WASHINGTON (Jan. 16, 2015) -- Active, Guard and Reserve Soldiers assigned to warrior transition units, which may be hundreds of miles from where they live, now have access to community-based, outpatient care and services in their hometowns.

The Army recently stood up 11 community care units, or CCUs, spread across the country and will add another one in the coming months, said Brig. Gen. David Bishop, commander of Warrior Transition Command and the Army's assistant surgeon general for warrior care and transition. CCUs fall under his command.

CCUs provide command and medical management assistance to Soldiers as they navigate the Army's medical treatment system to successfully reintegrate back into the force or transition from the Army, Sgt. 1st Class Michael Miller said.

Miller, the CCU platoon sergeant at Fort Carson, Colorado, explained that while Soldiers can remain at home throughout their recovery process, there may be an occasion when a visit to the installation will be beneficial to them, so about once a quarter, they attend a week-long Soldier readiness review, or SRR.

For instance, this week, six Soldiers in the CCU who live in remote areas of Colorado, Utah and Nevada, attended a number of SRR events at the installation that, he said, will better prepare them to recover from their wounds, injuries or illness and then either remain in the Army or transition to civilian life. It was the first of its kind at Fort Carson, since the CCU there was stood up in September.

TEAM BUILDING

The Soldiers took part in a number of team-building exercises, including sitting volleyball and wheelchair basketball.

Although none of the six are amputees, the adaptive reconditioning activities helped them to better realize that people with very severe disabilities can still function at a variety of motor-skill tasks after rehabilitation, Miller said.

"It was a bit intimidating at first, but was actually a lot of fun. We can now see how [amputees] can participate in sports they love," said Staff Sgt. Lynda Santiago, a CCU member from the Colorado Army National Guard, who lives in Evans, about a hundred miles north of Fort Carson.

She added that the exercises helped bond the six and also helped them build confidence.

Throughout the team-building exercises, Miller said he saw the Soldiers developing "trust, cohesion and empathizing with each other."

Although Miller himself was never wounded or injured during a tour in Iraq, the infantryman said he has friends who were and that he realizes it could have easily been him. He added that he's glad to have the opportunity to help his fellow Soldiers through their recovery process, having seen first-hand some of the traumatic events Soldiers encounter.

PERSONAL CONNECTIONS

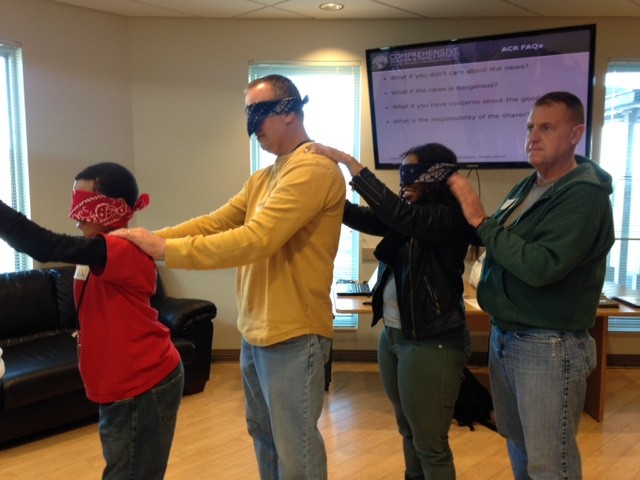

Kelly O'Brien, a master resilience trainer-performance expert with the Comprehensive Soldier and Family Fitness Training Center at Fort Carson, taught the Soldiers resilience skills designed to build connections and improve communications with others. An Army chaplain at the Fort Carson Warrior Transition Battalion also participated in the workshop.

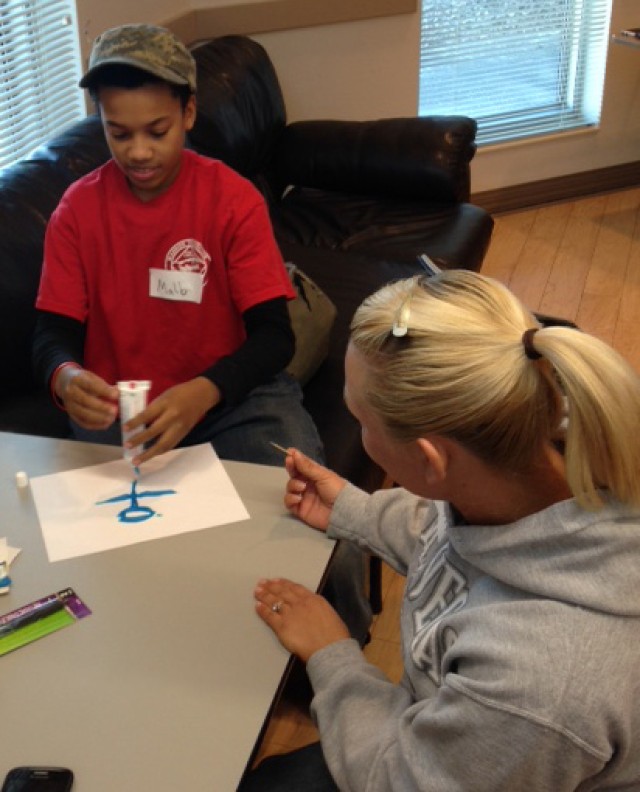

The group began with an activity designed to build better personal connections with others.

