Listen my children and you shall hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere,

On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-five;

Hardly a man is now alive

Who remembers that famous day and year.

These words were penned on the eve of the American Civil War by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in his poetic retelling of Paul Revere's "famous" ride. Since then, generations of Americans have considered Paul Revere an icon of Revolutionary War history. However, Paul Revere was not the only rider, (there were two others), and he did not make it all the way to his destination of Concord, but was captured and then let go (without his horse) in Lexington. Longfellow greatly exaggerated Paul Revere's role in this incident. According to the Maine Historical Society's website, the poem "rescued a minor figure of the Revolutionary War from obscurity and made him into a national hero." Why, then, did the Home of Military Intelligence memorialize a barracks after Paul Revere? Who was this man? What did he do for Intelligence?

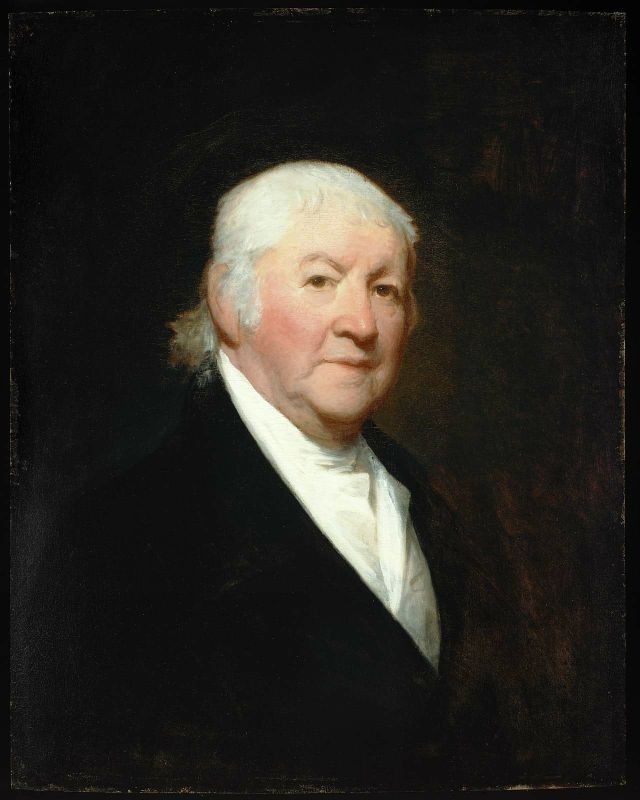

Paul Revere was a silversmith from Boston. He was also a devoted patriot, participating in the Boston Tea Party, and a devoted family man. He had eight children with his first wife and, after her death, eight with his second. He lived an ordinary life in extraordinary times. It is likely that had Longfellow not written this poem 85 years after the fact, Paul Revere might never have been mentioned again in the annals of history.

One, if by land, and two, if by sea;

And I on the opposite shore will be,

Ready to ride and spread the alarm

Through every Middlesex village and farm,

For the country folk to be up and to arm.

On the night in question, (April 18, 1775), Paul Revere was given the task of warning Patriot leaders John Hancock and Sam Adams, who were in Lexington, that they were probable targets of a British operation. He did arrange to have warning lanterns hung in the Old North Church to alert other Patriot forces across the river as to the means and route of the British advance. Contrary to Longfellow's version of the story, Revere was not the one receiving the signals, but the one sending them. One could make the argument that Paul Revere was utilizing an early form of code signaling, but that would be a stretch -- hardly deserving of memorializing a building on Fort Huachuca. There must have been more to Paul Revere than this.

In fact, Revere was a member of a group called the Mechanics. According to the Central Intelligence Agency, it was the first Patriot intelligence network on record. He and other members of this secret organization were actively conducting surveillance, signaling warnings, and collecting intelligence ten full years before the outbreak of the Revolution in April 1775.

The Mechanics were a group of skilled laborers and artisans who had originally organized themselves as the Sons of Liberty opposing the Stamp Act. In 1765, the British Parliament imposed this tax on every piece of printed paper used by the colonists. This meant that ship's papers, legal documents, licenses, newspapers, even playing cards were to be taxed in order to raise money for the Crown's frontier ventures. Many colonists felt that they should only be taxed by their own colonial legislatures -- hence the slogan, "No taxation without representation." The Sons of Liberty effectively repealed the Stamp Act the following year, and the group disbanded. Energized and encouraged by their success however, many of the activists, known also as the Liberty Boys, continued to organize resistance to British authority. Eventually, their efforts began to look more like a covert intelligence operation.

Paul Revere was one of these men. The Mechanics would take turns patrolling the streets at night, watching British soldiers and gathering information on their movements and activities. In addition to their surveillance activities, they often sabotaged and stole British military equipment in the Boston area. Unfortunately, their lack of training was apparent: predictably, they gathered for meetings at the Green Dragon Tavern on a regular basis and they naively selected Dr. Benjamin Church, a British agent, as one of their leaders. However, they uncovered the plot the British had devised to march on Concord and seize the weapons and munitions the Patriots had stored there.

So through the night rode Paul Revere;

And so through the night went his cry of alarm

To every Middlesex village and farm, __

A cry of defiance and not of fear,

A voice in the darkness, a knock at the door

And a word that shall echo forevermore!

The morning after this ride, a skirmish ensued between a British column and about 70 American "minutemen." The British troops continued along the road to Concord, expecting to find caches of munitions and arms -- but they had been removed by the alerted patriots. On their way back to Boston, the British force came under sustained attack from over 4,000 minutemen, suffering 73 dead and 174 wounded. There is no question that the actions of Paul Revere and his comrades on the night before this "shot heard round the world" facilitated the Patriots' initial success.

Poet and author Dana Gioia, in an essay on Longfellow's work, wrote, "the galloping Revere acquires an overtly symbolic quality. He is no longer the historical figure awakening the Middlesex villages and farms. He has become a timeless emblem of American courage and independence." Longfellow apparently never intended to write a history, according to the Maine Historical Society. He did intend to create a national hero during a time of great national upheaval and division, and in that he was successful. But let us not overlook that Paul Revere was more than a national myth; he was a real person with a selfless mission who took great risk to act on it. He provided good intelligence at a crucial moment, and the rest was history.

Social Sharing