Army AL&T talked with Maj. Gen. William C. Hix, ARCIC deputy director and chief of staff, who came to TRADOC and ARCIC after serving in Afghanistan as the director, Future Operations, International Security Assistance Force Joint Command. He has also served in a variety of strategy and planning positions, including director for operational plans and joint force development, Joint Staff J-7; and Strategy Division chief, Joint Staff J-5. He graduated from the United States Military Academy (USMA) in 1981. He holds a Master of Military Art and Science, was a National Security Affairs Fellow at the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace at Stanford University and is a member of the International Institute for Strategic Studies.

Joining Maj. Gen. Hix were Col. Christopher G. Cross, chief of ARCIC's Science and Technology (S&T) Division, and Col. Kevin M. Felix, chief of ARCIC's Future Warfare Division. Cross earned a Ph.D. in physics from the Naval Postgraduate School and a Master of Strategic Studies at the U.S. Army War College. He has served as a Defense Threat Reduction Agency Stockpile associate to the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) and has taught physics at USMA. LLNL sponsored his doctoral research on modeling of the spatial distribution and temporal decay of geomagnetically trapped charged particles following a nuclear detonation in space.

Felix, an Army field artillery and foreign area officer, is a graduate of the Defense Language Institute's Greek and French courses and the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College. He also graduated from the International Training Course in Security Policy of the Graduate Institute of International Studies, Geneva in Switzerland. He holds a bachelor's degree in civil engineering from USMA and a master's degree in international relations from the University of Geneva. He recently completed studies as a National Security Fellow at Harvard University's John F. Kennedy School of Government. He came to ARCIC from a brigade command with the 4th Battlefield Coordination Detachment, Shaw AFB, SC. He served in the 101st Airborne Division and deployed to Operation Iraqi Freedom, serving as the division's fires coordinator during the invasion of Iraq.

In talking with Hix, Felix and Cross, Army AL&T learned more than we expected.

Army AL&T: How does ARCIC envision the future and then hand that off to the acquisition community to implement?

Maj. Gen. Hix: Certainly since I came into the Army, this is the third major period of change that has been undertaken in a period of declining resources. I became a member of the Army in the late '70s, when we were coming out of Vietnam and there was a significant manpower reduction and budget cuts. And yet at that time, we laid the groundwork for the defense buildup that was undertaken in the 1980s and resulted in what we call Division 86 or the AirLand Battle Army with the Big Five: the Abrams M1 tank, the Bradley Fighting Vehicle, the Black Hawk and Apache helicopters, and the Patriot missile system.

And a host of other things [happened during that time] in terms of leader development and training. We instituted the combat training centers. So it was truly a significant integration of the acronym DOTMLPF, what we call the imperatives that you have to keep in balance--doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leader development, Soldiers (personnel) and then, of course, facilities. Because if you improve, say, the lethality of a combat platform, you have got to actually have a range that can handle the gun.

So you've got to keep all those things in balance. And that is what TRADOC does. In fact, that is why TRADOC was formed. Because coming out of Vietnam and with the wake-up call of the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, we found that we were out of position across all of those imperatives, and particularly our combat platforms. Our doctrine organizations weren't really optimized to deal with the very high tempo and exceptionally lethal battlefield that we saw in that war.

As we came out of the Cold War, and following the very successful operations in Panama and Desert Storm, we also again went through a very significant force reduction and budget cut. And yet, during that same period, we substantially modernized our ground vehicle fleet with the M1A2 SEP [M1A2 Abrams tank System Enhancement Package], which had the hunter-killer system on it that really increased the effectiveness of that combat platform by at least an order of two, if not better; the Desert Storm variant of the Bradley; the [AH-64D] Apache Longbow, etc. Although those are all very important and played a strong role in our operations in the last decade, 2000 to 2014, as importantly, we began to posture ourselves to think differently about how we operate in the Information Age.

