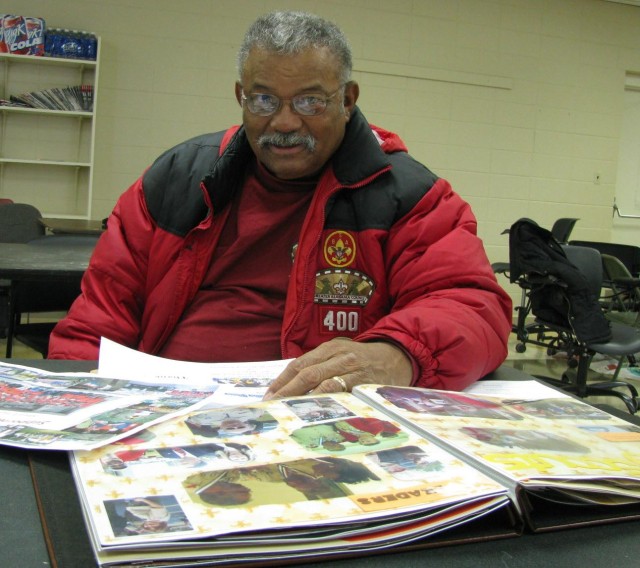

Retired 1st Sgt. Albert "Al" Farrar wasn't at the Veterans Day Dinner when his name was called out as the recipient of a lifetime achievement award presented by the North Alabama Veterans and Fraternal Organizations Coalition.

It wasn't that he didn't want to be present to receive such a prestigious award. If he had known about the award, which he didn't, he would have rearranged his schedule to make sure he was there.

But, without realizing the momentous occasion he was missing, Farrar went about taking care of a previous engagement he had scheduled with a few young men. While other veterans and community leaders were dining at the Von Braun Center's North Hall, Farrar was going over the details of a flag retirement ceremony that members of Boy Scout Troop 400 would be involved in on Veterans Day.

"What I enjoy doing is changing the character in boys. I'm not doing this to get recognition," said Farrar, who has been the Scoutmaster for Troop 400 since it was started in 1988.

"Plaques collect dust. My satisfaction is to see a boy grow into a responsible and productive young man. I want to do this for the rest of my life."

Farrar, 73, received the lifetime achievement award for his nearly 30 years of work as a Boy Scout leader. He is a retired Soldier who stumbled into Scouting thanks to his own son's desire to be a Boy Scout.

"I took my son fishing and he didn't like that. I paid for golf lessons and tennis lessons for my son, and he didn't like doing those either," Farrar said.

"And then he got into a Scout troop. He really loved Scouting. So, I switched all my habits over to what he enjoyed."

Farrar's son, Albert Jr., was a member of Boy Scout Troop 102, and Farrar was its Scoutmaster. After his son graduated from high school and went on to West Point, Farrar left Scouting. But it wasn't long before he was asked to be a unit commissioner for Boy Scouts.

"Troop 400 was a unit that just happened to be in my area. But at that time it was just a troop on paper," he said. "So, I volunteered to be its Scoutmaster. It gave me an opportunity to make a difference in some kids' lives who really, really needed it."

Boy Scout Troop 400 is an interesting mix of about 85 boys from throughout Huntsville. Most of the boys come from the city's public housing projects, such as Council Court, Butler Terrace, Northwood, Lincoln and Lakeside. Every Saturday, they come together at the Albert F. Farrar Sr. Boy Scout Hut on Dallas Avenue in downtown Huntsville.

"The number of boys we have is a 'moving number.' Our boys come from transient neighborhoods," Farrar said. "People come into public housing and then they get out. Boys come into our program when they live here. We can't kick them out when they move on. Most of them have their roots in public housing."

The troop provides many activities for its members. Besides working on merit badges and advancing in rank, the boys go on camping trips and snow skiing, and they participate in several community events, including Flag Day ceremonies at Veterans Memorial Park. The troop operates on a $75,000 a year budget, and has two 15-passenger vans and a 19-passenger bus that pick up boys from various public housing neighborhoods to transport to meetings and events.

"We're blessed. We get an annual grant from the Housing Authority because we provide youth development activities. The rest of our money comes from parking concessions during events at the Von Braun Center and during Panoply and Big Spring Jam," he said.

"The one thing about being a Scout troop is everybody wants to help you, especially in low income neighborhoods. People are very generous."

