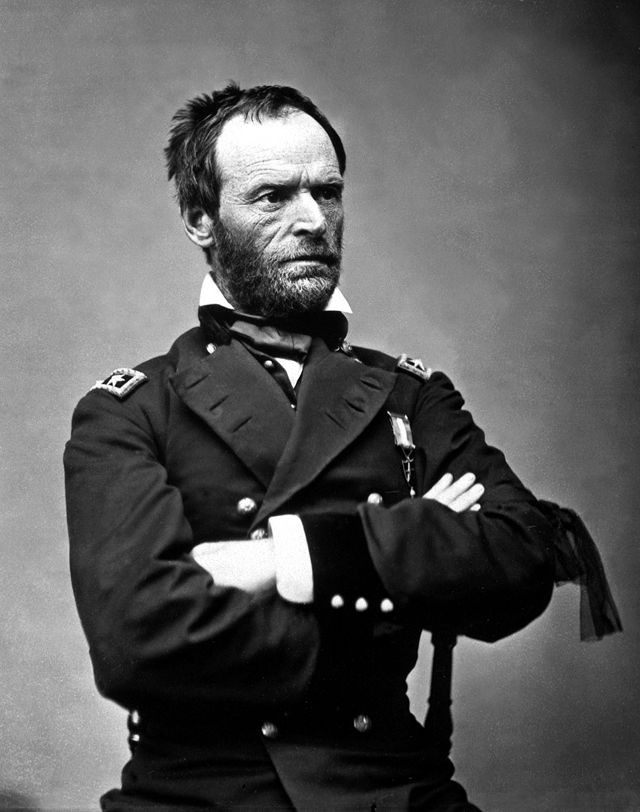

FORT LEAVENWORTH, Kan. (Army News Service, July 15, 2014) -- "War is Hell," Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman once said, but during the inter-war periods, practicing mission command can be nearly as infernal, a group of captains told the Army chief of staff.

Capt. Zebulon Pike was at the apex of his time in the Army while deployed to Iraq in 2007, for his second tour, he told Gen. Ray Odierno.

His battalion commander gave him broad latitude to use his ingenuity, initiative and discretion to do the right thing, in a setting where the mission was somewhat vague and illusive.

"The desired end state was not mentioned," Pike said. And, the commander's intent was simply, "'Zeb, you're going to Kirkuk to count barrels of oil.'"

Once there, Pike said he and his Soldiers were put in charge of securing 6.4 percent of the world's oil. In the year he was there, the oil output of the northern grid increased by 11 percent, and today, that area to the north, while not free of violence, is considered the most prosperous in Iraq.

But that's not all. Pike waded into a brouhaha between Kurdish and Sunni tribesmen, both of whom reside in overlapping areas. "We averted an outbreak of civil war through interactions and engagements," he said.

How was it possible for a junior officer to have this much mission command responsibility?

"My boss trusted me and allowed me to accept prudent risks by putting me out there and allowing me to engage and learn, even though I was not a subject-matter expert," Pike said, adding that by the time he left Iraq, he was a subject-matter expert.

If Iraq was the summit of Pike's career, his return stateside would find him in the valley.

"Upon return to the U.S., I was inundated with command and staff meetings, like the rest of my fellow captains here can tell you," he said.

The fellow captains Pike referred to were part of Solarium 2014. Seven teams, each with about 15 members, discussed issues ranging from talent management, culture, vision and branding to education and training. Pike's team was focused on mission command.

It was more than just meetings and endless reporting requirements, Pike continued. "Emphasis was on determining who did or did not complete mandatory training. Why did Staff Sgt. Jones miss his dental appointment and when is he going to make it up," and so on. In garrison, gone was the freedom of mission command.

Capt. Jason Crabtree said that increased connectivity at home station is an enabler for the kind of overbearing management described by Pike. He pointed to a zero-defect career mentality, the degree of commander preparedness, and the level of trust enjoyed between commanders as key factors in the practical implementation of mission command.

He also pointed out that the Army must culturally embrace mission command if it is to avoid bringing the environment that's prevalent at home installations along to future, real-world deployments.

"Mission command is fundamentally dependent on our ability to communicate with a great deal of trust -- trust between people and trust in information transiting the networks that facilitate our communication to make decisions," he said.

The Army needs to figure out a better way to "incentivize initiative and prudent risk taking," he pointed out.

"Humans sometimes make mistakes," Odierno wrote in Army Doctrine Publication 6-0: Mission Command, dated May 17, 2012. "Successful commanders allow subordinates to learn through their mistakes and develop experience. With such acceptance in the command climate, subordinates gain the experience required to operate on their own."

The caveat to that is that "commanders do not continually underwrite subordinates' mistakes resulting from a critical lack of judgment. Nor do they tolerate repeated errors of omission when subordinates fail to exercise initiative. The art of command lies in discriminating between mistakes to underwrite as teaching points from those that are unacceptable in a military leader," Odierno concluded in a portion of ADP 6-0.

Another area that could be improved involves performance metrics relating to readiness levels that inform mission-command decision making, Crabtree said.