And we began with [then-Army Chief of Staff] Gen. [Gordon R.] Sullivan's charge to conduct what we called the Louisiana Maneuvers Task Force, where we learned about how to experiment and think about operating differently in the 21st century. And we transitioned that into a program I think you're familiar with, Force 21, centered on the 4th Infantry Division, to how we digitize our ground forces and better integrate the promises of the Information Age into ground combat so that we got more out of a smaller but still very capable and lethal Army.

That process has continued through to today. That's really where we learned about how to think about the question that you asked--how do you think about a 30-year modernization process? Particularly when you consider that you have the ?nonmaterial solutions that are as important as, if not more important than the material solutions as you go forward. We should remember the French had a better tank in the opening stages of World War II, but they had the wrong idea and lost their country for several years because of that.

This integration of thinking about the future, getting ideas, surveying deep, pulling those into concepts, looking at those concepts against the emerging security environment and demands of the nation's strategies, … looking at where the gaps are, coming up with required capabilities that drive change across those imperatives of DOTMLPF--that is really ARCIC's role, and then physically changing the Army over time. It is a constant process of adaptation in the near term, evolution in the mid-term and innovation in the far term. We own the centerpiece of that, from the far term into the near-term adaptation piece. And obviously, we connect into a variety of partners across the Army and then into industry, academia, other parts of the government, etc.

Army AL&T: What do you see as ARCIC's role in a 30-year modernization process? On your website, you describe Force 2025. What do you think the force of 2025 would look like?

Maj. Gen. Hix: Col. Kevin Felix leads that deep futures piece with our Unified Quest study program that we run for the chief of staff of the Army. And then Col. Cross--Chris Cross--runs the science and technology piece, which really spans the far and mid-term and bridges into, in some cases, the near term.

What would we look like in 2025? Physically, we will probably look very similar to what we do today. The challenge for the Army is to retain as much capacity as possible. [Chief of Staff of the Army] Gen. [Raymond T.] Odierno was interviewed by the Council on Foreign Relations and talked about the relative balance--the impacts of end strength in terms of how we manage the force or the challenges of the environment as we see it, with a force of 450,000 in the active force and 980,000 across the active, Guard and Reserve. And he said, "Do I think we can do it? Yes. Will there be risks? Yes. But we think we can do it." (To read the entire Feb. 11 conversation, go to http://www.cfr.org/united-states/amid-tighter-budgets-us-army-rebalancing-refocusing/p32373.)

But then he talked about the impact of that next step down, from 450,000 to 420,000 and about 920,000 across all three--again, active, Guard and Reserve. And he said that reduction, which is about 60,000 across the entire Army, active and reserve, was a significant dropdown. And I think what's important to realize is we did the reorganization and shaping of the Army to the program we call Army 2020 as we've come out of Iraq and are drawing down in Afghanistan. We've retained the vast majority of our combat power. We deliberately trimmed overhead, brigade headquarters, sustainment structure and those sorts of things.

And so, in general, the punch of the Army at 490,000, and a little over a million across the active, Guard and Reserve, is very similar to the Army that we've had for the last decade--a very substantial, very capable Army in terms of its combat power. A lot of churn, obviously, within units as they draw down, but nonetheless, the resulting product in 2015 will be very significant in terms of its abilities to respond to crisis and, frankly, finish major theater conflicts if we happen to wind up in one.

As we come down below that level, we're going to see real reductions in combat power--not marginal reductions, but real reductions, because we're going to actually have to cut combat forces out of the Army.

Col. Felix: As Maj. Gen. Hix mentioned, I run the chief's future study plan, which is called Unified Quest, and it really is about scouting the future through a series of seminars, symposia [and] war games. We typically have a major war game once a year, sometimes twice. That brings the community together. Our sister services come, [and it's] interagency, multinational in a big way. We expose them to various ideas that we're thinking about--get this greenhouse of ideas going about future ways to operate.

