RAMSTEIN, Germany (July 10, 2013) -- One of the U.S. military's biggest accomplishments in post-war Europe was unintentional: the music the GIs listened to on the radio made a deep, positive impact on Europeans that continues today.

Prior to AFN's arrival, Nazi Germany had banned most American music, as "decadent," and even after the Americans first arrived, state-run German radio didn't play English language music. When rebuilding began after World War II, American Soldiers seldom mixed with locals. Regulations prohibited it and few spoke the local language.

But some curious Europeans chose to invite the GIs' radio station into their home, car or restaurant: the American Forces Network Europe, known throughout the world as AFN. Many Europeans wanted to hear the rich diversity of jazz, blues, country and rock music that wasn't airing on their country's radio stations.

AFN never intended or tried to broadcast to host nationals. As a matter of fact, the network took extraordinary measures to not reach them.

AFN's linked radio transmitters used special broadcast patterns targeted where the Americans were stationed, the music and the talk was all in English and most transmitters were low-powered, so planners didn't think many people living in Germany, Italy, France, Austria or Belgium would bother tuning in.

But they did.

Historian Dr. John Provan said a survey in AFN's early years indicated the military network was reaching a potential listening audience of 50 million Europeans.

AFN began broadcasting from locations in France, Austria, Italy, Germany and Belgium, and was heard, despite restrictions, in Paris, Vienna, Frankfurt, Berlin, Munich and other major population centers. While many transmitters were low-powered, some were "sound monsters," with the Munich and Weisskirchen, Germany, AM transmitters reaching much of Europe.

At night, the Weisskirchen signal skipped across the English Channel into the United Kingdom. AFN first broadcast from BBC studios in London on July 4, 1943, but American broadcasts in the island nation ended after the war.

Ironically, a generation of English-speaking kids was among those trying hardest to pick up the faint American radio signal because in the 1950s, Brits weren't hearing jazz, blues and rock on their local radio stations.

One of the lads listening in was Led Zeppelin front man Robert Plant. He talked to David Letterman about why he chose the crackly distant AFN signal over local radio stations in the United Kingdom.

"We didn't have the same cultural exchange you had. We didn't have Black America," he said. "We couldn't turn our dial and get an absolutely amazing kaleidoscope of music. (In the UK) now and then, if you were lucky, there was this American Forces Network radio coming out of Germany. If you were lucky, you could hear Muddy Waters or Little Richard coming through the waves."

Plant and Zeppelin's lead guitarist, Jimmy Page, both say American blues and jazz heavily influenced their music. They got that exposure by listening to the American military's radio network in the 1950s.

"To hear current releases, you tuned in AFN and hoped that you could catch the title of something after they played it," Page said in an interview with Rolling Stone Magazine.

At the same time another future musician, Van Morrison, was struggling to tune in AFN as a boy growing up in Northern Ireland.

The singer of rock classics "Brown Eyed Girl" and "Moon Dance" even wrote a song about trying to listen to AFN back then called "In the Days Before Rock and Roll."

The impact of AFN on Bill Wyman, the bass player for the Rolling Stones for 31 years, was even stronger. He was a British soldier stationed in Germany listening to AFN Munich at night.

According to the German audio magazine "Schau ins Land," Wyman said he was so fascinated with what he was hearing that he went out and bought a guitar to play, and that without AFN Munich he would not have become a musician and certainly would not have been with the Rolling Stones.

AFN played a major role in introducing American country music to the Europe.

In Germany, clubs featuring line dancing, Western garb and country music popped up in the '70s and '80s, such as the huge club "Nashville" near Nuremberg.

Germans started forming bands such as Truck Stop, with country songs in German. In one tune, they sang about wanting to listen to Dave Dudley, Charlie Pride and Hank Snow but AFN was too far away. German radio stations started their own country music DJ shows.

German radio and TV personality Fritz Egner said the Munich-based producers of Donna Summer's disco classics listened to AFN for inspiration. Another Munich based group, Silver Convention ("Fly Robin Fly") used an AFN newscaster for one of their tracks.

Egner said an early '60s German newspaper survey indicated more than twice as many Germans were listening to AFN than Americans.

"AFN was probably the best ambassador for the U.S. in the post-war era," said Egner. "It was sort of like a radio station from another planet. They played the music we didn't hear and presented it in a different kind of way."

