As an instructor for the Command and General Staff Officer Course, I often observe Army officers understandably defaulting to their experience when first learning about or performing sustainment planning during joint practical exercises. Many times, not unexpectedly, they start planning almost solely from an Army perspective, specifying detailed tasks to Army sustainment units by field service and class of supply. I propose a simple construct for them to use when thinking about planning joint sustainment.

The planning construct is quite straightforward: three rules should be followed in sequence. First, sustainment is provided by the service (Army, Air Force, Navy, or Marine Corps) or the Defense Logistics Agency (DLA), which responds to the services. Services plan what they are responsible for: sustaining themselves.

Second, the joint planner must consider exceptions to the first rule (service sustainment) if those exceptions make sense for the operational context at hand. The third rule is that items not covered or that are in conflict with the first and second rules will be reconciled using primarily joint boards, centers, offices, cells, and groups.

By applying this rather simple construct to the specific operation being planned, planners can think around the complex limitations that the law, policy, and doctrine relating to service and joint sustainment impose.

RULE 1

The first rule--that sustainment is provided by the service or DLA--is derived from the service responsibilities listed in Title 10 of the U.S. Code and supplemented by directives from the Department of Defense. Based on these laws and directives, all of the services have major commands to support their requirements, including the Army Materiel Command, Air Force Materiel Command, Navy Supply Systems Command, and Marine Corps Logistics Command. They also have service-unique force structures to support operational- and tactical-level sustainment operations.

The above phrase, "or the Defense Logistics Agency, which responds to the services," is important because the Secretary of Defense may designate a single agency to "provide for the performance of a supply or service activity that is common to more than one military department" when he "determines such action would be more effective, economical, or efficient" (Title 10, chapter 8).

According to its website, DLA is responsible for sourcing and providing "nearly 100 percent of the consumable items America's military forces need to operate." So, with the statutory requirement for the services to support themselves and DLA functioning as an important part of the system, the structure and responsibilities are in place for sustaining joint operations.

Since a service is responsible for providing sustainment support to its forces, the Army service component planners in the joint force are responsible for planning the Army's support in detail. Joint-level planners do not need to specify detailed tasks to Army sustainment units.

Much of the sustainment planning will be done by the services in support of their own requirements. Some sustainment responsibilities will always remain with the service because of their uniqueness (for example, the maintenance of the Air Force's fighter aircraft or the Army's Bradley fighting vehicles).

Included in the first rule of joint logistics planning (that sustainment is provided by the service) is the need to consider sustainment functions assigned through executive agent directives or other instructions to a single service or agency. These sustainment functions include DLA's responsibilities as the executive agent for subsistence, bulk fuel, construction and barrier materials, medical materiel, and other consumables.

Another example is the Army's designation as the executive agent for functions such as the management of overland petroleum support, land-based water resources, the Defense mortuary affairs program, and veterinary services. These responsibilities allow for the identification of and the planning for sustainment functions that have been officially tasked to a service or agency and that must be provided to all forces employed in the joint operation.

The executive agent role is new to some students, however, and thinking through this part of the planning construct prompts them to research and find out what support a service or agency needs to plan--not only for itself but also for the other joint forces involved in the operation. Some assumption-based planning is usually required since the capabilities and requirements of other services involved in the operation are not always clear. (The Department of Defense executive agent list can be found at http://dod-executiveagent.osd.mil/agentlist.aspx.)

RULE 2

The second rule of the construct, "consider exceptions to the first rule if they make sense," is deceptively simple, but it is meant to cause the planner to consider exceptions for the specific joint operation being planned. This is the most important area on which the joint sustainment planner should focus.

The planner must consider the type of operation, its location, the forces involved, and the deployment sequence and then consider the sustainment functions that could or should be provided by a single service or between services. A service may be designated as the lead because that service is the dominant user of sustainment commodities, or because it has the greatest capability to provide the support, or to create efficiency.

Designating a single service as the lead for a sustainment function reduces the overhead created when all services must bring their own capabilities to provide sustainment commonly used by others. Some examples are feeding, retail fuel support, billeting, contracting, maintenance of common vehicles, and medical support. These exceptions to service-only sustainment are not only more efficient; they also potentially allow for a more effective operation by freeing up scarce strategic transportation assets for forces necessary for the decisive phase of the operation.