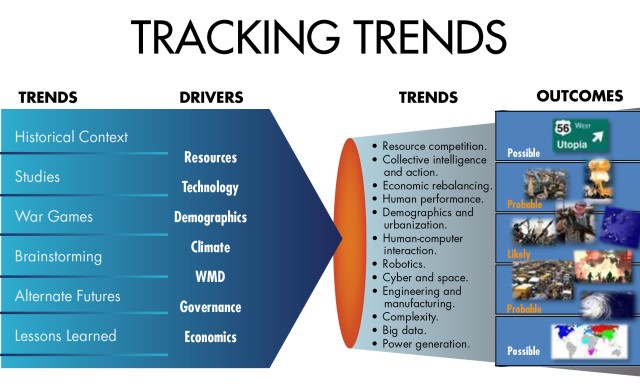

It all starts with the environment. What do we think this operational environment will be in, say, 2030-35? And so in order to get there, we look at trends. (See Figure 1.) We do some strategic trends work; we monitor those trends with our TRADOC G-2. So we understand what it might look like in terms of that. We may not get it right, but at least we follow the trends. One of the trends we're following this year is this idea of rapid urbanization. So in our war game this year, we will focus on a megacity in 2035. That will be the framework and the backdrop.

The next piece of it is our strategy during that time period. How has it evolved? What are the vital interests of the United States with respect to the rest of the world, such that we will commit blood and treasure to something? And we have to make it plausible. So we bring in the intelligence community. We share our potential scenario with them because we can't just be creating our own ideas. We have to say, in conjunction with the intel community, what's plausible in that environment.

We set those conditions, and we build that environment. We allow our sister services to come in and participate with their emerging technologies and objectives so that we can achieve something as a joint team, the Army as a joint team fighting in that particular environment or doing whatever is required. You know, it could be humanitarian assistance, disaster relief, major combat--the full range of military operations.

That's the setup. Our job is not to win in these games, but to see where we're brittle, see where we break, and then look for gaps. And then we find solutions to those gaps. I'll turn it over to Chris to talk a little bit about that.

Col. Cross: If you look over the last decade, we've taken the eye off the ball from the S&T perspective in terms of the future, and we've done it deliberately and for the right reasons. The S&T community has focused on providing the men and women in combat the capabilities that he or she needed. But we have not looked deliberately at the capabilities we need to develop in the future--2025 and beyond--and made the right investments to get us there from here. And so in order to understand where we need to go, we need to understand where we are.

We look very deliberately at the way we manage our current fundamental research investments. What we found was that about 95 percent of what we do today was focused on the near-term gaps, those things within the POM [program objective memorandum cycle] … but it has put us at a disadvantage, almost a lost decade. So coming out of war, transitioning, we are looking very closely at the capabilities we need to develop for the future force, 2025 and beyond.

The capabilities we're after are a leaner force, which means a unit that's able to do more than a current, like unit can do today. We want to increase the capability and lethality of those units, extend the operational reach of all units--squads, platoons, companies, battalions and BCTs [brigade combat teams]--all underpinned by the necessity to prevent overmatch. The threat has had an opportunity to watch the United States and our allied partners bare our soul to the world in terms of capability, and to identify those things that we do really well and the things that are potential vulnerabilities. And, therefore, they are investing in those areas that are potential vulnerabilities.

If you look at the future and the capabilities that we need, we have to account for the fact that the threat has identified things we may be vulnerable at in terms of technology or capability or doctrinal areas, and they're focusing their investments on those areas. By 2025, we're going to set the conditions with a leaner, more capable force to truly, fundamentally change the Army as we move deeper into the future and the decade of the '30s.

Maj. Gen. Hix: Let me just reinforce one thing: If you look at the U.S. Army, every time we've been in one of these periods of resource reduction, that's where all the ideas have been generated. I think the only time we had a dearth of intellectual engagement was probably right after World War II, and the Army was consumed in load-shedding 9 million people.