Egner got his broadcasting start with AFN, where he was known as AFN Munich's tap dancing engineer. His side-kick role on AFN led to a German radio station hiring him as a DJ. He then went on to host several popular German TV programs, including a version of Candid Camera.

Around Europe, other stations were looking for AFN DJs to bring their "crazy" American style of show to their airwaves.

In Belgium, one of the biggest classic rock DJs on the air today started with AFN SHAPE, Patrick Bauwens. Radio Luxembourg hired former AFN Soldier Benny Brown and he's still playing the hits.

AFN Berlin's Air Force Sgt. Rik De Lisle left the military to become a radio DJ and program director for German radio. AFN Nuremberg's Mike Haas, left the Army to become the founding program director of radio station Antenne Bayern in 1988 and still works in Germany as a media consultant.

AFN music served as a bridge with the United States and a generation of future politicians.

Germany's foreign minister and vice chancellor from 1998-2003, the Green Party's Joschka Fischer, said the music he listened to on AFN heavily influenced him.

According to the book "Joschka Fischer and the Making of the Berlin Republic," when asked who had a more profound influence on him, Bob Dylan or Karl Marx, Fischer snapped, "Clearly Bob Dylan. His music has always been a highly emotional thing for me; I wanted to be free."

Other Green Party officials felt a similar bond with AFN.

When the American military was about to leave Berlin and Frankfurt, Green Party leaders asked if AFN could stay, not realizing that the network was as much a part of the American military as the infantry.

A politician from another German party, the CDU's former state of Hessen Minister Roland Koch, said he learned to speak English by listening to AFN. He, like a generation of Germans now in their 40s-through-60s, started to listen for the music, then got interested in learning English to understand the lyrics.

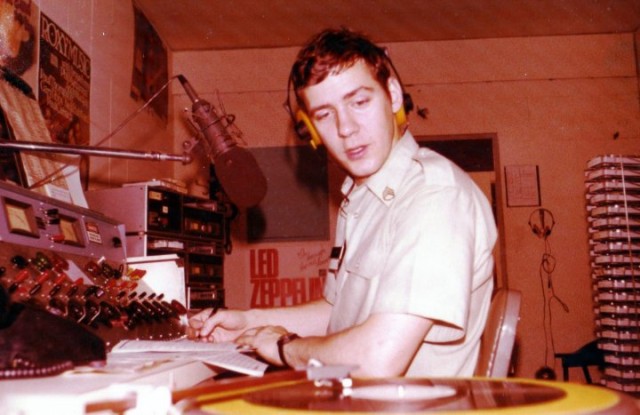

It was during my two years as an Army staff sergeant DJ in AFN Nuremberg, from 1979 to (19)81, that I personally came to understand the depth of the impact AFN had made on its "shadow audience" of non-American listeners.

Both happened when I was doing the morning show with the air name, "Gorgeous George."

While that moniker could have gotten me sued for truth in advertising, it was a lot more memorable than my real name, George Smith. At least one host national agreed with me.

One night I went to the biggest disco in town and was shocked to hear him open his microphone, call himself AFN's Gorgeous George and proceed to use some of my favorite corny lines from my shows. Color me shocked but flattered.

An ever bigger surprise came later that year when the buzzer to our station rang and an American wearing civilian clothes walked in with a younger man shadowing him.

It turned out the younger man listened to my show in then-communist Czechoslovakia, escaped across the border and now wanted to meet me.

I asked him why he listened to AFN and he replied in hesitant English, "We get Voice of America in our village, but we like listening to you. You are a Soldier talking to other Soldiers -- you're going to tell them the truth."

While AFN still has loyal European listeners, there are fewer of them, because now many European radio stations sound like U.S. stations.

In Germany, some stations play almost all English-language music. Stations even have names like Big FM, Planet Radio or You FM.

Sometimes the only hint you'll get that you're listening to a German station is when you hear a song with a chorus of non-bleeped out profanity that could turn the baby's formula to cheddar or melt the FCC's complaint line. English language bad words don't count as bad words on German radio.

The fact that Europeans sought out our music and folded it into their culture is something every American can take pride in. Europeans value our diverse music. Our nation didn't try to sell them or influence them to listen. They chose to.

So without trying, American service members' music made a major positive impact on European culture and their AFN radio network forged a lasting bond with the European people.

Social Sharing