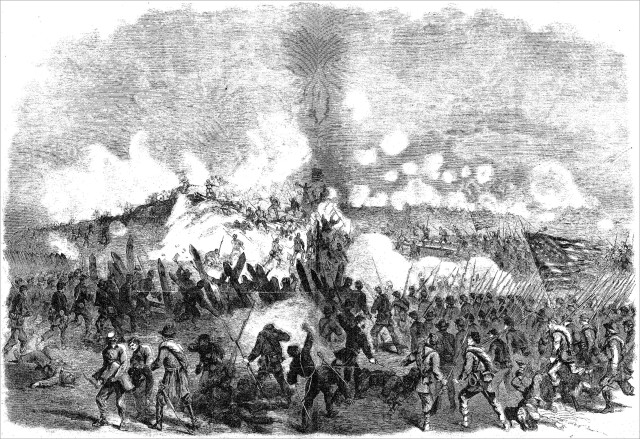

Under covering naval fire, Brigadier General Alfred H. Terry's six brigades landed on the peninsula north of the fort, January 13. A Black division and white brigade guarded the rear against attack from Wilmington. Three other white brigades under Brigadier General Adelbert Ames headed south toward Fort Fisher. Later that morning, the U.S. Navy began bombarding the fort's seaface. For three days, 59 warships threw 20,000 shells into the fort.

The Navy sent a landing party of 2,000 Sailors and Marines, armed with pistols and cutlasses, ashore, January 15, to "board" the fort, but the hard-fighting Graycoats repulsed the naval contingent. Although Porter had not fully coordinated this assault with Terry, it nevertheless focused the defenders' attention on their northeastern salient. That gave Ames opportunity to storm the fort's northwestern works. There and all along the line, Confederates resisted desperately. One Union brigadier was killed; two others were grievously wounded. The wounded Secessionist commander, Major General Chase Whiting, would die in Northern prison. Slowly, surely, from one traverse to the next, the Yankees fought their way along the ramparts. Black and White reinforcements from the unthreatened rear line bolstered them. Finally, after midnight, the last Southern citadel surrendered. Nearby forts were abandoned, January 16.

Wilmington was not the last Confederate port, not even the last Atlantic port, but it was the greatest port -- and now it was lost to the South. The city of Wilmington itself was not captured until February 22, but its value as a port ceased with Fort Fisher's fall.

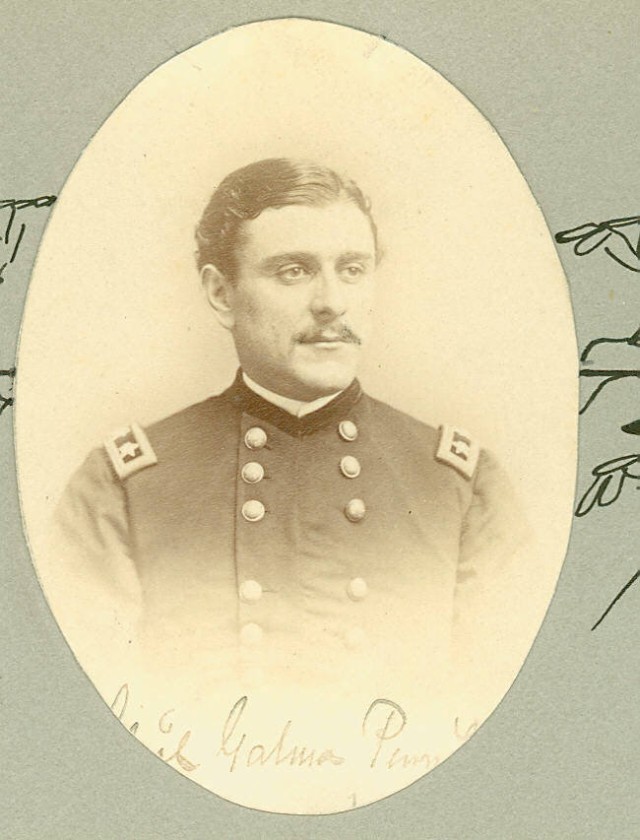

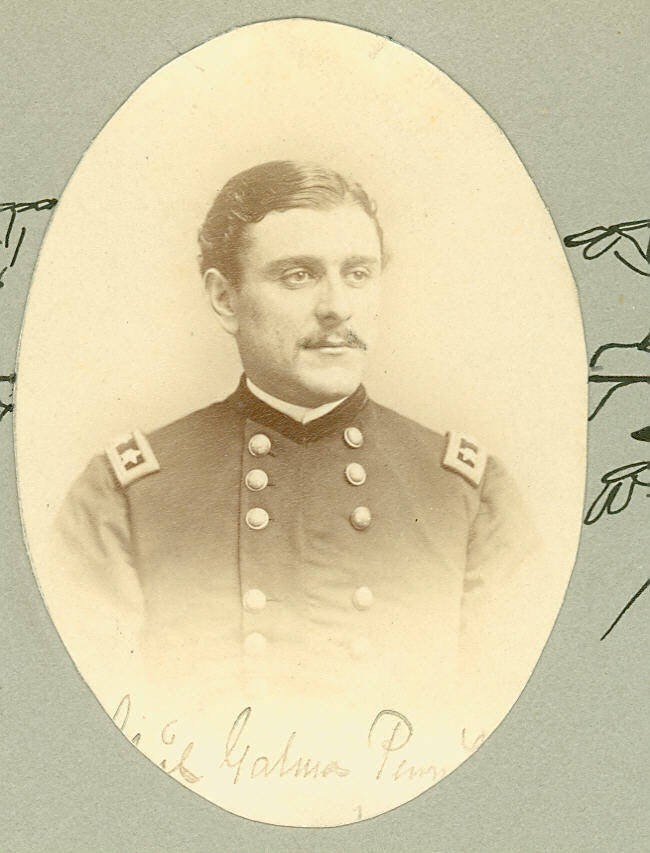

Terry -- a Connecticut lawyer -- was promoted Major General of Volunteers and Brigadier General of Regulars. Ames, who had graduated from West Point in 1861, would soon be brevetted Major General of Regulars. The two wounded brigade commanders were elevated to Brigadier General of Volunteers. One of them, Galusha Pennypacker, was only twenty years old -- too young to vote but old enough to lead Soldiers to victory. Eight Soldiers, 44 Sailors, and six Marines earned Medals of Honor.

No Unified Combatant Command, no Joint Command supervised this success. But citizen-soldier Terry and professional-sailor Porter did cooperate effectively. Together, the U.S. Army and the U.S. Navy gained a great victory, which contributed significantly to winning the Civil War.

Social Sharing