Army AL&T: Col. Cross, you mentioned that you're building this for 2025 and the decade of the 2030s, and that will allow for fundamental change in the decade of the '30s. What do you think that fundamental change would be? What do you see in the future?

Col. Cross: Let me talk just from a science and technology perspective, and then we'll talk about how we'll operate differently. First of all, one of the constraints that we have is the weight of our vehicles. And if we still have a 74-ton tank in 2035, we'll still have a very difficult time deploying a capability along with an operationally significant force in order to turn the tide of events. And so one of the areas that we do need to focus on is developing a lighter tank. It's going to require significant material sidestepping, as well as all the other components to get to a much lighter, deployable and agile tank.

Another aspect is what we call the big data or data management problem--getting information to the point of need at the speed of war. Right now in Afghanistan, many of our Soldiers in contact are getting information through the same type [of] handset that their grandfather fought with and received information from in World War II. We owe them better than that. And so the data's out there, but we have to find a way to get the relevant information to the Soldier so they're not surprised like they are in Afghanistan. Seventy to 80 percent of the time in contact in Afghanistan today, Soldiers are surprised. We owe them better, and that's part of changing the way that the Army fights so that we're not surprised.

We're also looking at weapon systems that will not only apply the kinetic energy capability, but also directed energy--lasers, high-powered microwaves, other capabilities that extend the operational reach of the battlefield from a science and technology perspective.

The final comment I'll make is on human performance and optimizing the Soldiers that we have. As we become a smaller Army whose units are leaner and more capable, it puts a lot of burden on the leadership and the Soldiers to do more than we've ever asked them to do in the past. So we need to look for ways to maximize their training efficiency, the physical, cognitive and social development of the Soldiers, to enable them to make very difficult, very complicated decisions in a world that we can't imagine even today, at the same rank structure in which we expect folks to make those decisions now.

In Afghanistan, we'll be awoken at 1 in the morning to make decisions on whether or not certain types of assets could be used against targets, because we've not developed the Soldiers and the leaders at the lower levels to make those decisions. We have to get through that.

Maj. Gen. Hix: When you take into account the trends that Kevin Felix talked about and you look at how those things play out over the next 20 years, there's a really unfortunate convergence in the decade of 2030 to 2040 in terms of urbanization, in terms of growth of populations, where those populations are expanding, with 90 percent of the population growth in the developing world.

If you read Eric Schmidt [and Jared Cohen's] book, "The New Digital Age," they make the observation that revolutions will occur more rapidly and more frequently in the future. Conversely, they also note that it is unlikely that the speed at which things come apart will also be replicated by the speed at which things can be put back together again. So, in other words, it's very easy to break Humpty Dumpty, but it's really hard to put him back together again. You see manifestations of this in the Arab Spring and its aftermath right now, and the instability in all those countries.

You take that into account, you look at the survey of the world, you look at who's going to be the principal arbiter in terms of trying to solve these problems, and it's quite likely going to be the United States. The French have done a study out to 2040, and one of their conclusions is that the United States will still be the principal power in the world.

You look at our force structure going down and the challenges that this environment poses--the speed of action, the speed at which events unfold, the second- and third-order effects rippling through a more tightly coupled international, geopolitical and economic environment, and it's going to demand that we be able increasingly to influence events at speed with forces that can actually arrest the acceleration of events and direct them in other ways.

This [calls for] an operationally significant force that can get there quickly and rapidly influence those events--in some cases, preventing them or precluding escalation, which is what we really want. One of the reasons the Army exists is to prevent bad things from happening. We want to deter people from stepping across red lines, declared or otherwise.

Army AL&T: On your website, you have "revolutionary," "game-changing" and "leap-ahead" technology. So in ARCIC's view, what would you envision as "revolutionary," "game-changing" and "leap-ahead"?

