FORT DRUM, N.Y -- Turning on a faucet for instant access to running water is an everyday convenience in the United States. Nearly 200 years ago -- when James LeRay de Chaumont built his estate on what is now Fort Drum's South Post -- it was a luxury amenity.

Duane Quates, an archeologist with Fort Drum's Directorate of Public Works Cultural Resources Program, and other Cultural Resources staff members have been working to preserve and document the items found on the property surrounding LeRay Mansion.

A native of Brewton, Ala., Quates earned a bachelor's degree from the University of West Florida and a master's degree and doctorate in anthropology from Michigan State University. He became interested in anthropology and history during his service and travel in the U.S. Navy.

Quates had been observing a construction project to fix some of the drainage issues on the historic site when workers recently unearthed several wooden water pipes. The pipes, which were about 10 to 12 feet long, were connected by wooden or copper plugs that fit inside the opening, according to Quates.

Making the wooden pipes in the early 1800s was a long and tedious process, Quates said.

"They burned out the center (of the log) and scooped out the center with a spoon auger," he explained. "They would sit there and turn it around in the burnt-out center of the log … alternating burning and auguring until they got all the way through. It was a (time-consuming) process."

Workers have been finding wooden pipes on the LeRay property periodically throughout the last 10 to 20 years, according to Quates.

Some of the wooden pipes found on the property were original to the mansion, like the ones found in September. However, the ones found in October were installed later and were connected with copper fittings, Quates explained.

"There are round and square ones; the square ones were most likely produced in a mill in the later 19th century," he said. "The early ones are round and are basically hollowed-out logs -- some of them still have bark on them."

The location of the pipes helps Cultural Resources staff understand the layout and drainage of the water system, and how the landscape was planned. In addition, it provides clues to how the LeRays planned the construction of infrastructure they put in place back in the 19th century, Quates explained.

"We think that originally, there was a pump house near the stream that's … approximately 100 yards southeast of the mansion," he said. "We think that fed water into the basement. The house would've had a very rudimentary form of running water. It probably flowed into a basin or cistern."

The high water table around the property could be due to the old water system, which is why workers have been installing new water pipes recently. The high water table is most likely the reason why the untreated wooden pipes have stayed preserved over the years, Quates said.

"As long as it's submerged in water -- and we have a high water table here -- they preserve fairly well because they're in an anaerobic environment," he said. "The minute we pull them out of the ground, they'll start to decay slowly and start dry rotting."

The Cultural Resources staff decided to store some of the wooden pipes in the nearby LeRay Pond to try to preserve them, below a layer of silt and away from oxygenated water. Others have been stored in an old foundation west of the mansion. Although the ones that have been left outside in the elements have begun to decay over the years, they are still in pretty good shape, Quates noted.

While wooden water pipes were considered a luxury, they have been used for hundreds of years, he said. Wooden water pipes date back to 13th century London and were used a lot during the 18th and 19th centuries in the U.S.

Solving mysteries

Water pipes are not the only things Cultural Resources staff members have found around the property. The organization has a collection of hand-blown glass wine bottles near where the wine cellar used to be, as well as buttons, belt buckles, nails, ceramics and china, a barn and building foundations.

"We've found so much on the property," Quates said. "This place is a historic district and is located on the National Register of Historic Places.

"Back when I first started here, because my background is in historic archeology, I became immediately interested in the LeRay district … and I wanted to try to find the original house," he continued.

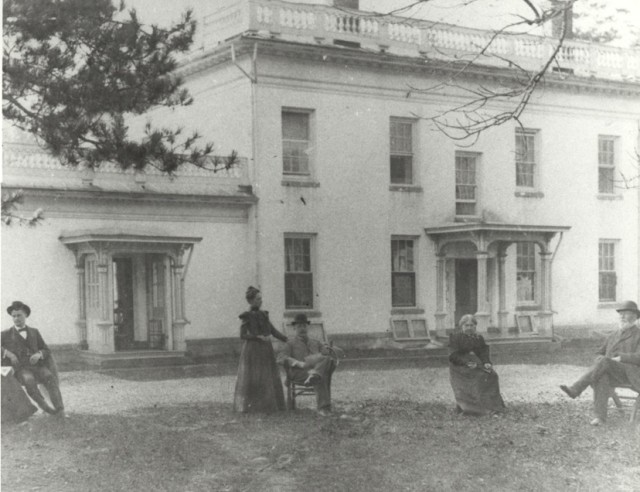

The original LeRay Mansion, which was built in the early 1800s, burned down in 1822. Researchers are still unsure of where the original home was located; however, Quates and other staff members located an area in the wooded area on the property that could possibly be the location of the original mansion.

LeRay owned roughly 2,000 acres of land, 200 of which were designated for his personal use, Quates added. The property changed hands a few times before the Army acquired the land in 1941.

"I've been conducting some digs just north of here on the edge of the lawn, looking for the original house," he said. "We don't know if it was on the same location. We excavated all around here."

In 2009, workers dug along the side of the foundation to reinforce the basement wall.

"(During that time), we were able to monitor that and screen the dirt," Quates said. "There was no evidence of burning at the location."

Quates and his team located early 19th century artifacts in a site a short walk north of the home. In addition to the items, the team found six to eight inches of white ash, indicating that an extremely hot fire had taken place on that site.

"The unfortunate thing is we haven't found any foundation walls to indicate what it is," he said. "We have interesting techniques to determine clues as to what was there. In that area, the most telling part are the nails we found."

The team uses an imaging technique called LIDAR, which uses light radar, to scan the topography of the ground. During the review of the land, Quates noticed a depression in the wooded area. While it could have been a dumping area or a building that decayed and collapsed, he saw that it resembled a cellar.

"We knew we had an ash layer, but we can tell whether it was a dumping area by the nails," Quates explained. "If we have a majority of nails that are crimped -- bent at a 90-degree angle -- that indicates that the lumber was dumped."

However, most of the nails found on site are straight or curved.

"We found a few nails that were crimped, but not a lot," Quates said. "That indicates to me that there was a structure here."

Quates and his team have spent the last two years marking dig sites, where the team slowly removes dirt 10 centimeters at a time. He said he is hopeful that more mysteries will be solved regarding the historic LeRay property with the use of geophysical surveys and additional research.

Social Sharing