HOHENFELS, Germany -- The story sounds like a Hollywood blockbuster. British officers escaping from a World War II prison camp make their way through Nazi Germany with forged documents, carrying out reconnaissance in Berlin before being captured again mere yards from freedom at the Swiss border where they are threatened with execution as spies.

But it's not a movie. It's the true story of Sgt. Frederick Foster, one he never told, and one his son, Steve, has spent the last four years tracking down.

"It's been a journey of discovery," said Steve Foster, referencing his journey into the past which began with an old suitcase stuffed away in an attic.

"Like many retired men, you start to look at your family's past, and I decided to trace my family background," said Foster, a former Commander Engineer in the British Royal Navy.

His older sister directed to him to an old suitcase that contained many mementoes of his father's World War II days. But neither sibling was prepared for what they found.

"This amazing story shone out of a suitcase," Foster said.

Among his father's papers, Foster found a classified letter to British Military Intelligence detailing his escape from Stalag XXA in Poland, as well as letters to the family of Sgt. Foster's fellow escapee, Lance Cpl. Antony Coulthard.

"I was brought up in the loving family of a man who never mentioned the war," said Foster.

"When my sister and I read these stories, we were quite amazed."

Foster decided to trace his father's war in person on the back of a Triumph motorcycle.

"I've put 30,000 miles on that bike," he said.

His journey began in Norway, where his father was wounded and captured at the Battle of Tretten, one of the first battles of World War II.

"My father's battalion and brigade were destroyed," said Foster. "A Territorial Infantry Brigade (equivalent to U.S. National Guard) tried to hold a German Panzer division, but it didn't work."

After five days of fighting, Sgt. Foster would spend the next five years as a prisoner of war. But he did not sit idle.

"He escaped at least three times," said Foster.

Foster next traveled to Stalag XXA in Thorn, Poland, where his father spent two and a half years. During this time, Sgt. Foster spent 18 months studying German under the tutelage of Coulthard. An Oxford graduate, Coulthard spoke fluent German, and was even able to alter his accent to suit various regions.

"But my father couldn't get rid of his British accent," said Foster, "so he went as a Hungarian businessman employed with Siemens."

The pair had forged passports and a "letter of authority" from Siemens granting them permission to tour any of their factories within German occupied Europe and Switzerland, signed with the forged signature of Stalag XXA's own commandant.

Having cut through the fence with a homemade set of wire cutters, the pair boarded a train into Germany, clad in civilian clothes. For several days they traveled, narrowly escaping detection many times and making note of defensive positions such as anti-aircraft placement and camouflaged streets. They arrived in Lindau, the last German stop before Switzerland.

"At the border in Lindau, police saw there was something not quite right about (my father's) ID," Foster said. "(Coulthard) had already made it into Switzerland, but he was a good comrade, he came back to help my father who was being questioned."

The pair were interrogated extensively, beaten, and accused of being spies.

"They were accused of treason and were going to be shot out of hand," said Foster.

Finally, a phone call to Stalag XXA confirmed the identity of the two prisoners and they were returned to Poland.

"He had escaped so many times that immediately upon his return he was shipped (to Hohenfels,)" said Foster. "There was more barbed wire."

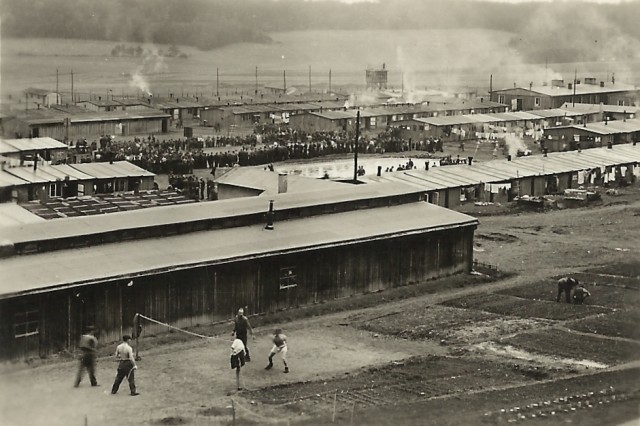

Stalag 383, in what is now the Hohenfels Training Area, served as a nonworking camp for approximately 5,000 noncommissioned officers. As a trained stenographer, Sgt. Foster worked with the camp's underground radio, taking down the news in shorthand and distributing it among the prisoners.

