Today, properly caring for the human remains of fallen Soldiers is considered one of the military's most important duties. Yet this was not always the case. Standards for care have evolved steadily since the 19th century. During the years between the Spanish-American War and the close of World War I, many dedicated Soldiers, most notably Chaplain Charles C. Pierce, engineered a critical transformation in the Quartermaster mortuary affairs mission and culture.

EARLY CARE FOR SOLDIERS' REMAINS

Before the Civil War, many frontier posts maintained a cemetery for their Soldiers, but they had few provisions for the proper burial of Soldiers who died in a campaign. When the United States created a cemetery for Soldiers who died in the Mexican-American War, procedures were so poor that not a single body was identified.

During the Civil War, attitudes shifted toward providing better care for the war dead. These men had given their lives for the nation, and both Soldiers and civilians believed they deserved a decent burial.

In July 1862, Congress authorized a national cemetery system to be operated by the Quartermaster General. This act is considered the beginning of the quartermaster mortuary affairs mission. Unfortunately, the act merely authorized the cemeteries. The Army lacked the organization, doctrine, and procedures to identify human remains and provide timely burials.

Only 60 percent of the Union Soldiers who died in hospitals and on the battlefield were identified. A Soldier who died on the battlefield had a much lower chance of being identified, especially if he was on the losing side of an engagement. In fact, so many casualties were left on the battlefields that the Army searched from 1866 to 1870 to find fallen Soldiers and bury them, usually as unidentified.

PROCEDURES ESTABLISHED IN CUBA

In 1898, the United States went to war with Spain to end Spanish rule over Cuba. As a result of that war, the United States acquired the Philippine Islands and began a prolonged conflict with the Filipinos, who desired independence. The experience of overseas fighting in Cuba and the Philippines produced major changes in the procedures for handling the remains of fallen Soldiers.

In Cuba, Army regulations prescribed some minimal procedures for care of remains by the Soldiers' units. Casualties in Cuba were placed in temporary graves to be exhumed and returned to the United States after the fighting. Procedures specified that the units place identification information in a bottle to be buried with the Soldiers. Timely identification by the unit was essential to the process.

The Quartermaster Department employed a burial corps, consisting of civilian morticians working under contract, to exhume and return the remains of casualties from Cuba. With the new procedures in place, the identification rate rose to 87 percent.

IDENTIFYING HUMAN REMAINS

Although the burial corps also operated in the Philippines under contract with the Quartermaster Department, the most important developments came in the Philippines within the U.S. Army Morgue and Office of Identification in Manila. In response to the commanding general's request, Chaplain Charles C. Pierce took charge of the morgue and instituted procedures that dramatically improved the management of Soldiers' remains.

When he assumed responsibility for the morgue, Chaplain Pierce faced the problem of identifying human remains scattered in temporary graves around the Philippines. He established a process of collecting all available information regarding the possible identity of these casualties, such as the approximate place of death, the Soldiers' physical characteristics, the nature of the wounds if known, and any other information that might provide a clue.

He then began exhuming bodies that were often weeks or months old and comparing the human remains with the available information on potential identities. By comparing the information, he achieved the previously impossible task of identifying all of these Soldiers. This marked the beginning of modern identification procedures.

Responsibility for the human remains did not end with identification. Pierce also ensured that each Soldier received a new uniform for burial. With the aid of some of his Soldiers, he pioneered techniques for embalming human remains in the tropical climate.

In time, however, the combination of hard work and tropical climate left Pierce too sick to remain in the Philippines, so he returned to the United States. In 1908 the lingering effects of duty in the Philippines resulted in his retirement from the Army, and he resumed his career as an Episcopal minister.

DOG TAG CONCEPT BORN

As he left the Philippines, Pierce made one last recommendation: All Soldiers should be required to wear identification tags. Those tags became famously known as "dog tags." Since the Civil War, Soldiers had frequently purchased some form of identification to be worn around the neck. Pierce recommended that instead of Soldiers voluntarily purchasing the tags, the Army should provide aluminum disks and require their use.

In his final report to the Adjutant General, Pierce noted, "It is better that all men should wear these marks [ID tags] as a military duty than one should fail to be identified." By World War I, the dog tag was widely accepted, and it has been standard Army practice ever since.