Mission-essential tasks like rifle range scores and physical fitness tests are readily quantifiable, but measuring "specific kinds of human attributes that we desire" are not. For instance, he said, "no commander would tell you that his number-one private is his best marksman. He'd probably tell you it's the person who acts with a huge amount of perseverance, with candor, with honor and other intangible attributes."

A zero-defects mentality, lack of mission-command opportunities at home station, and a lack of clarity about development versus performance priorities in training, are some of the "challenges that tend to make the Army a bureaucracy more than a profession. We've got to find a mechanism to be more transparent about those requirements," Crabtree said.

A final topic of mission command involves the technology that allows commanders to execute missions.

Crabtree said he has deep misgivings about over-reliance on technology that might one day be defeated. He said preparing to operate in degraded states of connectivity is a requirement.

Fighting in a "contested cyber or electromagnetic operating environment that's being actively manipulated" by technologically savvy enemy forces will make mission command challenging, but even more important to the Army's future, he said.

Discussions regarding this should involve "re-evaluating our understanding of our almost absolute reliance on these technological enablers that are incredibly empowering," he continued.

"The pervasive use of information technology has enabled numerous efficiencies across the force, but introduced new vulnerabilities, dependencies and operational constraints which are often opaque to commanders," Crabtree said. The disruption of "unseen dependencies" can have serious consequences if commanders aren't able to readily understand the implications of a "denial of our own network."

Commanders need to "consciously think about what it means to move onto mechanisms that are totally manual," he advised. "We have to be able to transparently present the risks and dependencies associated" with modern technologies.

Crabtree and Pike then presented their working group's recommendations to Odierno.

First, there should be more interaction and communication between junior and senior leaders, Crabtree said.

"Company commanders don't often get a lot of interaction with brigade commanders. More interaction would increase learning and mutual trust. Battalion and brigade commanders can learn from their own lieutenants and captains," he explained, if they protect time to do so by giving junior officers white space on their calendars.

So, in a sense, this informal mentorship can work both ways and more trust would undoubtedly result in more openness to allowing prudent risk-taking in mission command, he added.

Existing multi-source feedback tools could be used to make this process transparent and capture basic data and perceptions about commanders' ability to develop their subordinates, he said.

Next, the Mission Command Center of Excellence at Fort Leavenworth should try to better define qualitative and quantitative performance metrics. Qualitative metrics might focus on performance attributes like perceptions of judgment, initiative and so on. Quantitative metrics might use objective measurements such as the ratio of specified tasks given by higher headquarters to the key implied tasks required by junior leaders.

"The Army should aid commanders at all levels by publishing planning guidance with notification timelines, deadlines, and frequencies for directed mandatory training -- provided as a histogram," Crabtree said, providing an example.

This data would aid the institution and more senior commanders in protecting "white space" to provide scheduling flexibility and help improve consistency for company-grade officer- and non-commissioned officer-led developmental and performance initiatives on the training calendar.

In another suggestion, Crabtree said the Mission Center of Excellence should add a formal requirement to its philosophy or warfighting function to highlight commanders' responsibility to communicate their development, versus performance priorities to subordinates. This will help to underscore appropriate opportunities to create the teaching points referenced by Odierno in his introduction to ADP 6-0, Crabtree said.

Crabtree then explained the difference between developmental versus performance priorities, using two examples common to home station training. A developmental opportunity might be giving a brand new platoon leader a chance to run a complex live-fire range during a field exercise. If the training were internal to the company, a greater degree of flexibility would allow for learning, with minimal impact to mission.

A performance priority would be an event where there's a lot less room for risk or error. An example might be running a battalion-level gunnery exercise that would contribute to a unit's combat-ready certification, with limited time and many specific requirements.

In this instance, there might be fewer opportunities for the lieutenant to learn through trial and error, and it would probably best executed by a more experienced junior officer. Crabtree noted that "commanders who clearly communicate development versus performance goals will be more successful in creating the culture of learning and experimentation needed by our Army."

Next, U.S. Training and Doctrine Command and U.S. Army Forces Command should develop a comprehensive plan to understand the risks to mission accomplishment that stem from "interdependence in the modern networked force," Crabtree said.

This process will help the Army by identifying shortcomings in doctrine and technology by leveraging performance information gleaned from training events at home station through mission-rehearsal exercises at the combat training centers, he said, adding that practicing with a wide range of network conditions and enablers will help prevent unchecked over-reliance on complex and vulnerable technologies as we move toward Force 2025.

Pike offered another suggestion to incentivize junior officers to take prudent risks.

The final suggestion Pike gave was to rotate units or individual Soldiers out of the U.S. as often as possible, an idea that's in sync with regional alignment.

For example, "increase temporary duty assignments to observe multinational partners and their innovative mission command techniques, tactics and procedures, rather than doing a permanent change of station to a 'broadening assignment,'" he explained.

(Editor's note: This is the third article in a four-part series on Solarium 2014. The final article will discuss suggestions made at the solarium in the areas of education and training. For more ARNEWS stories, visit http://www.army.mil/ARNEWS, or Facebook at www.facebook.com/ArmyNewsService.)

Related Links:

Mission Command Center of Excellence

CSA taps captains for talent-management ideas

Texting no substitute for face-time, captains tell CSA

Social Sharing