Native Americans had been utilized as Scouts as far back as white men had been settling the American continent. After the Civil War, Indians from more than a dozen tribes were enlisted to assist the Army during the Indian Campaigns of the Great Plains and Southwest regions. By 1866, the Army had been engaged in the Indian Wars for twenty years. The borderlands, however, posed particular challenges. With limited manpower, the Army, needed help because of the sheer size and difficulty of the land area involved. Congress, therefore, authorized the Army to form a corps of up to 1,000 Indian Scouts for reconnaissance and combat duty on August 1, 1866. In 1871, as Commander of the Arizona Territory, General George Crook was charged with subduing the last of the warring tribes and finally bringing order to the frontier. Facing desolate, unmapped terrain, brutal conditions, and a desperate enemy, Crook recruited White Mountain and San Carlos Apaches to chase down the elusive Chiricahua Apaches, led by Cochise. Crook was so impressed with the Scouts' service that he recommended them for Medals of Honor from the US Congress, which they received in 1875. On their behalf Crook wrote: "Without reserve or qualification of any nature…I assert that these scouts did excellent service, and were of more value in hunting down and compelling the surrender of the renegades than all other troops engaged in operations against them combined." Once relative peace had been established, Crook was reassigned.

A new outpost was needed close to the US/Mexican border, one that would serve as a base of operations: Camp Huachuca was established in 1877 for just that purpose. However, the Indian Wars dragged on for another ten years. General Crook was called back to Arizona and he did not hesitate to call on his Scouts again. His extensive use of and trust in Indian Scouts, and his willingness to negotiate rather than use force, made Crook unusual among Army generals. For their part, the Scouts had first-hand knowledge of "every trail, every water hole, every hideout in the vast labyrinth of mountains crisscrossing the southwest." The "enemy" was not only their own tribe, but often their own clan. Crook believed there was none better to track the Apache than other Apache. The Apache Scouts played a decisive role, right up to the final surrender of Geronimo in 1886. Sadly, in the end, the US Army Scouts were treated the same as the conquered prisoners of war, and shipped far from their beloved Arizona to Florida for incarceration. Crook would spend the rest of his life campaigning on his former enemy's behalf, speaking out against white encroachments on Indian lands and working for the Apaches' return to their homeland.

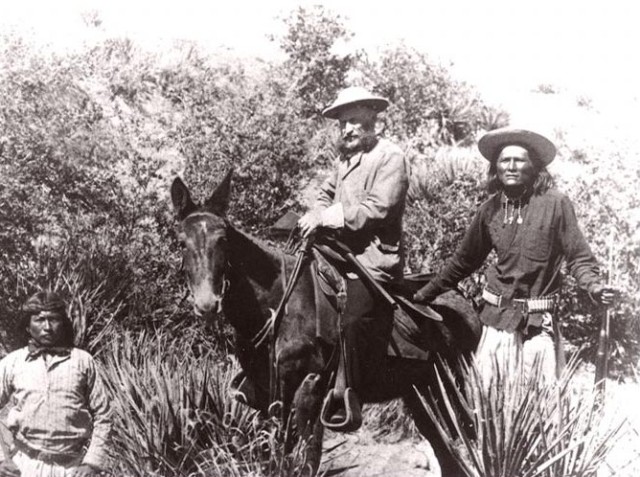

Sergeant William Alchesay

Probably the most famous of Crook's Apache Scouts, Sergeant William Alchesay, or the "Little One," was born between Globe and Show Low, Arizona in 1853. He enlisted in 1872 at Camp Verde, Arizona, and became a Sergeant in A Company, Indian Scouts, commanded by Lieutenant Charles B. Gatewood, 6th US Cavalry. Sergeant Alchesay was one of ten Apache Scouts who guided Crook's columns during the winter campaign of 1872-1873 against the Chiricahua Apache. The Medal of Honor citations for all ten Scouts cited, "for gallant conduct during the campaigns and engagements with Apaches."

In March 1886, Sergeant Alchesay was called upon again to assist General Crook in the Geronimo Campaign. Alchesay was present at Geronimo's surrender on March 27th at Canyon de los Embudos in Sonora. The old warrior asked Alchesay to speak on his behalf. Speaking as both Scout and Apache, Alchesay said, "They have all surrendered. There is nothing more to be done… I don't want you have any bad feelings about the Chiricahuas. I am glad they have surrendered because they are all one family with me." Geronimo would escape confinement one more time and have to surrender again to General Nelson Miles, but the trust that was bestowed on Alchesay by both his fellow Soldiers and his brother Apache spoke highly of his character.

Alchesay served more than fourteen years in the Army, eventually becoming a Chief of the White Mountain Apache Tribe until he retired in 1925. He made numerous trips to Washington D.C., visiting with President Grover Cleveland and acting as a counselor to Indian Agents in Arizona Territory. Chief Alchesay died in 1928, a chief to his own people and a hero to the US Army which depended so much on his abilities. He was inducted into the MI Hall of Fame in 2012 and his proud descendants traveled to Fort Huachuca to dedicate a new plaque on Alchesay Barracks, named for him in 1975.

Staff Sergeant Sinew Riley

After Geronimo's final surrender, the Indian Wars were effectively over. There was little need for the Apache scouts so their numbers were reduced dramatically. In 1922, all remaining Apache Scouts were transferred to Fort Huachuca. The ranks thinned quickly after that, since discharged and retired scouts were not replaced. By 1924, only eight Scouts remained. All but three had enlisted after 1920, long after the Indian Wars ended. While there wasn't much official work for them to do, they participated on regimental maneuvers, relaying messages and doing leg-work around the headquarters.

In 1933, the Army built adobe huts for the Scouts and their families in an area that became known as "Apache Flats," and installed plumbing, stoves, and shower facilities, but the Indians rarely used them, preferring to camp in their wickiups near the post cemetery. In 1947, the War Department ordered the retirement of the last four Scouts; one was Sgt. Sinew L. Riley. In his book, Fort Huachuca: Story of a Frontier Post, historian Cornelius Smith recorded Sgt. Riley's moving words:

We were recruited from the warriors of many famous nations. We are the last of the Army's Indian scouts. In a few years we shall be gone to join our comrades in the great hunting grounds beyond the sunset, for our need here is no more. There we shall always remain very proud of our Indian people and of the United States Army, for we were truly the first Americans and you in the Army are now our warriors. To you who will keep the Army's campfires bright, we extend our hands, and to you we will our fighting hearts.

Social Sharing