BAGRAM AIRFIELD, Afghanistan, April 19, 2015--In this race, it's said that the big guys will run slower and the little guys will run faster. But this isn't your typical competition. This marathon is happening inside a small room at Bagram Airfield and it's the bad guys -- the DNA type -- that won't cross the finish line.

Jennifer Hammons is the lead DNA examiner at BAF's Afghanistan Captured Material Exploitation (ACME) laboratory, the only forensic operating lab in theater. And it's the genetic analyzer that helps her catch the enemy. And all she needs is a drop.

"The thing I love the most in situations like this is when we have something that looks like nothing and we wind up with a great answer," she said, explaining her machines and the multi-step DNA process. "Parwan has the highest conviction rate in Afghanistan. And we're able to get individuals detained or off the streets."

Hammons said the DNA process is divided into four steps. And it's the extraction process that separates the DNA from the rest of the cells.

Next, she turns to the thermal cycler, a machine used to amplify segments of DNA.

"This is where the magic happens," she said. "This is where amplification occurs. What it does is it mimics what happens naturally in the cell -- when our cells divide and replicate DNA. If you get a cut on your finger, your cells are regenerating to heal that area back up. Well, that's kind of the same scenario. All of the magic is happening here."

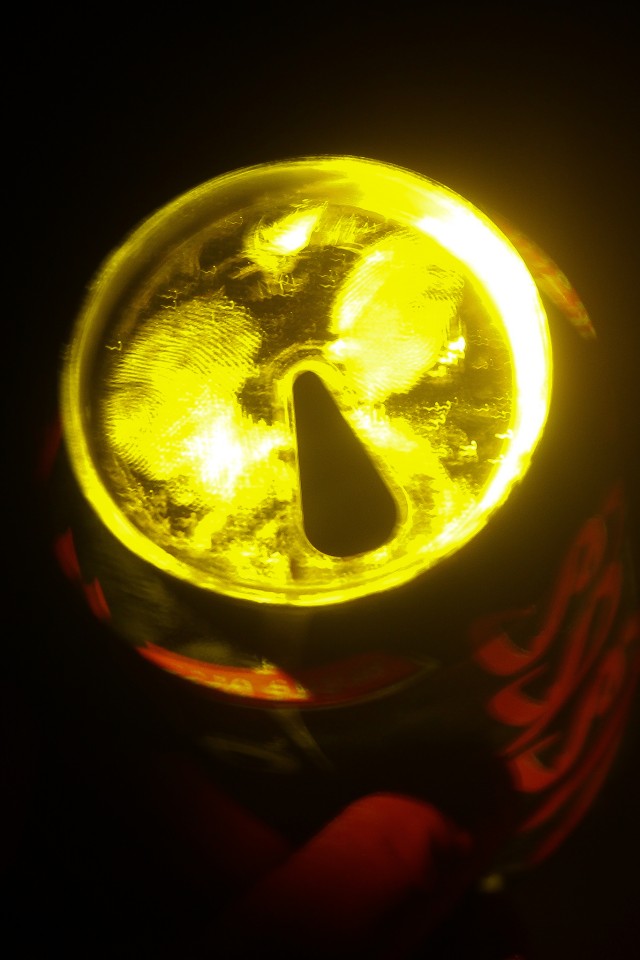

A billion copies of DNA are made in ACME's post amplification room. And the billion copies are now detected by a genetic analyzer.

"So there's a plate in here and it has a tiny, tiny, tiny amount of sample and I mean a drop," Hammons said, standing in front of a genetic analyzer. "And what happens is this plate moves. And these 16 probes here will inject into 16 samples. And then what it does is applies a charge or current. And what happens is, since DNA is negatively charged, it is attracted into that platinum. And what it does is it migrates up the capillary which is hollow and it runs, runs, runs. It's kind of like a race. Big guys are going to run slower and the little guys are going to run faster."

Next, DNA fragments are separated by size, tagged with colors and, eventually, separated by size and color. Pictures are taken and the machine takes that information and applies an algorithm. And that's how a DNA profile is generated.

Hammons can run about 70 samples at a time. On average, she runs about 50 samples per week.

"So there's not one instrument that identifies the bad guy," she said, "but rather a combined effort from the four steps that lead to a final product. For me, that's a DNA profile."

At BAF for five months, this is Hammons' third deployment to Afghanistan. In 2011 and 2012, she was at Camp Leatherneck, an Afghan Armed Forces base in Helmand Province, Afghanistan; and then Bagram in 2013. She comes from the Defense Forensic Science Center (DFSC) in Forest Park, Ga. -- where most of the ACME workers are from. The U.S. Army Criminal Investigation Laboratory (USACIL) is located within the DFSC at the Gillem Enclave in Forest Park, Ga. USACIL is the only full service forensic laboratory in the DoD.