GRAVES REGISTRATION SERVICE

After the Quartermaster Department changed to the Quartermaster Corps in 1912, military units could be organized to provide necessary services that had previously been contracted. As a result, military units would eventually replace the contracted burial corps.

As the United States watched Europeans fight during World War I, it realized that entering the war would result in massive casualties and the need for a system to handle human remains. On May 31, 1917, less than two months after the United States entered World War I, the Army recalled Pierce to active duty, this time as a major in the Quartermaster Corps.

Because of his experience in the Philippines, the Army placed him in charge of the emerging Graves Registration Service for the war. Subsequently he rose to full colonel (with an administrative reduction to lieutenant colonel after the war).

The Graves Registration Service was established in August 1917, and Pierce arrived in France in October. His organization initially consisted of only two officers and approximately 50 enlisted personnel. From this nucleus, the organization grew to 150 officers and 7,000 enlisted personnel in 19 companies. Over the course of the war, the organization supervised more than 73,000 temporary burials. These initial graves registration Soldiers established how the service would operate during major conflicts.

Like so many logistics functions, graves registration seemed simple in theory but was complicated in practice. Because the Army lacked the assets to transport human remains back to the United States, casualties were placed in temporary graves until after the war. Timely identification and burial was considered the key to ensuring correct identification of the Soldiers.

Combat units performed much of the labor, with graves registration personnel assisting the units and recording all temporary burials. In addition to religious services, the unit chaplains typically helped to record the necessary information.

The French government purchased the land for temporary cemetery sites on behalf of the United States. This process required careful coordination. The French wanted to avoid graves located near water supplies or heavily trafficked areas. When combat conditions produced isolated graves or small clusters, the rules were frequently ignored.

DEVELOPING IDENTIFICATION PROCEDURES

In practice, the work proved to be more complicated than expected. With no comparable experience to work from, the Soldiers in France had to create their own procedures. For example, since there was no standard grave marker, Pierce and his staff decided on a simple cross for Christian Soldiers and a Star of David for Jewish Soldiers. The identification information was to be recorded carefully and placed with the grave marker.

The graves registration Soldiers needed to design and create forms for documenting their activities. In theory, the deceased received temporary burials at locations far enough from the battlefield to allow the graves to remain undisturbed in temporary, reasonably large cemeteries for the rest of the war. In reality, combat conditions frequently produced burials in isolated graves or in very small plots. Often the graves were shallow or improperly prepared. Artillery or troop movement could disturb the grave and the identification information.

Identification of the human remains relied heavily on the units' ability to identify their own Soldiers in a timely manner and on the new dog tags, which had been adopted as standard issue in 1913. When necessary, however, the graves registration personnel used the procedures of comparing physical characteristics to known information, which Pierce had pioneered in the Philippines. Their work resulted in a 97-percent identification rate--something previously unimaginable for battlefield deaths on such large scale.

POST WAR OPERATIONS

After the hostilities ended, the work of the Graves Registration Service entered a new phase. First, the graves registration personnel needed to relocate the human remains of the Soldiers to a manageable number of locations since the human remains of more than 70,000 Soldiers were scattered in 23,000 burial sites. After extensive searches and labor, the Army moved the human remains into 700 temporary cemeteries to await final disposition.

Next, the United States resolved the issue of closing the temporary cemeteries and moving the deceased Soldiers to their final resting places. After much discussion, the War Department decided to place the decision with the families. Families could chose burial in an overseas U.S. cemetery, in a government cemetery in the United States, or in a private cemetery. In the first two options, the government paid all the costs. In the last option, the family provided for the cost of the private burial plot.

OVERSEAS CEMETERIES

Overseas, the United States obtained eight permanent cemeteries, one each in Great Britain and Belgium and six in France. Until the American Battle Monuments Commission was established in 1923, the Quartermaster Corps developed and maintained these cemeteries. To this day, these cemeteries are impeccably maintained by the American Battle Monuments Commission.

From 1930 to 1933 the Quartermaster Corps sponsored the visits of widows and mothers of the casualties to the overseas cemeteries.