This rule in joint planning can be the most challenging because each situation is unique and force lists, sequencing, host-nation capabilities, and priorities vary depending on the operational context. However, this rule is the most important for the joint planner because it identifies what the services need to know to sustain the operation being planned.

Services generally have the first rule figured out (they are responsible for supporting themselves) but they need to know what else they are expected to do if the joint force commander identifies additional requirements. Rule 2 lets the service component sustainment planner know what to plan for that is not routine.

For example, while a service must plan support to feed members of its service, it needs to know if it is also feeding another service during the operation. It needs to know if it will be providing medical or base support to members of other services.

Knowing these details allows the service component planners to plan in order to ensure enough capability and capacity are available to provide such support, and it can assist them in setting up the coordination and reporting mechanisms to facilitate that support.

To decide if a lead service is appropriate, the joint planner considers how to make the operation more efficient and effective rather than just defaulting to the statutory requirements and letting all the services bring what they need to provide their own support. Considering who the dominant user is or who has the most reasonable capability to support other forces, as well as other considerations--such as what is reasonably available in theater from the host nation--allows decisions to be made regarding joint support for this particular operation.

Depending on the maturity of the planning for an operation, some services may have already been designated as a lead service in a plan. At times, services may have coordinated and put in place interservice support agreements (ISSAs), which means they have worked out their requirements between them without being directed to do so by a higher level joint order.

Joint Publication (JP) 4-07, Joint Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures for Common-User Logistics During Joint Operations, lists Army logistics support to U.S. Air Force tactical air control parties (USAF TACPs) as an example of an ISSA. The JP states that "this particular Service Secretariat-level ISSA is a long-term agreement that requires the Army to provide significant common-user logistic support--life support, fuel, selected maintenance, [and] Class IX [repair parts] support to USAF TACPs that are attached to Army tactical units."

Again, by focusing on this second area of the planning construct, the joint planner will think through and potentially task requirements that are not part of the routine for services in an effort to make the operation as efficient and effective as possible. However, the joint planner will not think of everything, and inevitably friction will occur between the services requiring additional decisions and prioritization, which leads to the third rule of the planning construct.

RULE 3

The third rule of this planning construct is that items not covered or that are in conflict with Rules 1 and 2 are reconciled before and during the operation using joint boards, centers, offices, cells, and groups. Sustainment challenges or conflicts that were not fully anticipated in the planning process will always emerge during the operation.

Doctrine provides for the establishment of a number of boards, centers, offices, cells, and groups. These bodies are designed to serve primarily as coordinating authorities, and they make or recommend decisions to rectify problem areas or reduce the friction that occurs when multiple services are operating in the same area, often competing for the same space and resources.

These bodies have slightly different functions depending on whether the action requires a decision or if it is an enduring requirement. Additionally, they may be formed at different headquarters--some at the geographic command level and others at the subordinate joint force headquarters.

According to JP 1-02, Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, a board is "an organized group of individuals within a joint force commander's headquarters, appointed by the commander (or other authority) that meets with the purpose of gaining guidance or decision." Sustainment-related examples are the joint acquisition requirements (or review) board, the joint facilities utilization board, and the logistics procurement support board.

A center is "an enduring functional organization, with a supporting staff, designed to perform a joint function within a joint force commander's headquarters" (JP 1-02). Sustainment examples are the joint deployment and distribution operations center, the joint logistics operation center, joint movement center, and the joint patient movement requirements center.

An office is "an enduring organization that is formed around a specific function within a joint force commander's headquarters to coordinate and manage support requirements" (JP 1-02). The joint blood program office, joint medical regulating office, joint mortuary affairs office, and joint area petroleum office are examples of sustainment offices.

A cell is "a subordinate organization formed around a specific process, capability, or activity within a designated larger organization of a joint force commander's headquarters" (JP 1-02). Examples are a host-nation support coordination cell, a deployment cell, a joint transportation coordination cell, a medical coordination cell, a theater distribution management cell, and an engineer coordination cell.

A group is "a long-standing functional organization that is formed to support a broad function within a joint force commander's headquarters" (JP 1-02). While specific sustainment-related "groups" are not often established, the joint sustainment planner can influence future operations by participating in joint planning groups, which can be especially important early in the operation when force sequencing decisions are being made.

As a means to resolve problems that will inevitably occur, the joint planner can start setting up or coordinating with boards, centers, offices, cells, and groups early in the planning process. A savvy planner will start developing the battle rhythm of these organizations to facilitate timely decisions and to provide the venue for problem resolution.