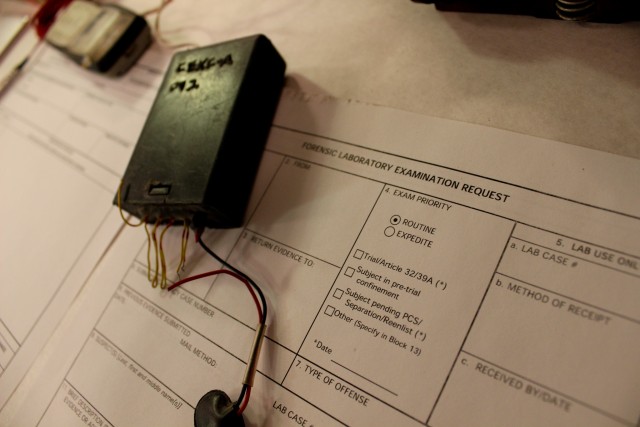

In 2006, the Department of Defense established Joint Task Force Observe, Detect, Identify, Neutralize (JTF ODIN) as an Aerial Intelligence Surveillance Reconnaissance (A-ISR) Task Force to defeat improvised explosive device networks. During transition to Resolute Support, the Task Force transformed into the U.S. Forces -- Afghanistan joint multi-disciplined intelligence brigade responsible for synchronizing ground and aerial intelligence operations across the Combined Joint Operations Area-Afghanistan. The ACME lab is a subordinate task force providing critical forensic analysis including DNA, finger print, and weapons technical inspections to identify force protection threats and enable host nation criminal prosecutions.

Crystal Allen, ACME lab manager, oversees all of the forensic disciplines at ACME. She also works out of the DFSC that also has lab assets in Bahrain, Djibouti, and Kuwait. This is her third deployment. And she's the first female ACME lab manager.

"It makes me feel proud and thankful," she said. "I work with an incredible, supportive team and this has been one of the most rewarding opportunities I have ever been given."

So each of the people you've met today -- their job is to deploy," she said. "We stay stateside for a year and then we rotate forward to one of our locations for six months. I think it's just incredible that we can apply forensic science to the needs of the battlefield. It does not get old. It's certainly high impact not just for us personally but for the teams in the field as well."

The lab trains from 30 to 60 Afghan judges, prosecutors, and law enforcement professionals from around Afghanistan every six weeks at the Afghan National Security Justice Center in Parwan Province. The center is an Afghan multi-security complex that includes judges, prosecutors, defense counsel, and investigators that have enabled the government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan to become a credible counter-terrorism partner that can effectively detain, investigate, and prosecute national security threats.

"They're trained in how to collect DNA, latent prints, and perform evidence collection," Allen said. "That way when they go to the court room, they can explain the results properly. We support the promotion of the Rule of Law in Afghanistan by helping the Afghan government develop a better understanding of forensics to aid in prosecution and sentencing of offenders. Based on the results we obtain from evidence, we assist the Rule of Law team here on base with prosecution support packages that are used in the Afghan courtrooms."

Larry Brown, liaison officer for the Law Enforcement Professional (LEP) Program, has been working here for two years. His job is to provide training, advice, and assistance to LEPs throughout theater. Brown also provides training, and mentors Afghan law enforcement.

"Our responsibilities are to aid, assist, and mentor the U.S. and coalition forces, as well as Afghan law enforcement," he said. "LEPs mentor the Afghans on proper procedures in collecting, packaging, and submitting evidence from IED events plus the Rule of Law so they can present their cases in court resulting in successful prosecutions."

Brown said that, in August 2014, as a direct result of ACME forensic analysis, the LEP Program was instrumental in publishing a "BOLO" or be-on-the look-out book of Afghans who are biometrically linked to IED events in Afghanistan. These BOLO books are printed in Dari and provided to Afghan law enforcement to enable them to identify subjects at check points, border crossings, and in villages. When published, it listed about 1,600 names and photographs. Today, it lists almost 1,800.

"A little over 200 of those people have been prosecuted and sentenced," Brown said. "So it's a great law enforcement tool for the Afghans."

Lonnie Jones, at BAF since September 2014, is a forensic chemist at USACIL and has over 20 years of experience in the field, primarily with drug analysis. And when he found out ACME needed someone to investigate explosives, he answered the call.

He said from last fall through this February, he was averaging about 17 cases per month -- primarily explosives analysis.

"Mostly what we end up getting is a post-blast, something that's already gone off," he said. "What remains of the evidence is submitted to us. We get a lot of fragments and other materials that were a part of the original explosive itself. And from that I do extractions and identify the different components."

He says the equipment at ACME is unique to the region.

"I don't think there's any place else in Afghanistan that has this variety of equipment," he said. "We're pretty capable of doing just about any explosives analysis. We also do some drug analysis. Our capability is pretty vast."