DISPOSITION OF HUMAN REMAINS

Transferring human remains to the United States presented an entirely different set of problems, especially within a war-ravaged nation. Exhumation required careful observance of French health regulations, especially for Soldiers who died from disease. Transportation of the human remains required close coordination with France and Belgium to manage scarce transportation resources and allow the Europeans to render a last salute to the American casualties.

Inevitably, thousands of requests for exceptions to policy were received and had to be decided individually. Parents living in Europe often requested the transfer of remains to their own homeland. Marines who fought and died with the Army were managed according to Department of the Navy policies. In cases where the grave markings were disturbed by combat or other activities, the Army needed to verify the identity of the human remains.

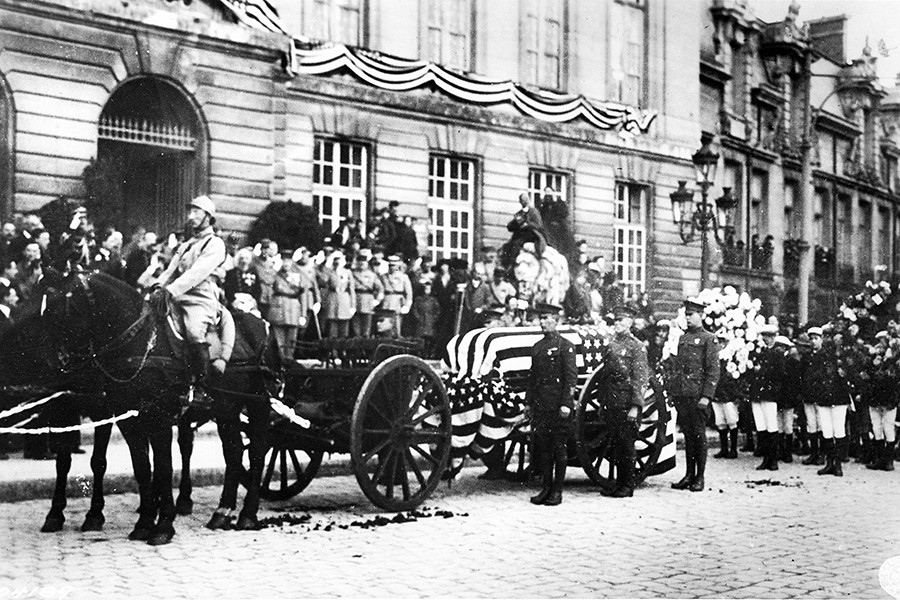

Following the example of France and the United Kingdom, the United States decided to honor all of its war dead by placing one unidentified World War I Soldier into a special tomb at Arlington National Cemetery on Nov. 11, 1921. This became the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

PIERCE'S FINAL CONTRIBUTIONS

Pierce remained in France until July 1919, when he transferred to Washington D.C. to take charge of the Cemetery Division of the Office of the Quartermaster General. From there he continued to direct the work of moving the remains of U.S. Soldiers to their final resting places.

In May 1921, Pierce and his wife went to France with members of the National Fine Arts Commission to oversee the development of the U.S. cemeteries. While in France, both Pierce and his wife died from illness within three weeks of each other.

In June 2013 Charles C. Pierce was inducted into the Quartermaster Hall of Fame in recognition of his pioneering work in graves registration.

The Army changed the name of the Graves Registration Service to Mortuary Affairs in 1991. During the century since World War I, much has changed in the Army's mortuary affairs procedures. The practice of temporary overseas burials ended during the Korean conflict when the communist counteroffensive overran some cemeteries and threatened others. It was better to return the remains during the conflict than to risk having remains fall into enemy hands. By the Vietnam War, Air Force transportation could return the remains of fallen Soldiers within days.

Modern technology has established a standard for 100-percent identification of American service members killed in recent conflicts, yet the professional ethos established in the early years remains. The United States makes every reasonable effort to ensure that the remains of fallen service members are recovered and returned with all due respect and care.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Dr. Leo Hirrel is the Quartermaster School historian. He holds a Ph.D. in American history from

the University of Virginia and a master's of library science from the Catholic University of America. He is the author of several books and articles.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

This article was published in the July-August 2014 issue of Army Sustainment magazine.

Related Links:

Browse July - August 2014 magazine

Army Sustainment Magazine Archives

Social Sharing