FORT JACKSON, S.C. (Aug. 27, 2015) -- Statistics on suicide in the military seem cold. Rational. Impersonal.

• Soldiers who have experienced recent demotions or family problems seem the most likely candidates for suicide -- especially women.

• About one-third of suicides among Soldiers are linked to mental problems present before the Soldiers enlisted.

• Soldiers report higher rates of hyperactivity and anger-management disorders than do civilians, both of which can lead to suicide.

But suicide itself is anything but cold and rational -- it's ugly and, even when you think you know what to do, it seems impossible to fight. The Army Medical Command calls suicide "the Army's unceasing enemy."

A Fort Jackson Soldier killed himself in a very public manner barely a month ago, leaving those behind wondering what more they could have done.

"The one thing I was most proud about was how involved the leaders were" in addressing the risks faced by the suicidal Soldier, said Col. Milton Beagle, commander of the 193rd Brigade and a former colleague of the Soldier.

"The leaders had done everything you could have expected them to do … down to the last day" the Soldier was alive, Beagle said.

"We take it for granted (that) we do know a lot about our people," but sometimes "it just kind of gets you" that what you know might not be enough.

September is National Suicide Prevention Month. The Army also will observe a month of educational and prevention activities under the mandate to "Take Action."

Laly Rodriguez, suicide prevention program manager for Fort Jackson's Army Substance Abuse Program, wants those on post to ask themselves this month: How does your unit take action? And, what will you do personally to take action?

"We need to be involved with Soldiers," she said. "What we have been doing isn't really working" and one month focusing on suicide isn't enough: "I want the entire year to make Soldiers resilient" enough to seek help, not death.

"I want to encourage commanders that they need to be somebody to trust. Most important -- they need to know their Soldiers."

She commended Beagle as someone who worked hard to know the Soldiers he commands.

"With me, it's always about seeing yourself" for who you really are, Beagle said of his methods -- Soldiers bear primary responsibility for knowing their strengths, as well as their faults and foibles.

"We put those on the table early and often" for discussions among Soldiers or the command team.

Beagle also expressed thanks that "somebody got me (a) gift a long time ago" -- an officer's guide from the 1950s.

That book, Beagle said, told him that "an officer should know those that they lead."

Through the years, he has experimented with memorizing names. Once he had mastered names, he worked on memorizing one personal detail per Soldier.

Chief of Staff Col. Morris Goins has sought help himself -- not because he was suicidal but because he found it difficult to cope with the loss of Soldiers during the height of fighting in Iraq.

"I needed help to process my experiences in Iraq after losing Soldiers," Goins said. "I was not suicidal, but I did need help with my emotions.

"It is OK to seek help," he said, but the process may not be easy. Those who need help should "be ready to lay it all on the line when you go for help, or you will be wasting your time and the time of those there to help you."

Last year, a non-commissioned officer at Fort Sill received accolades for preventing the death of a Soldier with whom he had once deployed. The Soldier had slit his wrists, then posted a picture of his injuries on Facebook alongside a one-word status: "Goodbye."

"I need my Army family to reach out and find where (name of Soldier) is at and get his unit to put their arms around him soon!" wrote Sgt. Maj. Jeffery Powell. "He may be in serious danger."

Less than five minutes later, colleagues found the Soldier at his overseas posting.

The Army has taken steps to combat suicide, from conducting behavioral studies to determine the causes of suicide, to increasing screening and prevention efforts, to developing a so-called anti-stigma campaign to get Soldiers to seek help for invisible emotional wounds.

"If you don't feel good" and tell that to a commander, Rodriguez said, "I don't see that as a weakness.

"We need to talk (about it) just like diabetes -- it's health."

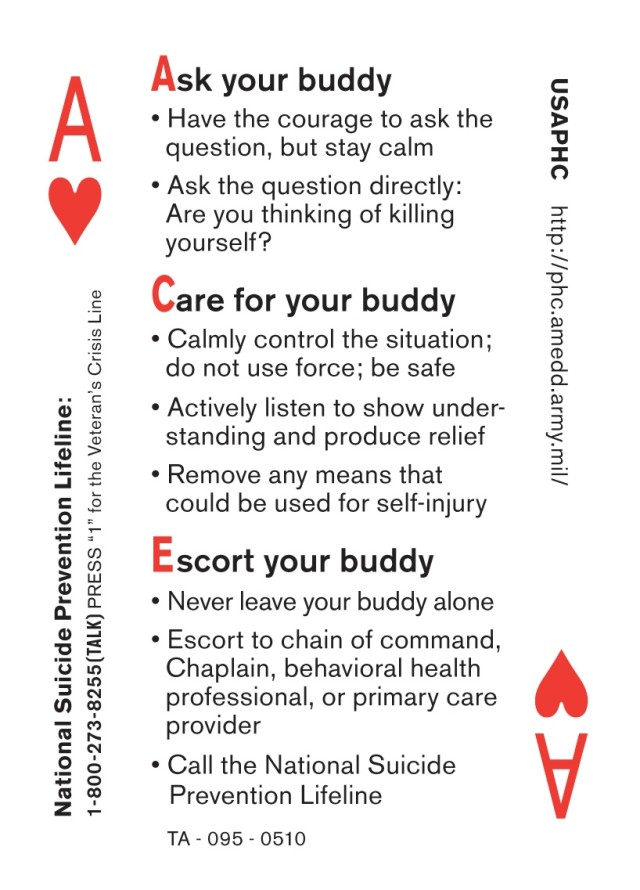

Chaplains, commanders, drill sergeants and counselors receive training in suicide- risk recognition and intervention. Soldiers and civilians receive cards that tell them to "Ask, Care and Escort" Soldiers in danger of suicide to the help they need.

"The loss of an American Soldier's life is a great tragedy, regardless of cause," says a 2008 "posture statement" from the Army Suicide Prevention Program. "In the case of suicide, the Army is committed to providing resources for awareness, intervention, prevention and follow-up necessary to help our Soldiers, civilians and their Families overcome difficult times."

Social Sharing