WATERVLIET ARSENAL, N.Y. (Aug. 19, 2015) -- If the old adage that "light gives life" is true, then the work that Army researchers are conducting at the U.S. Army's Benét Laboratories with private industry and academia should, if application follows research, provide a better life for mankind and for Soldiers.

The magic of light has an immeasurable effect on one's quality of life. The warmth from the spring light launches great growth outdoors, while giving us that extra motivation to get things done after a hard winter. The morning light introduces the work day and makes us feel better now that the unknown is revealed. And light not only heals, it also allows us to discover.

Given the power that light brings to our daily lives, imagine the possibilities if scientists could light up the darkest parts of our world. Well, maybe they can.

Benét Laboratories, which is located on the Army's Watervliet Arsenal in upstate New York, brought together this month about 20 of the nation's experts in a field of research, which involves a relatively new material called "black silicon."

One of the great things about black silicon is that unlike other natural resources such as gold and crude oil, there is an abundance of this material that can squeeze out the faintest light from the dark skies…or what the researchers call "moonless clear starlight" nights.

Jeff Warrender, who has a Ph.D. in applied physics and is Benét's leading black silicon researcher, has been hosting these scientific gatherings since 2009.

"The goal to these gatherings hasn't changed much since we started hosting these workshops several years ago," Warrender said. "We simply want to build a community of awareness in the field of black silicon that will accelerate the research so that we may develop applications that will make our Soldiers safer and more effective on the battlefield."

The topics of this workshop were not for those who did not have solid roots in scientific research and development. From Harvard University's Ben Franta, who presented "Nanosecond laser annealing of black silicon," to SiOnyx's Dr. Martin Pralle, who discussed "current performance and application for imagers," each presentation helped bring light, if you will, to the current state of black silicon research.

How is it that Benét Labs can motivate the nation's best black silicon researchers to gather at Watervliet?

Pralle, whose Massachusetts company is a spinoff from Harvard University, said Benét Labs, through Warrender, has taken the initiative and the lead in the Department of Defense to provide the necessary platform for future black silicon innovation.

"Jeff (Warrender) has the intellectual background to understand the technological roadmap that we are developing in this field," Pralle said. "Additionally, Benét Labs is well connected to key DOD organizations and to other military research centers that can directly benefit from black silicon innovation."

Research and innovation is good, but at some point there must be some application to this new technology to gain a return on investment by providing enhancements to the public's and Soldiers' lives. Or what Pralle describes as "bridging the gap between science and application."