Maj. Gen. Hix: Well, certainly quantum computing would be one of those areas where potentially, if your adversary does not have quantum also, you could take apart their encryption systems. You'll have unbreakable codes. You'll be able to process data and present it in ways that we currently can't, which kind of touches on the things that Col. Cross was talking about with the human factors and the ability to present information to people at lower levels.

We think the ability to connect those kinds of information technology together, to give ground Soldiers the kind of situational awareness that we're striving to achieve with the F-35 for a pilot, is an exceptionally important area. And that would be revolutionary. We'll take a fighter pilot's taxonomy, we won't use a Soldier's: If you look at [the late Air Force Col. John R.] Boyd's hierarchy, it starts with people, then ideas, then materiel or technology. His focus was on the fighter pilot; ours is on the leader. And right now we equip fighter pilots and others--ship's captains, carrier strike group commanders, people like that, with exceptionally well-integrated information environments.

The Army is getting better at integrating those at the strategic and theater level; the operational level; division; [and] in some cases brigade, although we're still working that. But what we've not been able to do, as Chris talked about, is push that down to the Soldier level, where those captains and lieutenants and sergeants have the same kind of situational awareness that was alluded to in the "60 Minutes" piece on the F-35 (http://www.cbsnews.com/news/f-35-joint-strike-fighter-60-minutes/) [spotting an enemy plane 10 times faster than it spots the F-35]. The people with the most complex military problem to solve and the least information technology behind them--those are those sergeants, lieutenants and captains at that level. And that is revolutionary. That's game-changing. I mean, not to be facetious, but if we were able to achieve the kind of virtual data wall that they show in the TV show "Intelligence," where the guy has a chip in his head, that would be revolutionary, because then you would have the ability of leaders at the lowest level to go through multiple repetitions of virtual training so that they were able to compress [Malcolm] Gladwell's 10,000 hours [the idea, based on a study by the psychologist Anders Ericsson, that mastery of a skill is often the process of spending 10,000 hours practicing] so that they had the judgment and experience to employ all the capabilities that we put at the beck and call of our special operators, even though they're 20 to 25 years old. That is revolutionary.

So, the human first. Then changing the physical plant that the Army uses so that you're able to respond and influence events at speed as we've discussed, operate in a more distributed fashion where you make exterior lines an advantage and not a challenge because you demand less logistically. And you're able to present the enemy with multiple dilemmas simultaneously. That's revolutionary.

We have been striving to conduct a nonlinear kind of distributed operations for decades, and we've done it successfully, really, in only one major operation. And that, of course, was Panama, where we took, I think it was 22 separate targets in about 14 hours. I'm talking about major facilities, government locations, units, etc. Being able to do that on a routine and recurring basis in the future will have a fundamental impact on how we operate--and, quite frankly, how we're able to deter conflict, control it, manage it and further our interests. So that's revolutionary, and that's where change in the materiel piece that Chris Cross talked about is so important. So those three things right there are all revolutions that have great opportunity.

Army AL&T: You mentioned Unified Quest. How does ARCIC keep up with the competition, keep track and ahead of our adversaries' capabilities? Do you have a red team that does that sort of thing?

Maj. Gen. Hix: Yes, our TRADOC G-2 [which develops, delivers and validates the operational environment products and services to enable realistic training, leader development, education, concepts and capabilities] is responsible for projecting the future operational environment, and [for] looking at strategic and operational and tactical trends in conjunction with a lot of other elements or intelligence agencies, down to the very science that's being explored and invested in across the globe. So we're not focused solely on the current adversaries; we're looking at technological and systems developments worldwide, because one of the key trends, of course, is that access to technology and knowledge is becoming more and more diffuse.

Being able to corner the market in a particular area is increasingly difficult. So, [we are] starting with them and then leveraging the war games, studies, seminars, working with academia and, quite frankly, working with our allies and partners across the globe. We have 17 or 18 representatives here at TRADOC from other partner and allied nations that help us see things through a different light and help us stay connected.