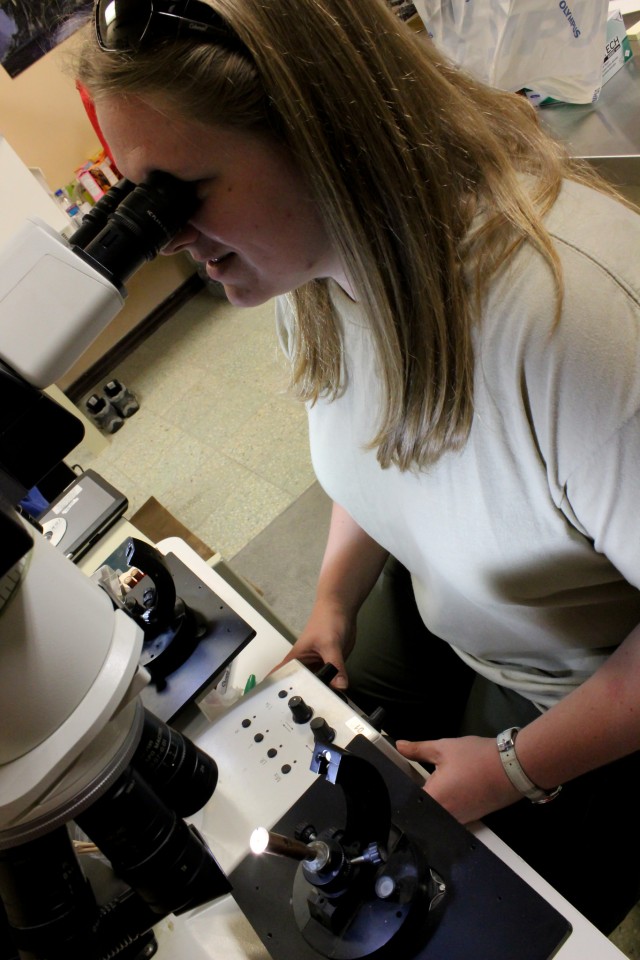

Different types of evidence, often with fragile prints, are examined in the processing room, where Delilah Ortiz-Bacon, lead latent print examiner, works. This is her third rotation out to theater in four years. She's been here at BAF since February 2015 and comes from the DFSC's Forensic Exploitation Directorate, where she's worked for five years.

When evidence is received, the first thing Ortiz-Bacon does is look at it under a strong light source. She said as objects are broken down, each component is examined so that the different types of surfaces are processed with the most appropriate method. For example, on nonporous surfaces like plastics and metals, fingerprint residue will sit on the surface. And that equals a fragile print because it can be wiped off during handling or collection.

She is also an International Association for Identification -certified latent print examiner. There are only about 900 people certified in the world -- and more than 20 of them work at the DFSC.

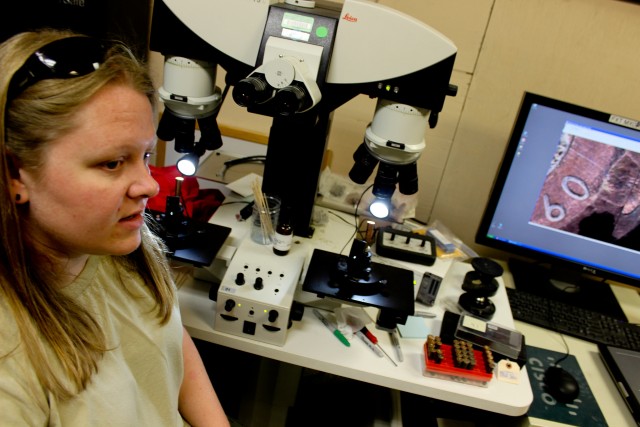

Teri Shaffer, firearm and tool-mark examiner, comes from the DFSC. And she said that, essentially yes, every gun has a fingerprint. The manufacturing process leaves individual marks behind on the parts that come into contact with the cartridge case and the bullet. So she can look at those marks that were left behind and identify them to a specific firearm.

She also said that even though her job is to examine firearms, a lot of times there are none. Meaning she receives bullets and cartridge cases only. Her reports include things like make, model, caliber, country of origin, and serial number. She also test fires for microscopic comparison.

Maj. Ty Dawson, officer in charge, arrived this February for a nine-month tour. He comes to BAF from the 71st Explosive Ordnance Disposal group in Fort Carson, Colo., with a background in explosive ordnance disposal. His job is to provide military oversight.

He said that as the mission has sloped off with a lot of outside-the-wire-type engagements, the lab has fallen more into a force protection role with actions being impactful in the Bagram ground defense area. Also, he said it's important for them to be able to provide prosecution support to the Afghans.

"And that's really where our link to train, advise, and assist comes in," he said.

And he said although he came here with a tactical forensics collection background, he's already learned a lot from this group.

"I'm getting educated on a much deeper level and a much higher level about what this is. ACME is a technical, forensics and biometrics-intelligence-producing enterprise," Dawson said. "It is a closed system that produces information into the open system in the intelligence community. In that regard, my functional understanding of where the lab sits in the grand scheme of things has increased greatly. I'm the only uniform service member that's actually attached to the lab. It's the technicians and scientists on the team who are truly the stars."

Social Sharing