Though their official meetings are on Saturdays, Farrar sees many of his Scouts throughout the week. The Boy Scout Hut is open Monday through Friday from 3-7 p.m. for Scouts and any other neighborhood children who need a safe haven or a place to get homework help.

"We want our boys to live by the Boy Scout oath and law," Farrar said. "We want them to take advantage of educational opportunities. We want them to realize their future depends on how well they do in school. We work hard to get them to see the value of a good education."

Scouts participate in monthly essay writing contests on issues affecting their education, behavior and expectations. They share leadership positions in the troop, often vying every six months to serve in a position. Farrar has six retired veterans who help with the troop.

"They are goal oriented and compassionate about what they do. They are making a difference in these boys' lives," he said.

However, it can be difficult at times to see the difference they are making.

"We are dealing with boys who have a value system that is turned upside down," Farrar said. "They think 'If I don't get caught, then it's OK.' They will get the paperwork and do all the requirements for Eagle Scout (the highest ranking) and then they will go out and steal a car. They meet all the requirements for Eagle Scout except the ethical part. They don't have the right values."

In the 20 years he's been volunteering with Troop 400, there have only been two boys who have made Eagle Scout. The boys' value systems along with the lack of parental support and good parental role models are roadblocks in achieving the highly respected Eagle rank.

There was a time when that bothered Farrar. But he has come to realize that it is up to the boys, not their Scout leaders, to make the right choices for a better life.

"I had a preacher tell me once 'I deliver the message and the Lord converts the heart.' The best job you can do is present the program to the boys and hope they will respond," Farrar said. "As leaders, we can't think we failed because the kid failed. We stress values hard, but the boys have to decide to accept those values and live by those values. And you can't make Eagle Scout if you can't live by the Boy Scout law."

Farrar's goal is not necessarily to have more Eagle Scouts come out of Troop 400. His goal is to help the troop's members grow into productive young men with values.

"We really stress that they need to look down the road and look around and see where they are headed," he said. "As a Scoutmaster, I'm about the only man in most of their lives. I talk positive to them about the possibilities they have.

"I try to point them toward not making the same mistakes of their mother or father. I tell them their opportunities are better. I tell them 'Don't let the situation you are in now affect your future. Don't let where you are drag you down. You've got in your hands the opportunity to make yourself better.'"

Farrar had a much different childhood than the boys of Troop 400. He grew up in a household where there were two parents who stressed education and opportunity. They gave their son boundaries and taught him values.

But, like the boys he works with today, Farrar also had to decide for himself what his future would be. Farrar joined the Army in 1954, after realizing his parent's dream for him to become a dentist just wasn't what he wanted to do.

"A big influence on me was that I grew up during World War II," he said. "My hometown in Virginia was on the route of a lot of military trucks. I'd see those trucks and think 'One day I'm going to be on that truck.' My parents had a different idea. After a year at Virginia State College, I made up my mind to do it my own way. I had no idea of staying there. My mind was made up."

Farrar was assigned to the Army's nuclear weapons program. His focus was on Redstone and Pershing missiles, with assignments in Germany and at Fort Sill, Okla., and Redstone Arsenal. His last assignment during his 23-year military career was as an instructor at the Arsenal, where he received instructor of the month several times.

"The whole Army career prepared me for this type of thing," Farrar said, referring to Scouting. "As an instructor, I taught boys every day, not only about missiles but also about life skills. The Army gave me an opportunity to learn and to teach and to lead men."

After retiring as a first sergeant, Farrar spent another 17 years working as a DoD civilian on Redstone Arsenal, where he worked in computer maintenance and test equipment. Besides Scouting and various community activities, Farrar spends his retirement days with his wife, Verline. They have two daughters, Verlinda and Cordai, who live in Atlanta, and their son Albert Jr. is a major in the Army.

This year, as part of a Veterans Day program at Huntsville Middle School, Farrar revisited his old Army days. He was asked by many of the boys in his troop who attend Huntsville Middle to wear his uniform for the program.

"I hadn't been in an Army uniform in 30 years," he said. "I pulled my uniform out of a closet and took it to the tailor. I asked if he could make it fit and he just laughed at me. But he put in a panel in the back and I could get the jacket on.

"I wore it to the program. The boys were real proud of me. They followed me around the school like I was Santa Claus."

Social Sharing