Small groups used toothpaste to draw an abstract illustration that had some sort of meaning to them, O'Brien said, explaining that it wasn't really important what they drew. Once they finished, they were asked to scrape up all the toothpaste and put it back in the tube.

They succeeded in putting most of it back, she said, but there were traces of toothpaste left behind on the paper that remained.

The moral, she said, is that "the words that come out of our mouths are so critical and so important to interpersonal connections. The words can absolutely enhance [that communication] or they can be very detrimental. Words, like toothpaste, come out easily, but the words, like the toothpaste, are very hard to take back. Even if you succeed, it's going to leave a mark."

One skill O'Brien taught was active constructive responding, or ACR. ACR addresses how a person responds when someone brings them good news. How a person responds to another profoundly affects their relationship, she explained.

Participants were asked to write down key people in their lives, such as family members or other Soldiers and so on. The participants were then instructed to write down how they'd respond to certain remarks by those key people. For example, she said one woman shared how she often responds to her mother in ways detrimental to positive communications.

Ways to better respond correctly were discussed, O'Brien said, adding that people might not always be aware of negative responses they give, even when good news is received.

An example of what she termed a "conversation hijacker" might be if a loved one suggests a vacation to Hawaii and the other person responds with something that's totally unrelated.

Or, the response might be "that's too expensive," or "it takes so long to get there." She termed these "joy thief" responses.

Another example might be not actively listening to key people, she said. When that key person perceives his or her message going through one ear and out the other, the person feels that message and perhaps that relationship is not very important and disengagement occurs.

The ACR optimal response would be to show genuine interest in listening and following up with positive responses and questions, she said. This allows the key person to relive the experience and linger in the positive emotion.

"Hunt the good stuff" was another skill, she said. This involved taking the opportunity to reflect on and look for all the good stuff that's happening in one's life. This activity needs to be done on a daily basis and practiced for it to kick in as an automatic habit.

"We know the bad stuff is going to find us," O'Brien said, "and being able to look for what's good, no matter how big or small it is, helps build optimistic thinking." She termed this looking for the "silver lining" in a situation.

It could be as small as someone bringing you a coffee, she said, or, the sun finally came out after a week of miserable weather. Or, you hit every green light coming in. "Really, any positive experience, and, you sometimes really have to hunt for them on bad days," O'Brien added.

Once hunting the good becomes habitual, a lot of positive things happen to the person, physically, mentally and emotionally -- better sleep, greater life satisfaction, increased optimism, and better relationships.

"Our grandparents told us to 'count our blessings,'" she said. "Now, science has caught up with grandma."

A FAMILY AFFAIR

The six Soldiers participating in the CCU event at Fort Carson were given the opportunity to bring their families with them to the various activities, employment workshops, as well as their medical appointments.

Santiago brought her husband and mother to Fort Carson and said the experience gave them a better understanding of the support wounded warriors need.

For example, she said they learned how many with post-traumatic stress disorder can become mentally and physically detached from others and their environment. The detachment results from Soldiers feeling that others don't understand what they're going through and they withdraw.

Family members, friends and other Soldiers are encouraged to try and get people with PTSD out of their rooms and incorporate them into activities and reassure them that they are valued and appreciated, Santiago said.

As for Santiago's future, she plans to finish a college certificate program in industrial oil and gas processes and start a small company with her husband relating to environmental compliance.

The employment portion of CCU's transition assistance was very helpful for her future plans, she said, adding that it helped others as well, some of whom were offered civilian employment internships while they were still in the Army going through the recovery process.

"I'm really thankful they have programs like this," Santiago said. "I know that they didn't have these kinds of things in the past. Soldiers come into the Army 17 or 18 years old and don't have a clue about what civilian life will be like. This gives them the skills and training they need to know what to do. I'm just thankful for the program."

(For more ARNEWS stories, visit www.army.mil/ARNEWS, or Facebook at www.facebook.com/ArmyNewsService, or Twitter @ArmyNewsService)

Social Sharing