Foster arrived at Hohenfels June 13, his wife, Chris, perched on the back of his Triumph. Having arranged a visit to the old POW site through Norbert Wittl, U.S. Army Garrison Hohenfels public affairs officer, Foster was not quite prepared for the welcome he received.

Roughly 25 fellow motorcycle enthusiasts met Foster at the gate to provide an escort onto post in a roaring cavalcade festooned with American flags. Coincidentally, British troops were training and Foster recognized his fellow countrymen as the escort rolled past a convoy on maneuvers.

Command Sgt. Maj. Andre S. Machado, Joint Multinational Readiness Center "Vampire" team, one of the riders participating in the motorcycle escort, said he was fascinated when he learned of Foster's quest to track his father's war experience.

"As a 25-year Soldier, you don't get stuff like this every day," he said. "We're in a place where we get a lot of great stuff, but this is probably the highlight of my year."

Foster shared his story with the gathered Soldiers and passed around a collection of old photos of his father's POW days. With Wittl's help, they were able to line up landmarks and ascertain the exact position of various structures in the photos, none of which remain today.

"It feels surreal to know that my father may have stood right over there," Foster said.

"It all comes to life when you hear these stories and then you're walking in the footsteps of someone who was here 73 years ago," said Chris.

Foster fought back his emotions as he stood near the crumbled foundations of an old guard shack overlooking the camp where his father spent two and a half years.

"It's a journey through his life I've taken," he said. "This is a way I can find out exactly what he did and where he stood. It's highly emotional, but it has been a very worthwhile journey, and this is the last part."

Col. John G. Norris, JMRC commander, said Foster's visit and his efforts to walk in the footsteps of his father helps to highlight Hohenfels' connection with history and communicates another reason why JMRC is a significant place to train.

After visiting Hohenfels, Foster set off on the last leg of his journey, tracing the final phase of his father's escape through Munich and into Lindau.

"I want to try and find the Gestapo headquarters in Lindau where they were interrogated," he said.

Everything Foster has learned, he has documented and catalogued, sharing his discoveries not only with his own family, but as part of the syllabus covering POWs for the British Military Intelligence Corps where he speaks three times a year.

Though Foster wishes he'd questioned his father more while he was alive, he is grateful for this opportunity to learn more about the man and the chapter of his life that he kept so silent about.

"I think he talked more about his action in Norway, which lasted five days, and he was a POW for five years," Foster said. "But it adds to the mystique, I think, finding it out from letters, building up this story from paper."

"Each step you make really whets the appetite to try and find out a little more information, and see what the next step is," Chris agreed. "I think it's sad that (Sgt. Foster) isn't here to see what Steve's done, because I think he'd be extremely proud of him."

One of Foster's most significant discoveries was locating the grave of Coulthard, who died on 'the long march,' when over 80,000 POWs were forced to march westward across Poland, then-Czechoslovakia, and Germany in extreme winter conditions, over about four months between January and April 1945.

After nearly a year of research and countless letters to dozens of agencies, Foster gathered enough evidence to present his findings to the Commonwealth War Grave Commission.

Currently under review by the British Ministry of Defense, Foster expects the previously "unknown" grave to be renamed.

"At that point, Antony Coulthard's regiment will provide a color guard at the ceremony," said Foster. "I'll put my uniform back on for that, to salute the man."

With his journey nearing its end, Foster realizes the lessons he's learned need to be shared.

"We probably never tell (our fathers) enough how much we love them," he said. "I didn't ask enough questions. My advice to all young Soldiers is take your father, your grandfather, aside and ask before it's too late."

Social Sharing