WATERVLIET ARSENAL, N.Y. -- The Watervliet Arsenal's apprentice program has since 1905 produced some of the finest machinists in the country. But despite such a legacy, today's apprentices may face a burden that their predecessors may not have experienced.

For more than 100 years, the apprentices have helped build the 16-inch cannons that once graced America's battleships during World War II to manufacturing engineer bridges for U.S. troops who were fighting in Vietnam.

But given an era of fiscal uncertainty in today's defense budget process, the challenge that apprentices face today may be unprecedented as they must be more adaptable and responsive than their predecessors to ensure that the arsenal retains its critical skill base.

The arsenal's workforce has ridden the ebbs and flows of military budgets since the War of 1812. As wars ramp up, the demand for the large caliber manufacturing rises in direct proportion to the urgent needs of our war fighters. When wars wind down, the demand for the arsenal's products decreases almost as fast as the troop withdrawal. As demand decreases, so often does the size of the arsenal's workforce.

During World War II, the arsenal's workforce peaked at more than 9,300 employees. By the end of the war, the arsenal was down to 1,756 employees. Prior to the first Gulf War in 1991, the arsenal had nearly 2,000 employees. By 2002, the numbers were below 500. When simultaneous combat operations in Iraq and Afghanistan were ongoing just a few years ago, the arsenal's workforce numbered nearly 640. Today, the arsenal stands at just over 500.

Someone who simply looks at personnel numbers, however, may arrive at a false sense of the level of capability and capacity the arsenal has to support the war fighter. Although the arsenal stands at just over 500 personnel, it does not mean the arsenal cannot provide full-spectrum manufacturing support as it did just a few years ago ̶ because it must.

Which leads to why the arsenal leadership does not look so much at the numbers of machinists, but in the level of critical skills, in essence capability, as well as capacity the arsenal retains at any one time. Although the arsenal has only 85 machinists today, they still must provide the same machining capability as when their numbers were significantly higher just a few years ago.

After all, the Army leadership expects the arsenal to manufacture cannons for tanks and for howitzer systems, as well as tubes and associated parts for the 60mm, 81mm, and 120mm mortar systems. Those are the arsenal's core missions and have been since 1887.

Today's low personnel numbers, which are driven by lower workload requirements, have implications. If the arsenal wishes to ensure its long-term viability, it must quickly adapt to make certain that it retains the critical capabilities to support the needs of the war fighter regardless of the size of the workforce.