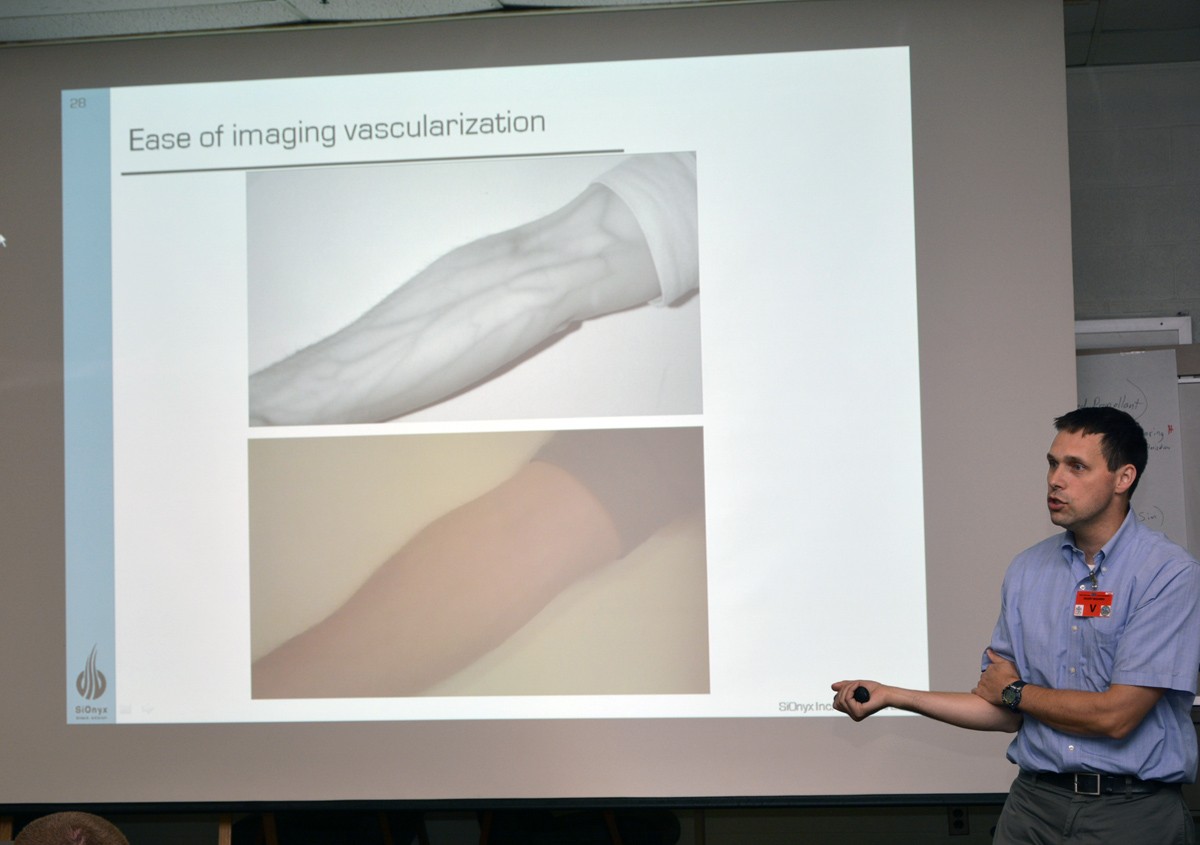

"We have actually done quite a bit with black silicon," Pralle said. "For example, our sensors offer unrestricted imaging from day to moonless night."

Security surveillance is, by and large, the most important near-term application of black silicon, Pralle said. Traditional nighttime security cameras use infrared LEDs to light up the night so that cameras can see. This draws excessive power and provides visibility only within the illuminated region of the scene. The SiOnyx cameras operate with native illumination such that there is a significant power savings and the whole scene or image can be seen without flashlight effect encumbrances.

To state that there was a high state of interest and enthusiasm in this group of researchers from DOD, private industry, and academia would be an understatement.

"This research is really, really cool and our ability to attract such a diverse, technically engaged audience to this event says a lot about the quality and importance of the work being conducted at Benét Labs," Warrender said. "It all comes back to the Soldier - in this case, improving the Soldier's battlespace awareness and mission effectiveness. Our ability to develop a broad network of expertise around this material gives me optimism that black silicon can deliver an important capability enhancement to the Soldier. That's always our highest priority at Benét and I think this work reflects that commitment."

BLACK SILICON

Just as visible light comes in many different colors, infrared light also has a broad spectrum of colors, but most pass right through ordinary silicon imagers without being absorbed. The black silicon community's goal is to devise techniques to modify silicon's properties so that it can absorb more of these infrared colors while still taking advantage of the manufacturing infrastructure that produces inexpensive silicon-based imagers and devices such as camera phones.

Black silicon was discovered at Harvard University in the late 1990s by accident when Professor Eric Mazur decided to use sulfur hexafluoride, a gas used in the semiconductor field, to do something different in a last-minute effort to retain Army research funding.

Armed with the sulfur gas, they hit a silicon wafer with a laser and the wafer turned black. What Mazur discovered was that the wafer had a dramatic absorption of infrared light over the typical silicon wafer.

_______________________

Benét Laboratories is a Department of the Army research, development and engineering facility located at the Watervliet Arsenal. It is a part of the Weapons & Software Engineering Center (WSEC), an organization under the Army's Armament Research, Development, and Engineering Center (ARDEC), which is located at Picatinny Arsenal, N.J.

The Watervliet Arsenal is an Army-owned-and-operated manufacturing facility and is the oldest, continuously operating arsenal in the United States, having begun operations during the War of 1812. It celebrated its 200th anniversary in July 2013.

Today's Arsenal is relied upon by U.S. and foreign militaries to produce the most advanced, high-tech, high-powered weaponry for cannon, howitzer, and mortar systems. This National Historic Registered Landmark has an annual economic benefit to the local community in excess of $90 million, and its 2014 revenue was about $117 million.

Related Links:

Arsenal Story: Watervliet Arsenal, Public-Private Partnership's Capabilities Deemed to be Ship-shape

Army.mil: Science and Technology News

Watervliet Arsenal Slideshare Page

Watervliet Arsenal YouTube Page

Watervliet Arsenal Twitter Page

Social Sharing