APPLYING THE RULES

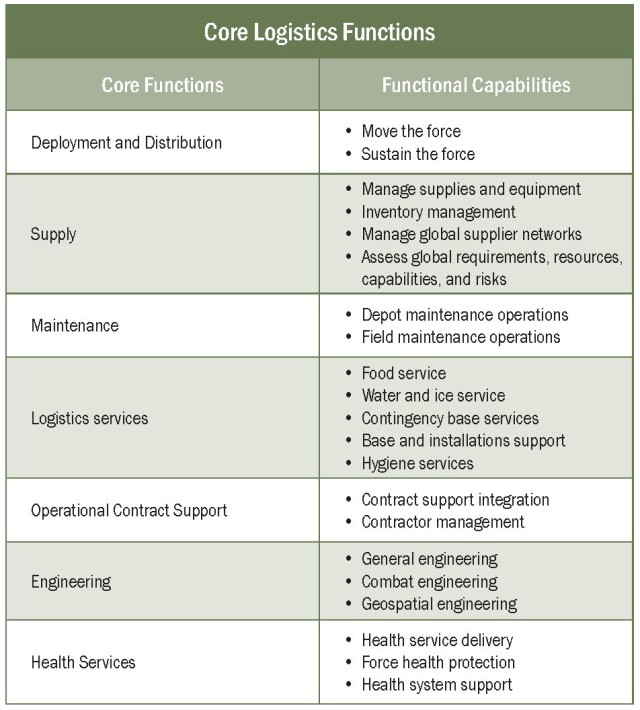

This scenario may help illustrate the construct described above. Imagine being on a joint staff executing crisis action planning to establish an expeditionary forward operating base from which Army, Air Force, and Naval aircraft will operate in support of a small-scale contingency operation that may also involve humanitarian operations. Looking at a list of core logistics functions (figure 1) from JP 4-0, Joint Logistics, may help in this discussion.

Considering Rule 1, each service should plan to deploy the sustainment capabilities needed to support itself. Army, Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps component planners will consider their own force's deployment and determine when and where the supplies, maintenance to support deployed equipment, health service support, and life support for their personnel are required.

If designated as an executive agent, component planners also must consider the capabilities required to support other services. For example, the Army is the executive agent for mortuary affairs and veterinary support, so it needs to plan to bring resources in those areas for all service forces deploying. As the executive agent responsible for providing bulk petroleum, barrier materials, subsistence, and medical materiel to all the services, DLA is an important partner in the service component planning process.

Applying Rule 2, the joint sustainment planner considers exceptions to Rule 1 and plans to eliminate redundancies where it makes sense for the operation. Assuming that the Air Force is the predominant service for this operation, perhaps it makes sense for the Air Force to provide subsistence and base support for all participating elements.

For efficiency's sake, the Army could deploy the resources to provide medical support to all the services and to repair ground vehicles common to all the services. Naval forces might be tasked to provide the construction engineering capability for the task force; this is a requirement all the services will likely have, and all services have engineering capability in their force structure, but tasking it to a single service may reduce redundancy and clarify responsibilities.

The above are simple examples, but the process illustrates where the joint planner's analysis should be focused--not on the service requirements, but on the requirement to make this operation as efficient and effective as possible by reducing unnecessary redundancies.

Understanding that there will be evolving and unanticipated challenges, the planner can apply Rule 3 and start considering the structure of and coordination authorities for the appropriate board, center, office, cell, and group and how these bodies fit it in the task force's battle rhythm.

This framework should help a planner think through the joint planning process. It considers a service's Title 10 responsibility to sustain its own forces, accounts for the combatant commander's plan for service leads in certain areas when it makes sense for efficiency or effectiveness, and takes into consideration that unanticipated requirements and conflicts will arise and will need to be addressed through a board, center, office, cell, or group.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Mark Solseth is an instructor for the Command and General Staff Officers Course at Fort Lee, Va. He has a bachelor's degree in economics from Colorado State University and master's degree in military art and science from the Command and General Staff College (Advanced Operational Art Studies Fellowship). He is a graduate of the Joint Professional Military Education Phase II and the Command and General Staff Officers Course. _____________________________________________________________________________________________________

This article was published in the March-April 2014 issue of Army Sustainment magazine.

Related Links:

The Department of Defense Executive Agent List

Army Sustainment Magazine Archives

Social Sharing