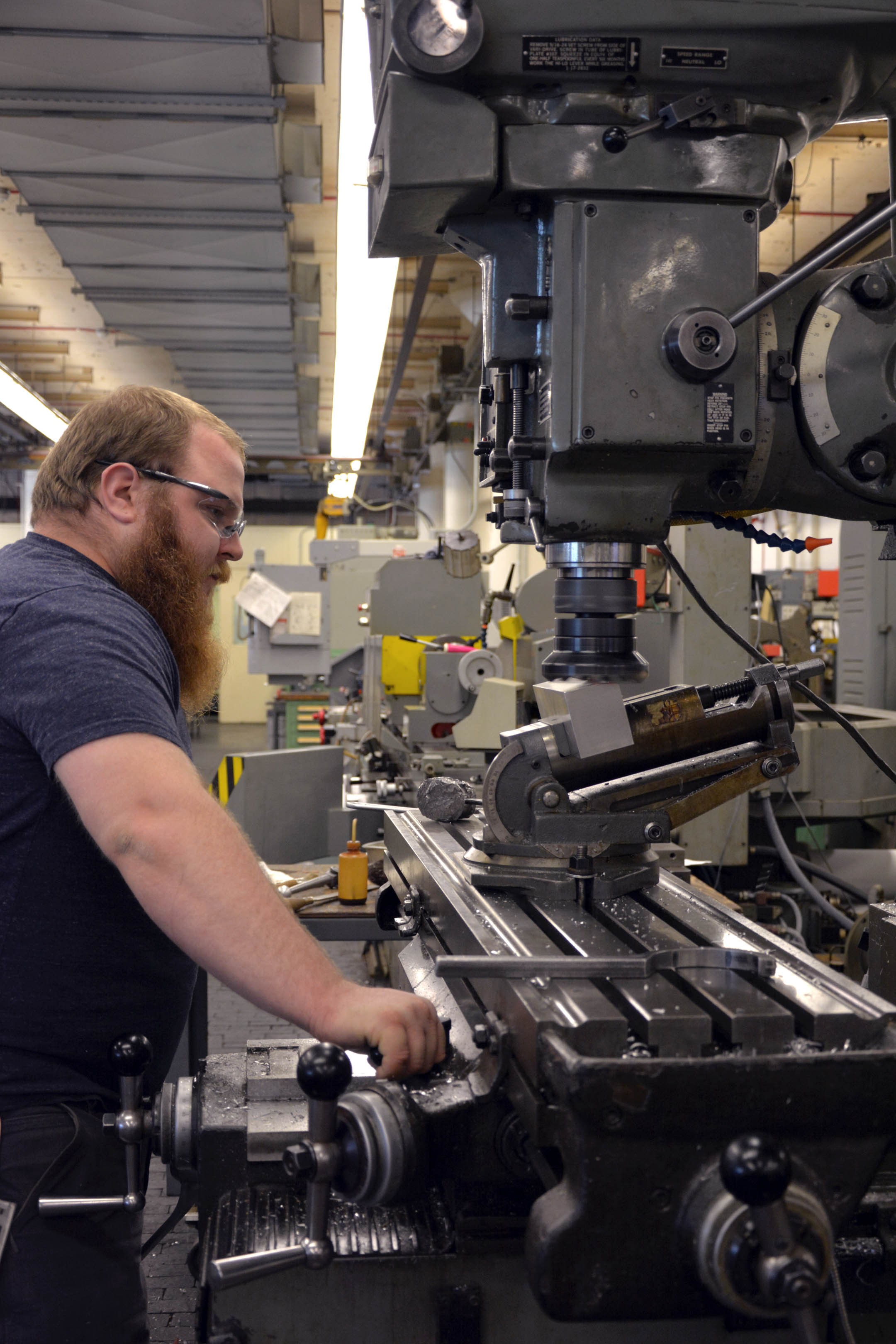

One way the arsenal is adapting today is by bringing on line more computer-numerically controlled machines. Nearly $26 million in new capability will be brought on line this year and many of the new machines will perform multiple operations, whereas the former machines may have been able to perform only one operation. This allows for a significant reduction in set-up time for a machinist.

As important as new machinery is to the arsenal's long-term viability, so too is the increased scope of responsibilities for the arsenal's future machinists. The days of specializing in just a few operations of a product line for years is over as today's apprentices will be expected to work a variety of operations on several product lines to make up for fewer machinists on the arsenal's production floors.

The apprentices must become part of the solution as to how the arsenal will retain an adequate level of critical skills despite the reduction in personnel that the arsenal has experienced in recent years.

Terry Van Vranken, the arsenal's apprentice program supervisor, said that today's apprentices, who number 14, must be able to run any one of the 600 machines that reside on the arsenal upon their graduation from the program.

Van Vranken has looked into the future and said that he does not believe the workforce will grow much in size beyond the current manning levels and so, he is challenging his apprentices to do more than was required of apprentices when he was in the program 10 years ago.

"Even with a smaller workforce, we still need to retain the critical skills to manufacture large caliber weapon systems and their component parts," Van Vranken said. "After all, Soldiers don't care if the arsenal has 500 or 1,000 workers as long as they get a high-quality artillery or tank cannon on time."

Van Vranken said that by the end of the first year of training, today's apprentices are already machining products with little direct supervision. And, by the end of their fourth year, the apprentices will not only be machining complex operations independently, they will also be charged with training senior machinists on advanced machining.

James Nowell and Jeremy Brackett are two apprentices who are in their second year of the four-year program. Despite their short tenure, it seems that they fully grasp the awesome responsibility that is about to bestowed on them.

Nowell, who grew up just outside the arsenal's fence line, said he loves the challenges that are now being afforded to him as an apprentice.

"We understand that as the workforce numbers decline that we must take on more responsibility, accomplish more, and be ready to machine to tight tolerances on any one of the 600 machines at the arsenal," Nowell said. "I fully understand that upon graduation, where I machine on the arsenal isn't so much about where I want to go, but what the Army needs me to do, and I accept that."

Brackett said that he has always been mechanically inclined and took that passion into the U.S. Navy where he served five years on active duty as an aviation mechanic. Armed with military experience and a natural mechanical ability, becoming a machinist has turned out to be a win-win situation for him and for the arsenal.

"The hiring for our apprentice class was exceptional because the 14 guys who are currently in the program are similar to me in that they have strong mechanical backgrounds," Brackett said. "I feel pretty good that we will meet the challenge upon graduation because we are already doing machining operations that are more complex than where we should be in the program."

Given the continued fiscal uncertainty in the defense budget due to sequestration ̶ which caused the apprentices to be furloughed in their first year in the program ̶ one might think that keeping these apprentices motivated to stick it out with the Army would be a challenge.

But, according to fellow apprentice Colin McCarthy, that does not seem to be the case.

"Yes, furloughs financially hurt us because many of us gave up better paying jobs to become an Army apprentice," McCarthy said. "But what makes our class so strong is that each of us has a high sense of personal motivation and a commitment to the arsenal and so, we will do well no matter the challenge."

As the arsenal leadership fully understands, critical capability isn't purely about numbers, it is also about the skill level, experience, and adaptability that the remaining workforce has to meet the needs of our military.

Despite the arsenal leadership not solely looking at personnel numbers, the fact remains that numbers do influence the long-term viability of the arsenal. The arsenal's only feeder program for talented machinists has only 14 apprentices. Those numbers mean something.

The apprentices undergo a challenging 8,000 hours of hands-on training at the arsenal and four years of schooling at the Hudson Valley Community College in Troy, N.Y. This current class is in its second year of the program and will graduate in August 2016.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Watervliet Arsenal is an Army-owned-and-operated manufacturing facility and is the oldest, continuously active arsenal in the United States having begun operations during the War of 1812. It celebrated its 200th anniversary in July 2013.

Today's arsenal is relied upon by U.S. and foreign militaries to produce the most advanced, high-tech, high-powered weaponry for cannon, howitzer, and mortar systems. This National Historic Registered Landmark has an annual economic benefit to the local community in excess of $100 million.

Related Links:

Story: Instilling Soldiers' confidence in their weapon systems is a 200-year tradition at Watervliet

Story: From Benjamin Franklin to Watervliet, the spirit of volunteerism is alive and well

Watervliet Arsenal Flickr Page

Watervliet Arsenal Slideshare Page

Watervliet Arsenal YouTube Page

Social Sharing