The other piece is that we stay very connected to the science and technology arenas, including working with the White House Science Office--again, basic research, the labs at various universities, both those that are hosted by or sponsored by the U.S. government and those that aren't, and then the [U.S.] Department of Energy and others. We've got a wide net, and one of the mechanisms for bringing that thinking together is the Unified Quest effort. But we are not limited by that.

Army AL&T: How do you make sure that tomorrow's solutions aren't obsolete by the day after tomorrow?

Maj. Gen. Hix: The first thing we do is we stay tight with our science and technology partners both in and out of the government. The first piece is to understand what the art of the possible is and where things are going. Conversely, through the survey processes and war-gaming, we also develop concepts where we think we're driving technology. And those two things are complementary. They're not exclusive efforts.

And then you've got a balance, and this is where the iterative exchange of information and discussion throughout the process [come in]. You don't want to source-select too soon because you could wind up putting yourself in a bind. Neither do you want to do it too late. If we had bought Renault tanks, which we were using for experimentation in the 1920s, we would have been woefully out of position come World War II. We did it too soon with the Future Combat System [FCS], in part because of the processes that we are currently required to operate inside of. We were co-developing a system and the S&T [that would operate it] at the same time. And, frankly, we just couldn't

get that done.

Somebody the other day called it the Goldilocks principle: Not too soon, not too late, just right. But there's an art to it as well, I guess, is the short answer. And that requires cooperation and collaboration.

Army AL&T: Can you give us an example of the most exciting or promising concept that you've developed in the past decade?

Maj. Gen. Hix: I would start with the '90s. I was here at TRADOC as a field-grade officer and had an opportunity to be involved in three major efforts. The first one was Force 21. The second one was the Stryker brigade. And the third one was the Objective Force, of which the centerpiece system was FCS.

Of those three, I saw Stryker fielded, taking the ideas of Army After Next and then trying to bend them to a current capability. So we built an organization that was enabled by information, ?infantry-heavy, very mobile, and for the first time we actually integrated UAVs [unmanned aerial vehicles] in a tactical formation. And that unit has performed, I think, magnificently both in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The 4th Infantry Division is the initial manifestation of Force 21. And while we're still working on getting a Common Operating Environment, getting our networks fully put together, we have fielded units capability sets that they've taken to Afghanistan and used with great success over there.

And then the last one, the Objective Force, may have been too soon in terms of its implementation, and we may have been too aggressive on our timelines. We pushed the technology before it was mature enough. Again, that's why you've got to be looking out 30 years--because you've got to be working on it today if you want to see it physically fielded, say, 20 or 30 years in the future.

Army AL&T: Although the 30-year modernization planning process is relatively new, is there any promising thing that you're seeing right now?

Maj. Gen. Hix: Human Dimension, started in the mid-2000s, which is about optimizing and enhancing our human performance--that's a very promising idea, and we think there's going to be a lot of impact on that both for Force 2025 and beyond. And then the other one, as Gen. [Robert W.] Cone [then-commanding general of TRADOC] mentioned down at AUSA in Huntsville, the Expeditionary Maneuver Concept recognized the future--increasingly connected people, the momentum of a given interaction, greater urbanization, population growth, etc. Speed-of-event effect is going to be a huge driver of our thinking over the next 10 to 20 years.

In terms of the 30-year plan, two points are very important here, and I'll let Chris touch on these as well. The first thing, looking out 30 years, is now allowing our RDECs [research, development and engineering centers] to extend their investment programs beyond what has been recently a five-year transition window. So they're actually looking out and finding places where they can be more innovative because they've got more time to develop technology, and the program managers and PEOs are expecting tech inserts at various points in programs' development as well as points of obsolescence--when we're going to end a program of record or bring a new one on board. So having that long view is very important in that regard.

And because of the time horizons of the Unified Quest team and our overmatch analysis within the intelligence community, it allows us to align where we see science and technology, particularly from an adversary standpoint, against our system so that we're not caught by surprise by the next big thing being in somebody else's possession instead of ours.

Col. Cross: One of the challenges we face in DOD science and technology is [that] oftentimes, as Maj. Gen. Hix said, our programs are too short-lived. If your success is measured by how quickly you're able to choose in five years, it doesn't encourage risk. In fact, what it encourages the science manager to do is take a less risky path that will continue to be rewarded with funding. If I extend the program out to 10 or 15 years and I can develop alternate, diverging paths, one that's less risky but one that's willing to accept risk and is willing to tolerate risk, that's where we'll get the great breakthroughs.

We met Mr. [Frank] Kendall [undersecretary of defense for acquisition, technology and logistics] the other day, and one of the things he is now saying is that if the DOD lads don't begin to accept some risk and become more innovative and creative, there will be a potential for money to be shifted to organizations [such as] DARPA [the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency]. We have been risk-averse in our programming over the last years in terms of the S&T. In many cases, we have measured success of our S&T programs in transitions to programs of record. If there's success in S&T investments to programs of record, then you're not going to get the innovative and creative ideas that are necessary to fundamentally change the Army and develop the game-changing capabilities that must be developed if we're going to be a lighter, more lethal and agile force moving into the decade of the '30s.

Just to amplify what Maj. Gen. Hix said, one of the really interesting things I see with the modernization strategy is that it allows me to look at where we think the Army is going to go today, overlay that with the emerging threat capability and do an analysis as to whether we're making the right decisions with the S&T investment strategy. It may be that the capability we're developing won't allow it to prevent overmatch, and so that's really an important aspect of this 30-year modernization strategy from our perspective.

Army AL&T: What do you see as your greatest challenges to ARCIC's success with your process?

Maj. Gen. Hix: From a process standpoint--and this is not ARCIC, this is an Army and DOD challenge--it's the issue of continuity, having the ideas, focus and priorities be consistent over a number of years. I mentioned the AirLand Battle piece--our first commander or second commander at TRADOC noted it took him eight years to get AirLand Battle into doctrine. It took us 18 years to develop--with a failure in the middle, I might add, the M1 tank. It started out as a main battle tank for 1970, and it failed, but then they built one on top of that with the lessons learned from that. But it took us 18 years.

The thing that drove that was a common view of the problem and a common understanding of what had to be done and what the priorities were. So while each commander of TRADOC and other leaders within the Army added things to the pot of soup, if you will, they were all focused on how we recover the Army from Vietnam, maximize its combat potential, take apart the echelon system of the Soviet Army, etc., at the same time being agile enough to deal with other challenges. I would note that the Army that was so dramatic in fighting a tank battle in the desert in Desert Storm was also the one, as I mentioned, that just a year earlier knocked out Panama in about three weeks total--three or four weeks from start to finish, but the battle was over within the first couple of days.

So that Army was not by accident. That Army was by design. And it demanded the focus of five or six chiefs [of staff of the Army] and as many TRADOC commanders and FORSCOM [U.S. Army Forces Command] commanders and AMC [U.S. Army Materiel Command] commanders to get there. And so that's going to be one of our challenges going forward, that process. And it's true of other services and capabilities as well. You look at stealth and the single-minded focus of the DOD--not just the Air Force, but the DOD--to achieve stealth capabilities in the military. Cruise missiles is another great example of that. Nuclear submarines--single-minded focus, long-term view and consistent investment in priorities over a very long time. And in the case of stealth and the nuclear submarine, I would note, they still have those same priorities. The last thing I would say is that the department has yet to prioritize ground force capability in the way that they have uniformly prioritized things like nuclear submarines, stealth and cruise missiles from the beginning.

For more information on ARCIC, go to http://www.arcic.army.mil.

Related Links:

U.S. Army Acquisition Support Center

Social Sharing